by James Wallace Harris, 12/27/25

There are some conservative Republicans who wish to censor history by forgetting events in America’s past. They worry that such history could make their children feel bad about themselves. They want to remember a past that makes America look great again. Please read Donald Trump’s executive order regarding this issue.

Karen Russell’s latest novel, The Antidote, philosophises why we need to remember everything, even things our ancestors did that make America look bad. Russell uses fantasy to educate us about reality. When my friend Annie first recommended that we read this novel together, the fantasy elements turned me off. As a life-long science fiction reader, I was in the mood to read realistic fiction for a change. The older I get, the more I want nonfiction, but I can’t give up fiction completely.

Throughout the first half of The Antidote, I was annoyed with all its fantastic elements. However, I eventually realized that Russell was using them as a plot device to get her readers to contemplate real history. Eventually, I felt Russell had read a great deal of American history that disturbed her, and she was using her novel to come to grips with why we shouldn’t forget that which many want to erase from American history books.

Memory is the main theme of this novel. Both personal memories and historical memory.

The Antidote makes a case against five crimes our ancestors committed. These tragic deeds explore the dimensions of greed. Each of these historical atrocities has been well-documented in nonfiction books I’ve read over the years. Reading the novel made me ask: Which has more impact, fiction or nonfiction? Listening to The Antidote made me feel closer to the suffering.

How many books have you read that deal with these historical events? Did you learn more from reading fiction or nonfiction?

- How did we take land from the Native Americans?

- How did we force Native Americans onto reservations and attempt to reeducate them with our culture and values?

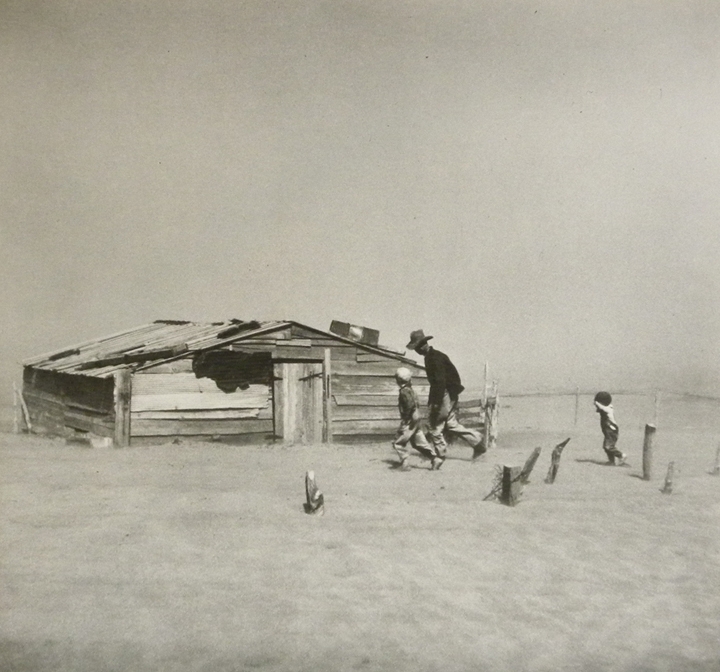

- How did poor farming practices cause the environmental catastrophe of the Dust Bowl?

- How did we institutionalize unwed mothers and steal their babies?

- How do we allow the murders of women to go uninvestigated and underreported?

The Antidote is primarily set in the fictional town of Uz, Nebraska, in 1935, between two significant real events, the Black Sunday dust storm (April 14, 1935) and the Republican River flood (May 31-June 1, 1935). The story is told sequentially, but with flashbacks. We hear the story told from many voices. Four primary characters: The Antidote (Antonina Rossi, AKA, the Prairie Witch), Asphodel Oletsky (Del), Harp Oletsky (Del’s uncle), and Cleo Allfrey (photographer), along with two significant secondary characters, a cat and a scarecrow.

Antonina, a middle-aged woman, had been institutionalized at age 15 for being an unwed mother. Her son had been forcefully taken away from her. She makes her living as a vault, or prairie witch. Antonina can enter a trance while another person relates a memory they wish to forget. That process will erase the memory from the teller’s mind and store it in hers. Antonina gives them a written receipt that will trigger that memory, and she can reinstate it at a future time. Antonina does not remember what she vaults. She is paid for this service, but her clients consider her no better than a prostitute.

Asphodel “Del” Oletsky, a fifteen-year-old girl, just five feet tall, is the captain of Uz’s high school girls’ basketball team. Her mother was murdered when she was young, and she lives with her uncle Harp Oletsky. Cleo is a young black woman who travels the country documenting the depression for FDR’s government. The plot of the novel eventually brings them all together.

The novel begins with a roundup of jack rabbits and clubbing them to death. My father was born in Nebraska and was Del’s age in 1935. He told me stories about how the farmers would exterminate the jack rabbits. My mother also went to high school around this time and played basketball. My grandmother was on a basketball team in Indiana at the turn of the century.

My memories immediately made me connect with the story. We remember the good ones, but forget the bad ones.

The story then goes into catching a serial killer of young women. The sheriff even connects the killer to Del’s mother’s cold case. This murder mystery is the apparent backbone of the plot, but it’s not the real story.

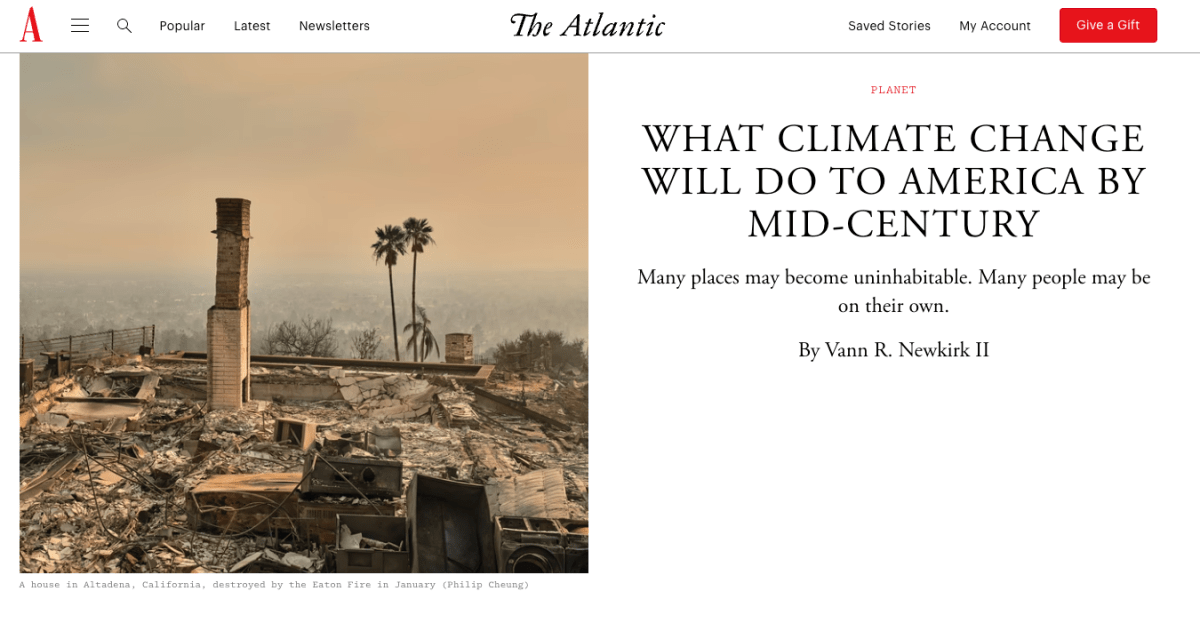

The Antidote immediately triggered a memory of an article I recently read, “The Nurse Who Names the Dead” by Christa Hillstrom. The article was about Dawn Wilcox, who created a database to track the number of men killing women. She discovered that femicide goes vastly underreported. One of the truths of Russell’s novel is that she’s writing about evils that have always existed. Can we ever break the cycle?

Dust and evil color this novel with darkness. I listened to the audiobook edition, and it felt like I was watching an old black-and-white movie. I’d call it noir magical realism.

I admit, I had to push myself to keep listening for the first half of this book. I was just put off by the fantasy elements. But the characters grew on me. And by the middle of the story, I was hooked. The last half of the book often made me teary-eyed. For most of the novel, I felt Russell was too writerly, but when Harp gives his big speech near the end, I must say I was quite impressed with the writing and the description of the riot and storm.

Throughout this story, I kept thinking about the Oz books by L. Frank Baum. Uz almost sounds like Oz. Plus, the story has a tornado and a talking scarecrow.

I wanted to connect the elements of this story with all the nonfiction books I’ve read that back up its fictional history. Especially, The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl by Timothy Egan, plus the Ken Burns’ documentary, The Dust Bowl. However, I can’t remember where I read about the other issues in this book. My mind is getting old and tired.

My friend Linda and I often talk about how humans repeat the same crimes throughout history. In recent months, we’ve focused on how greed is the primary driver of evil. As you read The Antidote (if you do), think about how greed motivates people to do what they do. We’re all greedy to a degree, and that might be a survival mechanism, but there seems to be a point when more greed makes us evil. I see that everywhere.

I’m also watching The American Revolution by Ken Burns. It brings up many things that some Republicans would like the world to forget. Like I said, we don’t change. But we should ask, what are we doing now that people in the future will wish to forget that we did?

The Antidote by Karen Russell was on 11 best-books-of-the-year lists for 2025.

JWH