by James Wallace Harris, 8/14/25

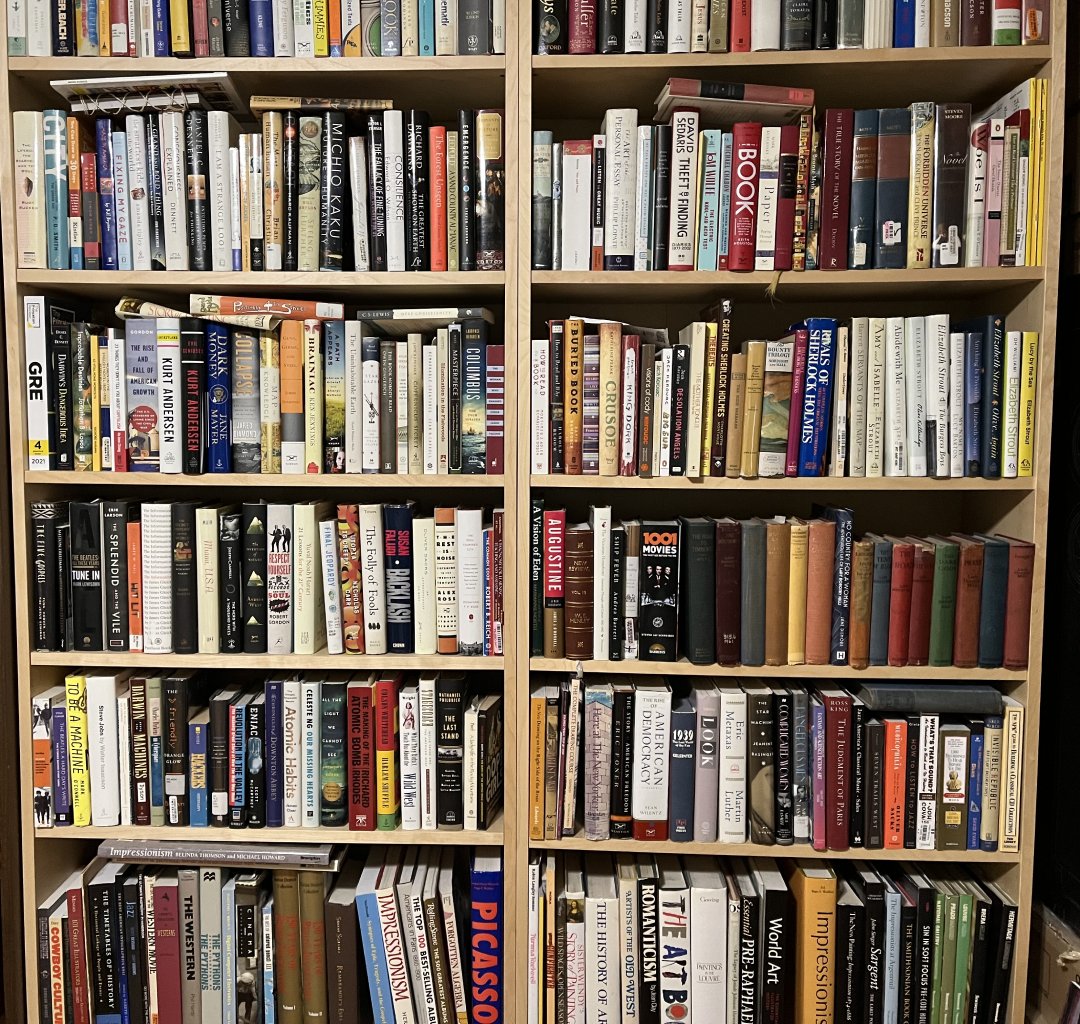

I bought more than a thousand books, preparing for retirement, thinking that after I left the nine-to-five grind, I’d have all the time in the world to read them. It’s not working out like I planned. All the time in the world has turned out to be much less than I imagined. Old age does a number on your temporal sense, which I didn’t anticipate. Being retired turns off the “gotta do this soon” mechanism in the brain, so it’s much easier to tell myself I’ll get around to that someday.

I’ve always wanted a catchy saying about buying more books than I can read, that parallels that old idiom about eating, “My eyes were bigger than my stomach.” My ability to acquire books far exceeds my ability to read them.

This problem is mainly due to my inability to commit. Learning is about specializing. To go deep into any subject requires ignoring all other subjects. I’m as indecisive as Hamlet when it comes to picking a project and sticking with it. However, I feel like I’m zeroing in on something. I don’t know what. I’d like to write a book. I have several ideas. I just can’t commit to one.

Looking through my books, I see that I’m torn between understanding the past, working in the present, and anticipating the future. The momentum of aging makes me retrospective, but I need to fight that. The present is real, and the past and future aren’t. However, to survive well in the present requires some knowledge of the past. And since we always act in the moment, we still feel we’re preparing for the future.

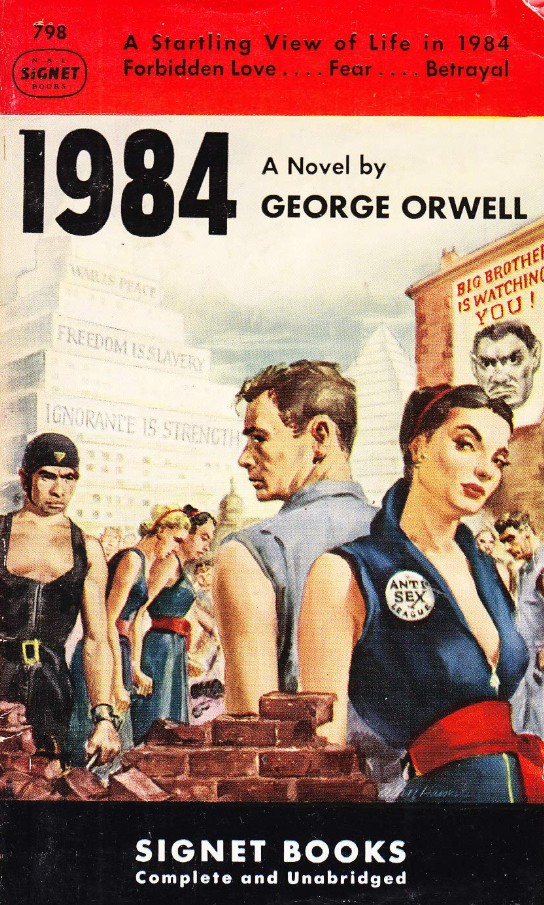

The Lesson of Destination Moon

Destination Moon was a 1950 science fiction film about the first manned rocket to the Moon. It was loosely based on Robert A. Heinlein’s Rocket Ship Galileo, and Heinlein contributed to the screenplay. In the story, the astronauts use too much fuel when landing on the Moon. To have enough fuel to take off and return to Earth, the astronauts must reduce the weight of the rocket and its contents. They throw everything they can out of their rocket ship, including the radio, equipment, seats, and their space suits. With the reduced weight, they take off for Earth.

In old age, I have too many goals, desires, and possessions holding me down. Their weight keeps me from accomplishing any larger goal. I need to jettison everything I can. I’m starting by evaluating my book collection and tallying all the subjects I want to study and read about.

This will be a multi-stage process. In this essay, I’m looking at all my books and listing the subjects I thought I wanted to study. Here is the current list, and even though it’s long, it’s still partial:

- 1939 World Fair

- 1960s

- 1960s Counter Culture

- Aging

- Alexander von Humboldt

- Alfred Hitchcock

- American History

- American Literature

- Amor Towles – Writer

- Anthony Powell – Writer

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Art history

- Artificial Intelligence

- Astronomy

- Bible Archaeology

- Bible History

- Biographies

- Bob Dylan

- Books – History

- Boston – 19th Century History

- British Literature

- British Literature Between the Wars

- Charles Darwin

- Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall – Writers

- Chess

- Classical Music

- Classical Studies

- Climate Change

- Computer History

- Computers

- Country Music

- Creative Fiction

- Creative Nonfiction

- Databases

- Democracy

- Drawing

- Early Christianity

- Economics

- Electronics – Learning

- Elizabeth Strout – Writer

- Environmentalism

- Ernest Hemingway – Writer

- Feminism

- Feminist History

- Fiction

- Future

- Gerontology

- Go Programming

- H. G. Wells

- Hollywood vs. History

- Impressionism

- Information and Information Theory

- Information Hierarchy

- Jack Kerouac – Writer

- Jazz

- Lady Dorothy Mills – Writer

- Learning – Study Methods

- Linux / Unix

- Literary History

- Literature

- MacOS

- Magazines – History

- Mark Twain

- Mathematics – History

- Mathematics – Pure

- Memory

- Miami – History

- Mitford Sisters

- Movies – History

- Music – History

- Nassim Nicholas Taleb – Writer

- Network Attached Storage (NAS)

- Nostalgia

- Note Taking Systems

- Obsidian – Software

- Old West

- Particle Physics

- Philip K. Dick – Writer

- Philosophy

- Photography – History

- Photography – How To

- Politics

- Power Grid

- Pulp Magazines

- Python Programming

- Quantum Mechanics

- Reading

- Renewable Energy

- Rhetoric

- Robert A. Heinlein – Writer

- Rock Music

- Scanning – Books and Magazines

- Science

- Science – History

- Science Fiction

- Science Fiction – Criticism

- Science Fiction – History

- Science Fiction – Magazines

- Short Stories

- Sustainability

- Taxonomy

- Technology

- Television – History

- The Beats

- The Lost Generation

- Westerns – Books

- Westerns – Movies

- Westerns – Television Shows

- Windows – OS

- Writing

- Yuval Noah Harari – Writer

One of the first decisions I made was to give up on westerns. I have collected many westerns on DVDs. Along the way, I started collecting books on movie and TV westerns. I decided that in the remaining years of my life, I didn’t need to know that much about Westerns. I also gave away my books on TV history.

I’m approaching each subject like I did with Westerns.

Another example, while flipping through my math books, I decided to abandon any hope of relearning math. I gave away my books on pure math. However, I kept books on the history of math. I still want to see the big picture of history. In the long run, I might have to abandon any interest in math. I just don’t know at the moment. This is a process.

Do I Keep Books I’ve Already Read?

I’ve always kept books I’ve read as a form of external memory. The painful truth is, I seldom consult those books. I’ve long known it’s cheaper to buy books at full price when I need them rather than to stockpile them when I find them as bargain used books or Kindle deals. I think the same thing might apply to keeping books. The time and energy that goes into maintaining them in my library is more expensive than just rebuying a book if I want to reread it.

For example, I gave all my Elizabeth Strout books to my friend Ann. If I ever want to reread them, I’ll try the library.

Whatever Happened to Libraries?

It used to be that libraries were depositories of knowledge. I don’t feel that anymore. I’ve gone to the public library too many times to research a subject only to find a battered collection of old books. That’s why I’ve bought my own. However, I don’t think it’s practical to be my own public library.

We can find massive collections of information on the Internet or with AIs. Unfortunately, I don’t trust those sources.

I wish I had a trusted source of online knowledge.

Kindle and Audible Books

I’m not worrying about my digital books because they are out of sight, and thus out of mind.

I decided to get rid of any physical fiction books that I had on Kindle, but not if I owned them on Audible. I like seeing the words. For now, I’ll keep the physical copies of nonfiction books if I also own them as an ebook. I prefer flipping through the pages of a book when studying.

The Limits of Memory

There are many books I’ve kept because I hoped to study a subject. For instance, I’ve long fantasized about relearning mathematics. I got through Calculus I in college, but then I waited too long to take Calculus II. This is why I gave away my pure math books. I can no longer remember things well enough to study a complex subject.

Whatever books I choose to read in this last part of my life, they need to be books that expand my overall impression of reality, but don’t require me to remember the details.

I guess I’m going for wisdom over data.

Limits of Time

I’m hesitant to keep my art history books. I enjoy looking at the pictures, but I just don’t have time to study many more subjects in this lifetime. My interests include several subjects that could become a black hole of study. I really should flee from them.

I’m trying to decide my “Major” for old age. All my life, I’ve been a knowledge grazer. I nibble at one subject and then move on to another. I’ve always wanted to go deep into one area, to specialize. However, I never could settle down. I’m probably too old to change my ways now. I’m going to try, though. The process of selecting my major will be the topic of the next essay.

Shrinking My Library to Focus My Mind

I gave the library a lot of books today. I love buying books. I love owning books. But I own too many for this time of my life. I also have too many things I’m interested in. Too many for the time and energy I have at age 73. I’m like the rocket in Destination Moon. I’m too heavy for the fuel in my tanks.

It would help if I had a committed destination. I’d know what to keep and what to jettison.

JWH