by James Wallace Harris, 12/12/25

I’ve been contemplating how robot minds could succeed at explaining reality if they didn’t suffer the errors and hallucinations that current AIs do. Current AI minds evolve from training on massive amounts of words and images created by humans stored as digital files. Computer programs can’t tell fiction from fact based on our language. It’s no wonder they hallucinate. And like humans, they feel they must always have an answer, even if it’s wrong.

What if robots were trained on what they see with their own senses without using human language? Would robots develop their own language that described reality with greater accuracy than humans do with our languages?

Animals interact successfully with reality without language. But we doubt they are sentient in the way we are. But just how good is our awareness of reality if we constantly distort it with hallucinations and delusions? What if robots could develop consciousness that is more accurately self-aware of reality?

Even though we feel like a being inside a body, peering out at reality with five senses, we know that’s not true. Our senses recreate a model of reality that we experience. We enhance that experience with language. However, language is the source of all our delusions and hallucinations.

The primary illusion we all experience is time. We think there is a past, present, and future. There is only now. We remember what was, and imagine what will be, but we do that with language. Unfortunately, language is limited, misleading, and confusing.

Take, for instance, events in the New Testament. Thousands, if not millions, of books have been written on specific events that happened over two thousand years ago. It’s endless speculation trying to describe what happened in a now that no longer exists. Even describing an event that occurred just one year ago is impossible to recreate in words. Yet, we never stop trying.

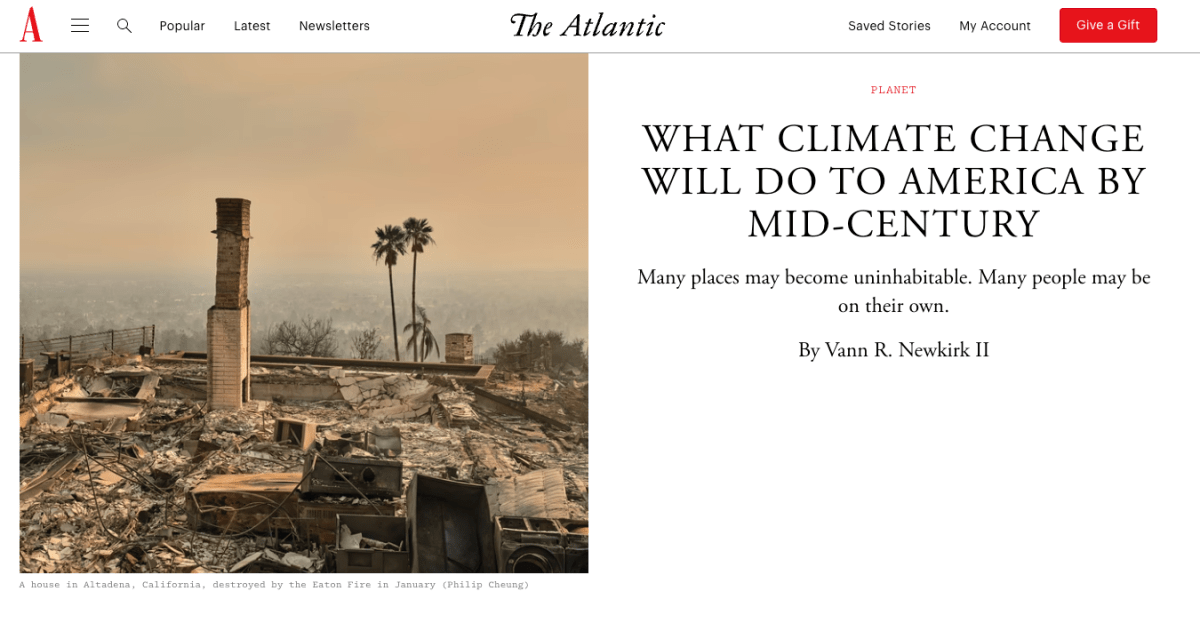

To compound our delusions is fiction. We love fiction. Most of us spend hours a day consuming fiction—novels, television shows, movies, video games, plays, comics, songs, poetry, manga, fake news, lies, etc. Often, fiction is about recreating past events. Because we can’t accurately describe the past, we constantly create new hallucinations about it.

Then there is fantasy and science fiction. More and more, we love to create stories based on imagination and speculation. Fantasy exists outside of time and space, while science fiction attempts to imagine what the future might be like based on extrapolation and speculation.

My guess is that any robot (or being) that perceives reality without delusions will not use language and have a very different concept of time. Is that even possible? We know animals succeed at this, but we doubt how conscious they are of reality.

Because robots will have senses that take in digital data, they could use playback to replace language. Instead of one robot communicating to another robot, “I saw a rabbit,” they could just transmit a recording of what they saw. Like humans, robots will have to model reality in their heads. Their umwelt will create a sensorium they interact with. Their perception of now, like ours, will be slightly delayed.

However, they could recreate the past by playing a recording that filled their sensorium with old data recordings. The conscious experience would be indistinguishable from using current data. And if they wanted, they could generate data that speculated on the future.

Evidently, all beings, biological or cybernetic, must experience reality as a recreation in their minds. In other words, no entity sees reality directly. We all interact with it in a recreation.

Looking at things this way makes me wonder about consuming fiction. We’re already two layers deep in artificial reality. The first is our sensorium/umwelt, which we feel is reality. And the second is language, which we think explains reality, but doesn’t. Fiction just adds another layer of delusion. Mimetic fiction tries to describe reality, but fantasy and science fiction add yet another layer of delusion.

Humans who practice Zen Buddhism try to tune out all the illusions. However, they talk about a higher state of consciousness called enlightenment. Is that just looking at reality without delusion, or is it a new way of perceiving reality?

Humans claim we are the crown of creation because our minds elevate us over the animals, but is intelligence or consciousness really superior?

We apparently exist in a reality that is constantly evolving. Will consciousness be something reality tries and then abandons? Will robots with artificial intelligence become the next stage in this evolutionary process?

If we’re a failure, why copy us? Shouldn’t we build robots that are superior to us? Right now, AI is created by modeling the processes of our brains. Maybe we should rethink that. But if we build robots that have a higher state of consciousness, couldn’t we also reengineer our brains and create Human Mind 2.0?

What would that involve? We’d have to overcome the limitations of language. We’d also have to find ways to eliminate delusions and hallucinations. Can we consciously choose to do those things?

JWH