by James Wallace Harris, 5/2/25

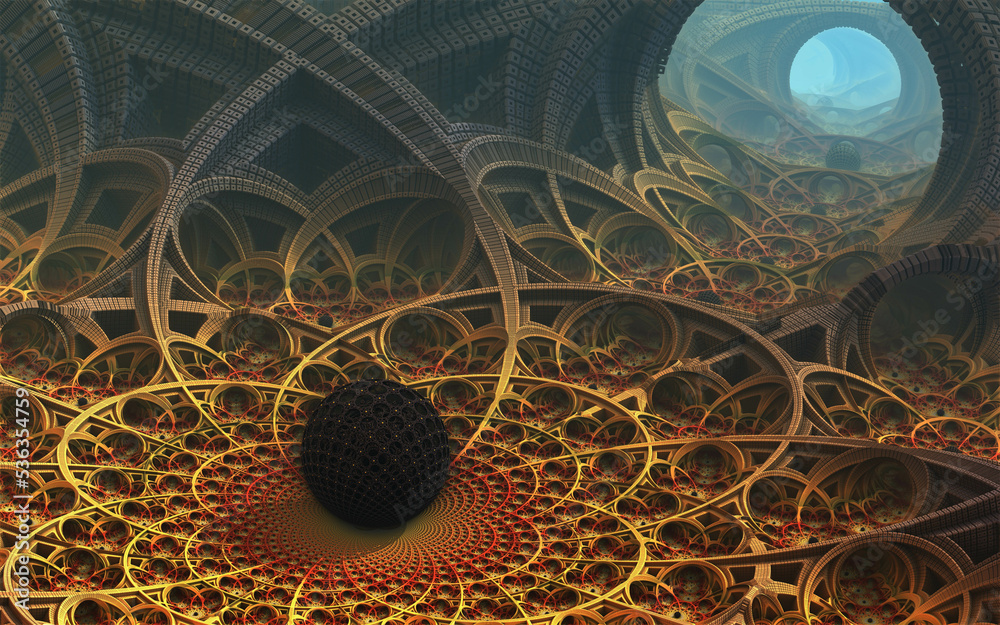

I use reality to mean everything in existence. We used to use the term universe to mean everything, but scientists began speculating about multiverses and the word universe meant less than everything. Also, we tend to think of the universe in astronomical terms, and when I mean everything, I want it to encompass all the dimensions of existence everywhere, to whatever is beyond the quantum world to whatever existences lies beyond the multiverses.

The first reality of reality is that our local existence is an infinitely tiny portion of reality. We appear to exist in a three-dimensional domain defined by our sight, which gives us the illusion that we are small creatures in a large world. In reality, we are specks on a speck.

The second thing we need to remember about reality is that our lives have no meaning in relation to reality. Reality is completely indifferent to our existence. That every religion and philosophy we’ve ever created to explain reality are delusions by infinitesimally tiny beings. Think of our thoughts as a bacterium in our body speculating about its existence.

The third thing to remember about reality is that we spend our entire existence imposing order on chaos in our local bit of reality. Subatomic particles create atoms, and atoms create molecules, and molecules create inorganic chemistry, and inorganic chemistry creates biology, and biology creates humans, and humans create civilizations, and civilizations create technology, and technology is creating artificial intelligence. Reality is always evolving into something else.

Everything we do involves creating order out of chaos. We breathe and eat to stay alive. We learn to make sense of reality. We work to own things. We maintain the things we own. Doing the dishes imposes order on the kitchen. Washing clothes imposes order on our wardrobes. Gardening and landscaping impose order on our yard. Writing imposes order on our thoughts. Decluttering imposes order on our desks. Talking to people creates order in our relationships.

How much order we impose depends on how many habits, possessions, and people we want to control. The more we try to control, the more stress we feel. As we age, and our physical and mental abilities decline, we slowly lose control of everything we’ve worked to control. That is the reality of our lives.

We comprehend reality through science, but it’s extremely difficult because reality is hard to understand. At best, science notices repeatable statistical patterns that we can label with terms that we share. Like I said, religions and philosophies are mere delusions we embrace to think we understand reality. We don’t. We spend our lives acting on beliefs, believing we know more than we do.

We are creatures who live on delusions imposed on us by our biological urges and the delusions imposed on us by our culture and society. Except for Zen Buddhists, few people attempt to free themselves of their delusions. Instead, they passionately embrace their delusional beliefs by expending vast efforts to make them a reality.

I think about all of this as I encourage myself to go outside this morning to work at imposing order on the forty-thousand square feet of chaos that is my yard. The weeds are winning. They want to impose their order over my plot of land that I delusionally think I own and control. But it looks like rain, and as I glance around this room, I see three desks piled high with disorder that I need to wrestle into order. And I haven’t done my physical therapy exercises yet. If I don’t do them, my back falls into chaos, and I suffer great pain.

It would be so much easier to veg out in front of YouTube videos and let a little more disorder take over the house and yard.

JWH