by James Wallace Harris, 4/12/25

Stone Yard Devotional is about how reality puts the peddle to the metal when life gets all too real. Stone Yard Devotional reads like a memoir, a diary, but it’s classified as a novel. The book was nominated for several awards.

The entire time I was listening to this book I wondered if Charlotte Wood was the unnamed narrator, however after reading “‘The shock was so deep’: Novelist Charlotte Wood on the experience that changed everything” in the Syndney Herald, I realized the novel was only inspired by her own life. Wood and her two sisters were being treated for breast cancer, while she was contemplating mortality and drafting this book.

I have no memory of how I discovered Stone Yard Devotional by Charlotte Wood. The cover and title intrigued me for sure. Maybe it was because it was shortlisted for the 2024 Booker Prize. The audiobook was part of my Spotify subscription, so I gave it a try, and I’m glad I did. It’s not the kind of book I normally read, but it’s wonderful to read if you’re getting old.

The story begins with the Covid pandemic. The narrator separates from her husband, ghosts her friends, and hides out in a guest house of a religious order, even though she is nonreligious. She wants to be alone. But after her initial stay, she returns to the order to live with the nuns. I was never sure if she joined the order or not. I have often thought the monastic life has certain appeals.

The story is about the narrator’s observations while living a contemplative life. These include the death of her mother, the remembrance of childhood, studying the nuns, working in the garden and kitchen, and the guilt of living with a woman she and her classmates horribly bullied as a child. The narrative is simple, like meditation.

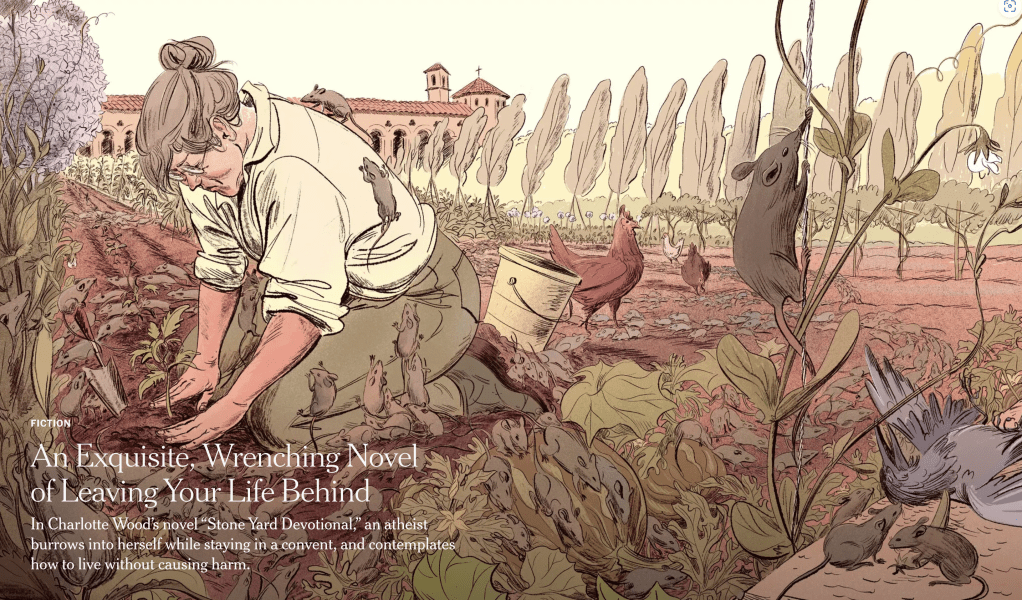

The setting is Australia, which is exotic to me. As a kid I wanted to live in Australia. Over the course of the novel, there is a plague of mice that invade the convent. The mice are so numerous that they cover the roads in gray fur. At first, I thought Wood added this element to give her tale some excitement, but I researched and found that her part of Australia they did have a mice plague of Biblical proportions in 2021.

That made life in the convent extremely inconvenient. The mice ate electrical insulation, throwing daily living in the convent back to the 19th century. The illustration for the book’s review at The New York Times might have been another reason I read this book.

Much of what the unnamed narrator contemplates throughout the novel is what everyone thinks about as they get older. The fear of declining health and death, the regrets, the desires for wanting to have done things different, the desires to connect with others while also wanting to pull away, the changes we see in ourselves and others, the appeal of nature and living simple. Wood’s story explores all of that and more, triggering the reader to think about their lives.

Charlotte Wood was born in 1965, so she’s fourteen years younger than me. However, her battle with cancer has likely aged her perception on life. At 73, I’ve been thinking about the things in this novel for years. But I don’t know if everyone who collects social security meditates on these issues. Stone Yard Devotional is a great title for this novel. Even though the narrator said she was an atheist at the beginning of this story, getting old and dealing with people who die, pushes you to be spiritual even without a belief in God.

- Quotes about the book at the author’s home page

- Interview with author at NPR

- Information about the book at the Booker Prize website

JWH