by James Wallace Harris, 2/12/24

This essay is for anyone who wants to understand themselves and how creativity works. What I’m about to say will make more sense if you’ve played with ChatGPT or have some understanding of recent AI programs in the news. Those programs appear to be amazingly creative by answering ordinary questions, passing tests that lawyers, mathematicians, and doctors take, generating poems and pictures, and even creating music and videos. They often appear to have human intelligence even though they are criticized for making stupid mistakes — but then so do humans.

We generally think of our unconscious minds as mental processes occurring automatically below the surface of our conscious minds, out of our control. We believe our unconscious minds are neural functions that influence thought, feelings, desires, skills, perceptions, and reactions. Personally, I assume feelings, emotions, and desires come from an even deeper place and are based on hormones and are unrelated to unconscious intelligence.

It occurred to me that ChatGPT and other large language models are analogs for the unconscious mind, and this made me observe my own thoughts more closely. I don’t believe in free will. I don’t even believe I’m writing this essay. The keyword here is “I” and how we use it. If we use “I” to refer to our whole mind and body, then I’m writing the essay. But if we think of the “I” as the observer of reality that comes into being when I’m awake, then probably not. You might object to this strongly because our sense of I-ness feels obviously in full control of the whole shebang.

But what if our unconscious minds are like AI programs, what would that mean? Those AI programs train on billions of pieces of data, taking a long time to learn. But then, don’t children do something similar? The AI programs work by prompting it with a question. If you play a game of Wordle, aren’t you prompting your unconscious mind? Could you write a step-by-step flow chart of how you solve a Wordle game consciously? Don’t your hunches just pop into your mind?

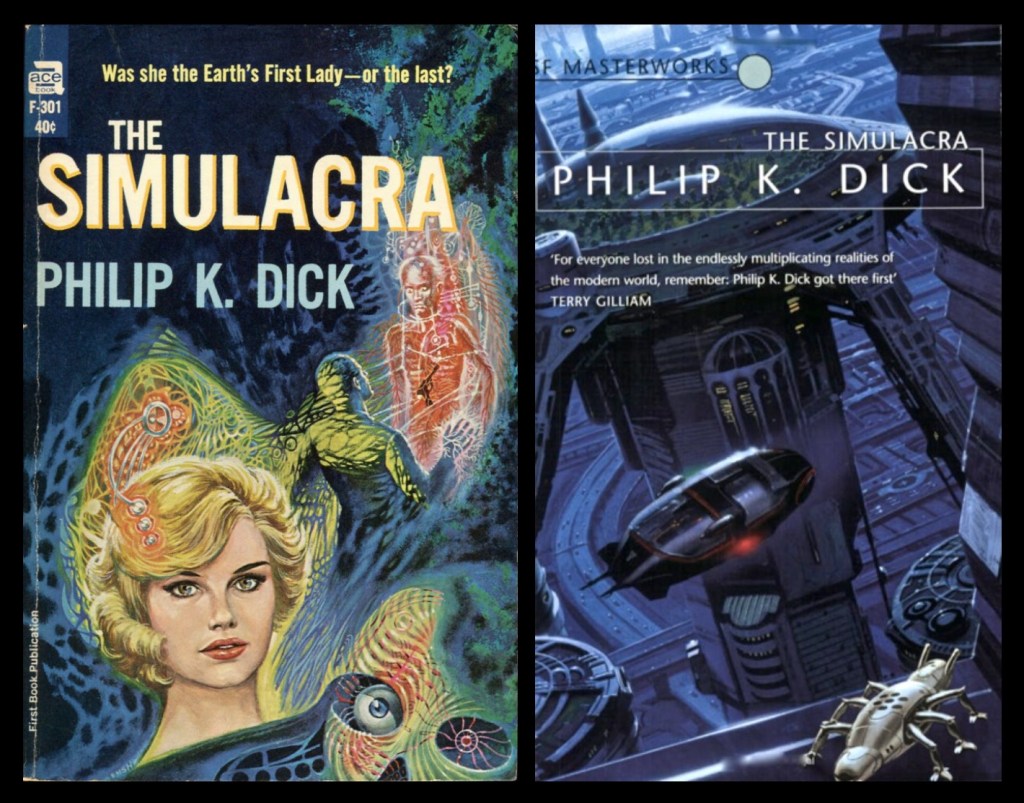

If our unconscious minds are like ChatGPT, then we can improve them by feeding in more data and giving it better prompts. Isn’t that what we do when studying and taking tests? Computer scientists are working hard to improve their AI models. They give their models more data and refine their prompts. If they want their model to write computer programs, they train their models in more computer languages and programs. If we want to become an architect, we train our minds with data related to architecture. (I must wonder about my unconscious mind; it’s been trained on decades of reading science fiction.)

This will also explain why you can’t easily change another person’s mind. Training takes a long time. The unconscious mind doesn’t respond to immediate logic. If you’ve trained your mental model all your life on The Bible or investing money, it won’t be influenced immediately by new facts regarding science or economics.

We live by the illusion that we’re teaching the “I” function of our mind, the observer, the watcher, but what we’re really doing is training our unconscious mind like computer scientists train their AI models. We might even fool ourselves that free will exists because we believe the “I” is choosing the data and prompts. But is that true? What if the unconscious mind tells the “I” what to study? What to create? If the observer exists separate from intelligence, then we don’t have free will. But how could ChatGPT have free will? Humans created it, deciding on the training data, and the prompts. Are our unconscious minds creating artificial unconscious minds? Maybe nothing has free will, and everything is interrelated.

If you’ve ever practiced meditation, you’ll know that you can watch your thoughts. Proof that the observer is separate from thinking. Twice in my life I’ve lost the ability to use words and language, once in 1970 because of a large dose of LSD, and about a decade ago with a TIA. In both events I observed the world around me without words coming to mind. I just looked at things and acted on conditioned reflexes. That let me experience a state of consciousness with low intelligence, one like animals know. I now wonder if I was cut off from my unconscious mind. And if that’s true, it implies language and thoughts come from the unconscious minds, and not from what we call conscious awareness. That the observer and intelligence are separate functions of the mind.

We can get ChatGPT to write an essay for us, and it has no awareness of its actions. We use our senses to create a virtual reality in our head, an umwelt, which gives us a sensation that we’re observing reality and interacting with it, but we’re really interacting with a model of reality. I call this function that observes our model of reality the watcher. But what if our thoughts are separate from this viewer, this watcher?

If we think of large language models as analogs for the unconscious mind, then everything we do in daily life is training for our mental model. Then does the conscious mind stand in for the prompt creator? I’m on the fence about this. Sometimes the unconscious mind generates its own prompts, sometimes prompts are pushed onto us from everyday life, but maybe, just maybe, we occasionally prompt our unconscious mind consciously. Would that be free will?

When I write an essay, I have a brain function that works like ChatGPT. It generates text but as it comes into my conscious mind it feels like I, the viewer, created it. That’s an illusion. The watcher takes credit.

Over the past year or two I’ve noticed that my dreams are acquiring the elements of fiction writing. I think that’s because I’ve been working harder at understanding fiction. Like ChatGPT, we’re always training our mental model.

Last night I dreamed a murder mystery involving killing someone with nitrogen. For years I’ve heard about people committing suicide with nitrogen, and then a few weeks ago Alabama executed a man using nitrogen. My wife and I have been watching two episodes of Perry Mason each evening before bed. I think the ChatGPT feature in my brain took all that in and generated that dream.

I have a condition called aphantasia, that means I don’t consciously create mental pictures. However, I do create imagery in dreams, and sometimes when I’m drowsy, imagery, and even dream fragments float into my conscious mind. It’s like my unconscious mind is leaking into the conscious mind. I know these images and thoughts aren’t part of conscious thinking. But the watcher can observe them.

If you’ve ever played with the AI program Midjourney that creates artistic images, you know that it often creates weirdness, like three-armed people, or hands with seven fingers. Dreams often have such mistakes.

When AIs produce fictional results, the computer scientists say the AI is hallucinating. If you pay close attention to people, you’ll know we all live by many delusions. I believe programs like ChatGPT mimic humans in more ways than we expected.

I don’t think science is anywhere close to explaining how the brain produces the observer, that sense of I-ness, but science is getting much closer to understanding how intelligence works. Computer scientists say they aren’t there yet, and plan for AGI, or artificial general intelligence. They keep moving the goal. What they really want are computers much smarter than humans that don’t make mistakes, which don’t hallucinate. I don’t know if computer scientists care if computers have awareness like our internal watchers, that sense of I-ness. Sentient computers are something different.

I think what they’ve discovered is intelligence isn’t conscious. If you talk to famous artists, writers, and musicians, they will often talk about their muses. They’ve known for centuries their creativity isn’t conscious.

All this makes me think about changing how I train my model. What if I stopped reading science fiction and only read nonfiction? What if I cut out all forms of fiction including television and movies? Would it change my personality? Would I choose different prompts seeking different forms of output? If I do, wouldn’t that be my unconscious mind prompting me to do so?

This makes me ask: If I watched only Fox News would I become a Trump supporter? How long would it take? Back in the Sixties there was a catch phrase, “You are what you eat.” Then I learned a computer acronym, GIGO — “Garbage In, Garbage Out.” Could we say free will exists if we control the data, we use train our unconscious minds?

JWH