by James Wallace Harris, 11/16/25

While listening to the Radio Atlantic podcast, “What If AI Is a Bubble?,” a conversation between host Hanna Rosin and guest Charlie Warzel, I kept thinking I had heard this information before. I checked and found that I had read “Here’s How the AI Crash Happens” by Matteo Wong and Charlie Warzel, which Rosin had mentioned in her introduction.

Over the past year, I’ve been paying attention to how podcasts differ from long-form journalism. I’ve become disappointed with talking heads. I know podcasts are popular now, and I can understand their appeal. But I no longer have the patience for long chats, especially ones that spend too much time not covering the topic. All too often, podcasts take up excessive time for the amount of real information they cover.

What I’ve noticed is that the information density between podcasts and long-form journalism is very different. Here’s a quote, five paragraphs from the podcast:

Warzel: There’s a recent McKinsey report that’s been sort of passed around in these spheres where people are talking about this that said 80 percent of the companies they surveyed that were using AI discovered that the technology had no real—they said “significant”—impact on their bottom line, right?

So there’s this notion that these tools are not yet, at least as they exist now, as transformative as people are saying—and especially as transformative for productivity and efficiency and the stuff that leads to higher revenues. But there’s also these other reasons.

The AI boom, in a lot of ways, is a data-center boom. For this technology to grow, for it to get more powerful, for it to serve people better, it needs to have these data centers, which help the large language models process faster, which help them train better. And these data centers are these big warehouses that have to be built, right? There’s tons of square footage. They take a lot of electricity to run.

But one of the problems is with this is it’s incredibly money-intensive to build these, right? They’re spending tons of money to build out these data centers. So there’s this notion that there’s never enough, right? We’re going to need to keep building data centers. We’re going to need to increase the amount of power, right? And so what you have, basically, is this really interesting infrastructure problem, on top of what we’re thinking of as a technological problem.

And that’s a bit of the reason why people are concerned about the bubble, because it’s not just like we need a bunch of smart people in a room to push the boundaries of this technology, or we need to put a lot of money into software development. This is almost like reverse terraforming the Earth. We need to blanket the Earth in these data centers in order to make this go.

Contrast that with the opening five paragraphs of the article:

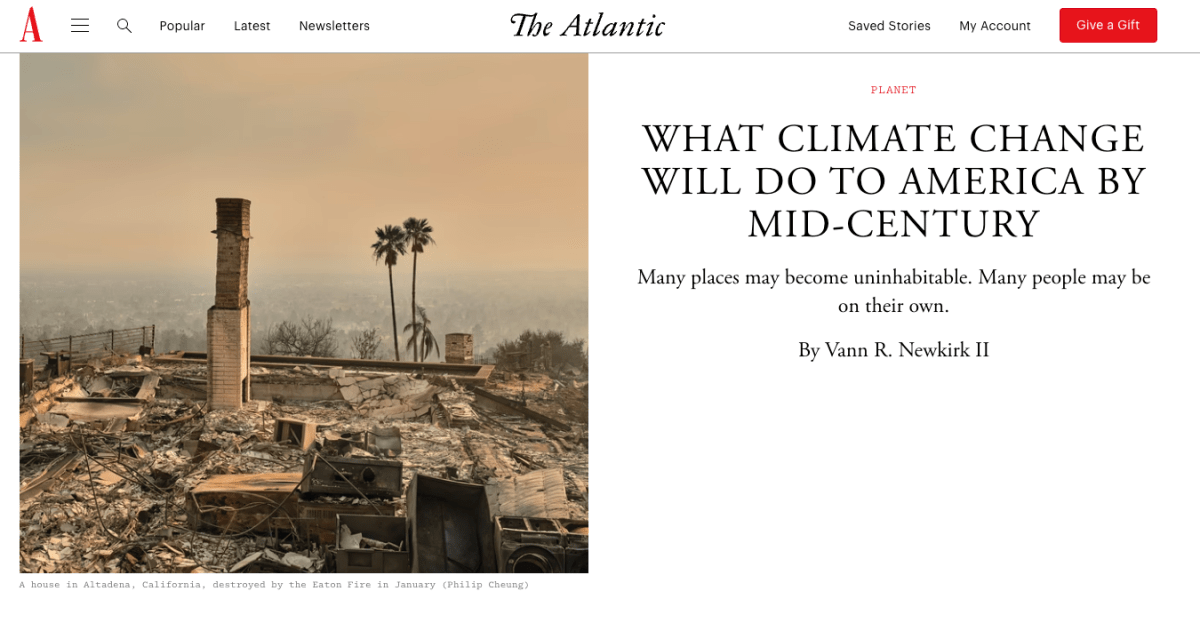

The AI boom is visible from orbit. Satellite photos of New Carlisle, Indiana, show greenish splotches of farmland transformed into unmistakable industrial parks in less than a year’s time. There are seven rectangular data centers there, with 23 more on the way.

Inside each of these buildings, endless rows of fridge-size containers of computer chips wheeze and grunt as they perform mathematical operations at an unfathomable scale. The buildings belong to Amazon and are being used by Anthropic, a leading AI firm, to train and run its models. According to one estimate, this data-center campus, far from complete, already demands more than 500 megawatts of electricity to power these calculations—as much as hundreds of thousands of American homes. When all the data centers in New Carlisle are built, they will demand more power than two Atlantas.

The amount of energy and money being poured into AI is breathtaking. Global spending on the technology is projected to hit $375 billion by the end of the year and half a trillion dollars in 2026. Three-quarters of gains in the S&P 500 since the launch of ChatGPT came from AI-related stocks; the value of every publicly traded company has, in a sense, been buoyed by an AI-driven bull market. To cement the point, Nvidia, a maker of the advanced computer chips underlying the AI boom, yesterday became the first company in history to be worth $5 trillion.

Here’s another way of thinking about the transformation under way: Multiplying Ford’s current market cap 94 times over wouldn’t quite get you to Nvidia’s. Yet 20 years ago, Ford was worth nearly triple what Nvidia was. Much like how Saudi Arabia is a petrostate, the U.S. is a burgeoning AI state—and, in particular, an Nvidia-state. The number keeps going up, which has a buoying effect on markets that is, in the short term, good. But every good earnings report further entrenches Nvidia as a precariously placed, load-bearing piece of the global economy.

America appears to be, at the moment, in a sort of benevolent hostage situation. AI-related spending now contributes more to the nation’s GDP growth than all consumer spending combined, and by another calculation, those AI expenditures accounted for 92 percent of GDP growth during the first half of 2025. Since the launch of ChatGPT, in late 2022, the tech industry has gone from making up 22 percent of the value in the S&P 500 to roughly one-third. Just yesterday, Meta, Microsoft, and Alphabet all reported substantial quarterly-revenue growth, and Reuters reported that OpenAI is planning to go public perhaps as soon as next year at a value of up to $1 trillion—which would be one of the largest IPOs in history. (An OpenAI spokesperson told Reuters, “An IPO is not our focus, so we could not possibly have set a date”; OpenAI and The Atlantic have a corporate partnership.)

Admittedly, the paragraphs in the article are somewhat longer, but judge them on the amount of facts each presents.

Some people might say podcasts are more convenient. But I listened to the article. I’ve been subscribing to Apple News+ for a while now. I really didn’t use it daily until I discovered the audio feature. And it didn’t become significant until I began hearing major articles from The New Yorker, The Atlantic, and New York Magazine.

Whenever I listened to a podcast, including podcasts from those magazines, I was generally disappointed with their impact. Conversational speech just can’t compete with the rich informational density of a well-written essay. And once I got used to long-form journalism, the information I got from the internet and television seemed so damn insubstantial.

These magazines have spoiled me. I’m even disappointed with their short-form content. Over my lifetime, I’ve watched magazines fill their pages with shorter and shorter content. Interesting tidbits came to magazines long before the internet appealed to our ever-shortening attention spans.

As an experiment, I ask you to start paying attention to the length of the content you consume. Analyze the information density of what you read, either with your eyes or ears. Pay attention to the words that have the greatest impact. Notice what percentage of a piece is opinion and what percentage is reported facts. How are the facts presented? Is a source given? And when you look back, either from a day or a week, how much do you remember?

What do you think when you read or hear:

According to one estimate, this data-center campus, far from complete, already demands more than 500 megawatts of electricity to power these calculations—as much as hundreds of thousands of American homes. When all the data centers in New Carlisle are built, they will demand more power than two Atlantas.

Don’t you want to know more? Where did those facts come from? Are they accurate? Another measure of content is whether it makes you want to know more. The article above drove my curiosity to insane levels. That’s when I found this YouTube video. Seeing is believing. But judging videos is another issue, but that’s for another time.

JWH