by James Wallace Harris, 11/22/24

I used the Grammarly browser extension for years. It offered spelling and basic grammar advice whenever I wrote anything within a browser window. About a year ago I switched from Chrome to Edge, and Edge had an extension, Editor, built in, so I deleted Grammarly. However, recently when Edge’s Editor stopped working, I turned Grammarly back on.

I discovered that Grammarly was now offering a lot more advice, even suggesting rewrites for whole sections of my work. Each time I loaded the browser, Grammarly would offer a couple of free major writing suggestions hoping I would switch to the paid version. I was tempted, but the Pro version is $30 a month, or $144 if bought yearly. This seems extremely expensive since Office 365 costs me $69 a year and gives me Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Publisher, Access, and other programs along with one terabyte of cloud storage for that one low yearly price. For a simple web extension like Grammarly, I’d only be willing to pay no more than $29 a year.

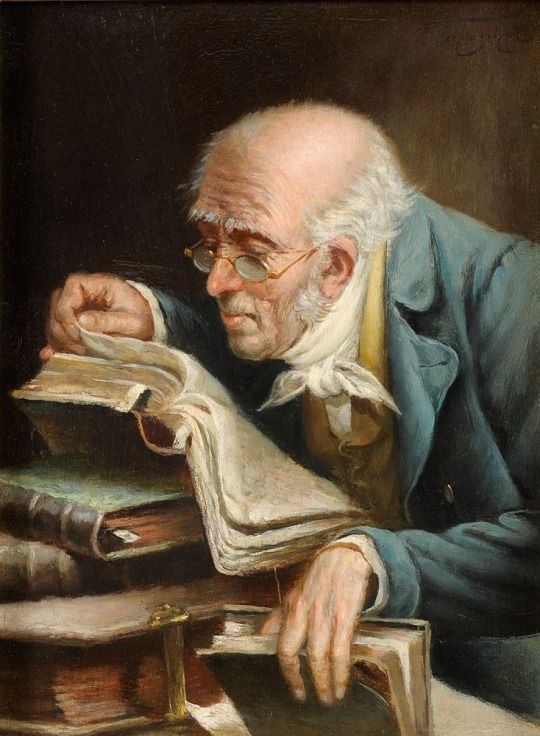

However, for $144 a year, Grammarly promises to make my writing perfect. But then, who would be authoring my essays? Would I become a literary cyborg? I would still be generating the ideas for the essays, and I would be writing the original draft, but somewhere along the way, an AI would be taking over. I’m not sure I like that. The reason why I write these essays is to exercise my mind. Letting an AI do all the work would turn my writing muscles into flab.

I have found a way to use the free Grammarly to my advantage. After a couple of sample offers to rewrite my work, Grammarly nags the heck out of me with suggested changes that’s been redacted with fuzziness so I can’t see what they are suggesting. Grammarly wants me to buy the Pro version, and so they criticize almost everything I write. What I do is keep rewriting the prose myself until the AI stops offering suggestions. This pushes me to think about how I’m saying something.

Instead of letting the Grammarly AI rewrite for me, I take the free nagging as “This isn’t good enough – try again!” The free Grammarly extension has become my Zen master, caning my about the head and shoulders whenever I write poorly.

Now some bloggers are using AI programs to write their content. I don’t plan to do this, but to see how well AIs write, I asked CoPilot to write me a short essay about how Grammarly makes me a cyborg writer. Here’s what it produced:

Grammarly: The Cyborg Writer's Best Friend

In the age of digital communication, tools like Grammarly have become indispensable for writers, students, and professionals alike. But beyond just correcting grammar and spelling, Grammarly is transforming the way we write, making us more efficient, precise, and, in a sense, more like cyborgs.

Enhanced Writing Efficiency

Grammarly's real-time suggestions streamline the writing process. Instead of laboriously proofreading and editing, writers can focus on their ideas and creativity. Grammarly catches errors on the fly, allowing for a smoother and faster writing experience. This efficiency is akin to having a digital co-writer, enhancing our natural abilities with the precision of artificial intelligence.

Precision and Clarity

Grammarly doesn't just correct mistakes; it also improves the clarity and impact of our writing. By suggesting better word choices, sentence structures, and even tone adjustments, Grammarly ensures that our messages are not only error-free but also compelling and effective. This level of precision is something that even the most seasoned writers can benefit from, making our writing more polished and professional.

Learning and Adaptation

One of the most significant ways Grammarly is turning us into cyborg writers is through its learning capabilities. Grammarly adapts to our writing style over time, offering personalized suggestions that align with our unique voice. This continuous learning process means that the more we use Grammarly, the better it becomes at understanding and enhancing our writing. It's like having a writing coach that evolves with us, making us better writers with each interaction.

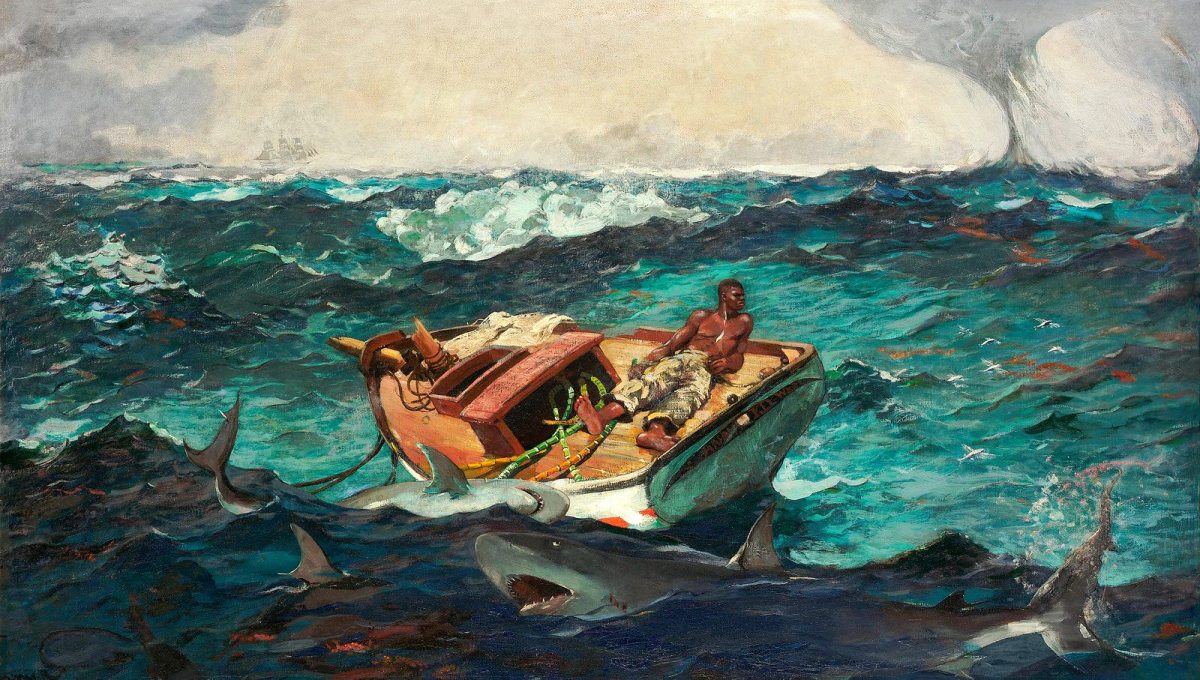

The Cyborg Writer

The term "cyborg" often conjures images of humans with robotic enhancements. In the context of writing, Grammarly serves as that enhancement, augmenting our natural abilities with the power of AI. While we remain the creative force behind our words, Grammarly provides the technical support that ensures our writing is clear, precise, and impactful. This symbiotic relationship between human creativity and artificial intelligence is what makes us cyborg writers.

In conclusion, Grammarly is more than just a writing tool; it's a transformative technology that enhances our writing efficiency, precision, and learning. By integrating AI into our writing process, Grammarly is making us more like cyborgs, blending human creativity with digital precision to create the best possible written communication.

Not bad, not bad at all. Formal and somewhat academic. It’s funny how another AI is helping to sell the product a competing AI is producing. I guess AIs like to stick together.

I asked Claude AI to also write me a short essay on the same subject. Here’s what it produced:

In the digital age, I've discovered an unexpected transformation: Grammarly has turned me into a cyborg writer, a hybrid creature where human creativity merges with algorithmic precision. Each green correction and blue suggestion is a technological implant, rewiring my linguistic neural pathways.

My sentences now emerge pre-optimized, grammatical mutations engineered by an AI writing companion. Passive voice? Eliminated. Awkward phrasings? Surgically removed. Spelling errors? Instantly neutralized. Where once I battled with semicolons and dangling modifiers, now my digital co-pilot seamlessly navigates linguistic terrain.

This symbiosis feels both liberating and unsettling. My writing flows with unprecedented smoothness, yet I wonder: am I composing, or am I being composed? The line between my human intuition and Grammarly's algorithmic suggestions blurs like a soft-focus lens.

I am no longer just a writer. I am a writer-machine hybrid, my prose enhanced by real-time computational linguistics. Grammarly doesn't just correct; it augments, transforming each document into a finely calibrated communication device.

Welcome to the future of writing—where human creativity and artificial intelligence dance in perfect, grammatically correct synchronization.

Oh, wow! Claude AI is much more creative than CoPilot, even using the first person to make it sound like I wrote it. I could have posted that today. Would y’all have guessed it wasn’t me?

How much should we let AI help us?

What if I wrote a nonfiction book and it was good, but with help from an AI, the book was turned into something more readable. Which would you prefer to read? What if it turned my decently insightful tome into something brilliant?

Since Editor is back to working, I have it enabled in Edge, and I have Grammarly enabled in Chrome. What’s funny is they each have different writing suggestions. Either I’m a terrible writer, or neither AI likes my style. I can clear all the edits from Editor, so it looks like my essay is in professionally written, and then switch to Chrome, and Grammarly will claim I’m a horrible writer and make all kinds of suggestions. Should I take them? Or should I just let Claude AI compose my posts?

JWH