by James Wallace Harris, 1/3/24

At 72, I’m still learning how to read.

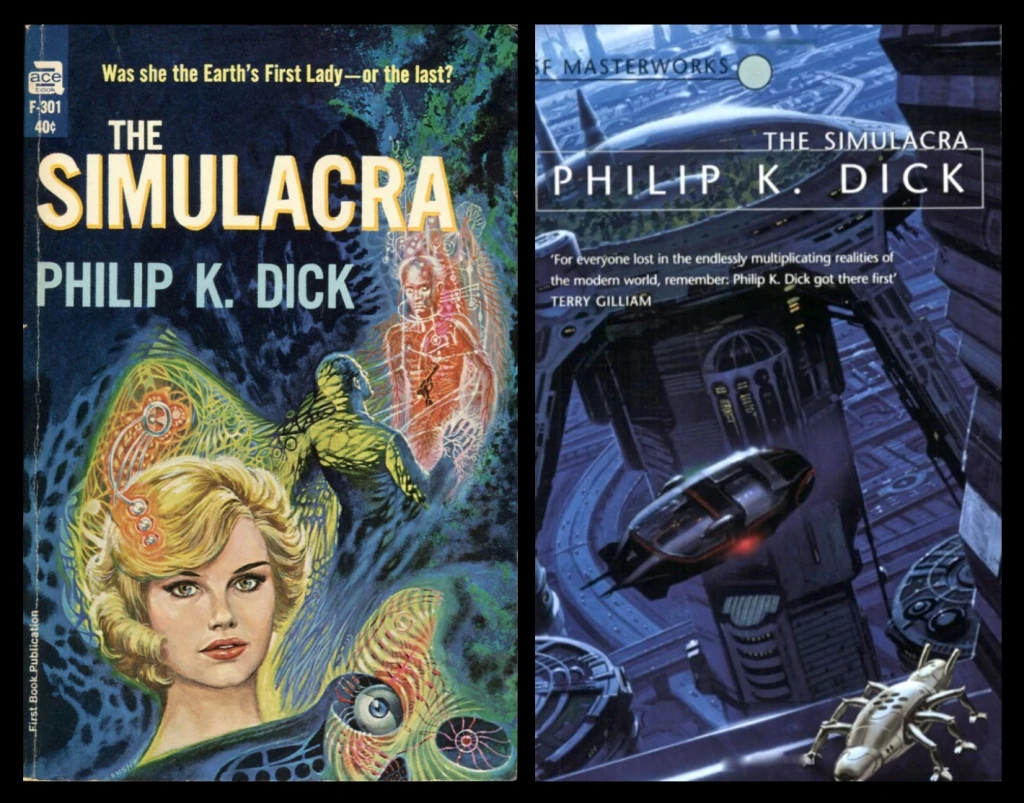

I recently finished the audiobook of The Simulacra by Philip K. Dick and started to write a review for my science fiction blog. That’s when I realized I needed to read the book with my eyes before I could write a proper review. The Simulacra was a complex novel involving several plot threads and dozens of named characters. (Read the plot summary at Wikipedia. Get the book at Amazon.)

From my audiobook experience I found the book compelling, fun, and I was always anxious to get back to listening to the story. I was never confused by what was going on, but when I tried to summarize the novel for my review, I discovered I couldn’t recall all the details I needed to make a coherent description of the story. There were just too many science-fictional concepts. Nor could I describe all the plot threads without researching them.

I won’t describe the book in detail, I’ll do that in my review, but for now, The Simulacra is about a post-apocalyptic world where China attacked America with atomic missiles in 1980, and the U.S. government and Germany combined to form a totalitarian regime called The United States of Europe and America (USEA). It appears to be run by a captivating 23-year-old first lady named Nicole Thibodeaux. However, she has been married to five presidents and always remains young. Since this book was written in the summer of 1963, I assume Dick was inspired by Jackie Kennedy because Nicole spends most of her time charming people, decorating the White House and gardens, and putting on nightly cultural events. But Nicole is also ruthless enough to have people summarily executed, evidently wielding unlimited power. She has access to time travel no less, and one subplot involves her negotiating with Nazis to change the course of WWII. Other subplots involve an insane psychic pianist Nicole wants to play at the White House, the outlawing of psychiatry pushed by the pharmaceutical industry, what happens to the last legal psychiatrist, a pair of ordinary guys who have a jug band that plays classical music who want to perform at the White House, a trio of sound engineers who are trying to chase down the psychic pianist to record, and a small company that hopes to get the contract to construct the next president. This long paragraph barely scratches the surface of the whole novel.

My failure of completely understanding the novel from listening to the audiobook was partly due to aging memory and partly due to the complexity of Dick’s prose. I could have hashed out several thousand words describing what I remembered, although it would have been a bundle of vague impressions. Summarizing what PKD was trying to do was evasive from just listening to the audiobook.

Audiobooks are bad for remembering exact details, which I knew, but was painfully revealed when I tried to read the novel and take notes. I called up The Simulacra on my PC in the Kindle app on the left side of the screen, and launched Obsidian, a note taking program on the left side of the screen. I started reading The Simulacra again, but with my eyes. After two days, getting to the 29% read position on the Kindle edition, I had twenty-eight names, twenty-six plot points, several lists of other details, and several quotes in my notes. I figure there are three to five main plot threads, each involving three or more characters.

More than that, I realized Philip K. Dick had riffed on hundreds of ideas. As I read them, I remembered them, but I realized that while listening, I had not put most of them within the context of the story. It wasn’t until my second reading that I saw all these hundreds of creative speculations as being part of one jigsaw puzzle picture. And I’m not talking about the characters and plots. I’m talking about worldbuilding.

Rereading with my eyes allowed me to stop and ponder. Rereading allowed me to remember the bigger picture. However, listening to the audiobook let me enjoy the story more. The narrator, Peter Berkrot, did voices for each of the characters, and acted out their personalities. Listening to the novel, it felt like I was listening to an old-time radio drama where many actors performed a story.

At one point I got too tired to read and went to bed. But before I fell asleep, I listened to the part I had just read. Berkrot expressed emotions I had not picked up while reading with my eyes, but recalling the scenes made me realize that Dick had put them there. In other words, Berkrot had found aspects of the text I missed and was pointing them out with sound.

Over the ten years since I’ve retired, I’ve been learning the value of rereading books. In fact, I now feel reading a story just once is unfair to the author. It takes two or more readings to see the author’s vision. Reading a work of fiction just once provides one layer of understanding. It’s when we see multiple layers within a work that we start to truly understand it.

Switching back and forth between reading with my eyes and reading with my ears reveals both methods have their advantages. If I read once with one sense organ and reread with another, the two combine to create reading synergy.

For most of my life, I’ve always been concerned with reading more books, but the wisdom I’m gaining from getting old is showing me that both speed reading and reading lots of books is a distraction from deep reading.

Right now, I’d recommend:

- Listen to an audiobook for the first reading to get the big picture.

- Reread with a physical book or ebook to get the details. Read slowly and stop often to ponder.

- Write a review to make deeper sense of a book. Putting things into words pushes us to make sense of things.

- Read reviews and scholarly articles to get other perspectives.

- Reread the book again to bring it all together.

This is what I’m working on with The Simulacra by Philip K. Dick. It’s not considered one of Dick’s better works, but I’m trying to discover if there is more to the novel than its current reputation.

JWH