by James Wallace Harris, 3/3/25

It annoys me more and more that I can’t recall names and nouns. I don’t worry yet that it’s dementia because most of my friends have the same problem. But I’ve been thinking about my ability to remember and realized that I’ve never been good at remembering things.

I know I have aphantasia, which means I can’t visualize mental images in my head. I wonder if there’s a connection between not visualizing images and poor memory? People with astounding memory often use mental images as mnemonics.

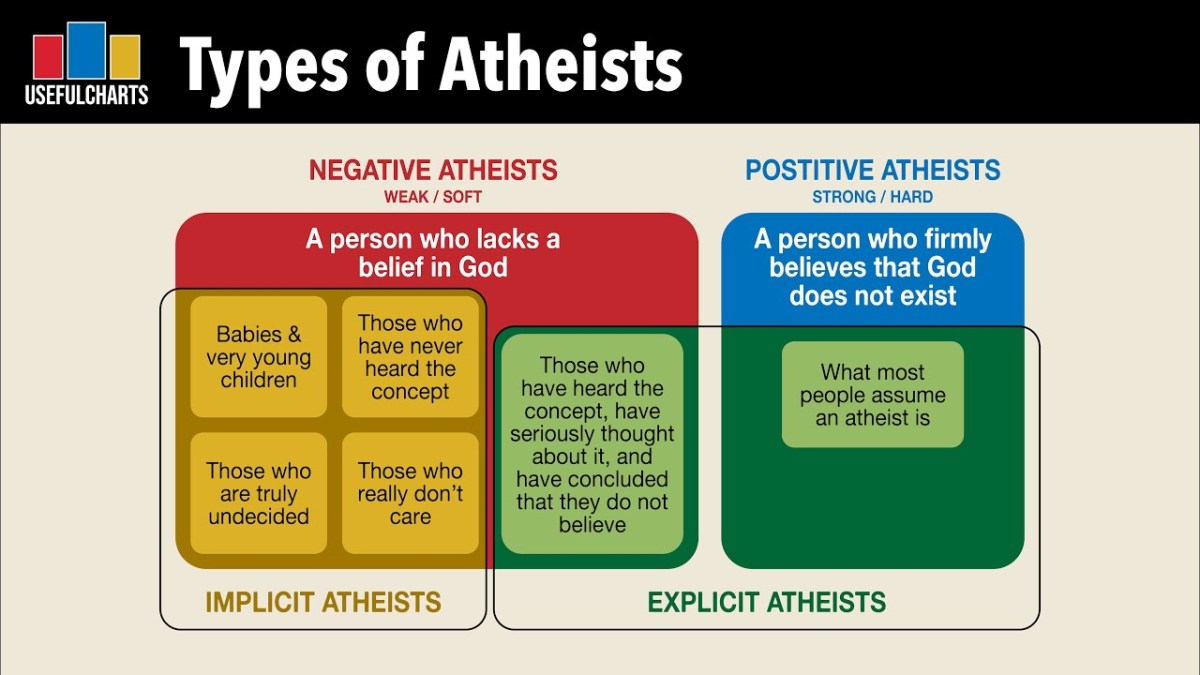

The ability to remember is on a spectrum. On one end of this range, are rare individuals with photographic memories, while at the other end, are a tiny group with no short-term memories.

My new theory. One possible reason I have poor memory is my education. More precisely, how my personality approached learning as a kid. I considered K-12 a thirteen-year prison sentence. I paid just enough attention to pass tests. I mostly got Cs and Bs, with a rare A and D. I remembered things just long enough to pass a test.

I was never motivated to remember for the long haul.

I do like to learn. I’ve read thousands of books. Of course, most of them have been science fiction, but I also love nonfiction. However, information leaves me as fast as I consume it.

I’m starting to wonder if I would have a better memory if I had developed a different approach to school and learning. Primary and secondary education aim to give kids a well-rounded education. And in college, over half the courses are required.

The idea is we should learn as much as possible about the world. Is that a valid approach? After school and college, we specialize in whatever our work requires, and become selective about what we study for fun. Those subjects are what we remember best.

Reality is too big to know everything. What we need to learn is how to coexist with reality. We need the knowledge to fit in and survive. Would knowing more about fewer subjects help? Or would memorizing the deep dynamics of how things work better yet?

I do believe the more we know, the wiser we are. But there are limits to what we can understand and memorize.

I’m currently reading Nexus by Yuval Noah Harari. In chapter 2, Harari shows how fiction drives our societies, not truth. We live by stories we want to believe. It’s much easier to vaguely understand fiction than to learn the details of reality. For example, more people accept The Bible than biology. That suggests a natural tendency to minimize how much we know.

That would be okay if the Earth were sparsely populated. But we live in dense, complex societies racing at the speed of computer networks and artificial intelligence. Living by fiction is fine if the year is 500 BCE, but we live in 2025. CE.

Let me give one example of what I mean by learning less to know more. I’ve been reading American history books to understand how our society got to now. That gives me a certain level of wisdom about our problems. However, I’m also reading about French history, especially the French Revolution and 19th century history. Seeing the parallels ups my level of understanding. But do I need to read the history of every country now and then? What I see is common dynamics. Reading more histories will give me more examples of the same dynamics.

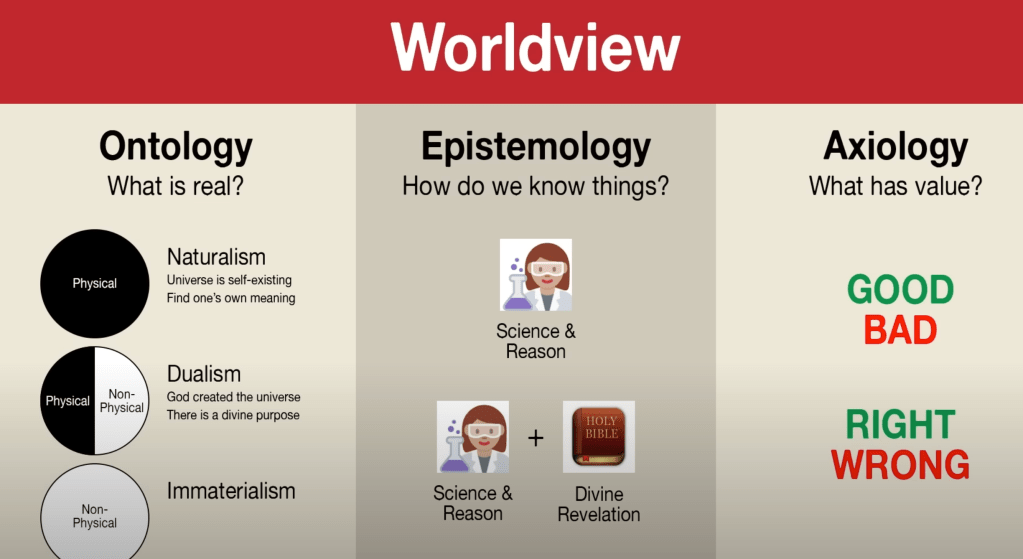

The same is true of religion. I like studying the history of the Bible. I’ve also studied Buddhism and Hinduism. As I do, I see common dynamics at work. Harari’s new book Nexus points out the common dynamics of society and history.

The educational philosophy I experienced growing up pushed me to memorize a million details. What I needed to understand and remember is the fewer dynamics of reality.

People like to live by fiction because it’s easier. Politics is currently overwhelmed by fiction. Read Nexus to understand why I say that. The question we have to answer is if we can reject fiction.

Real information is seeing patterns in reality. Wisdom is seeing patterns in the patterns. The only real cognitive tool we’ve ever developed to understand reality is science. However, it’s statistical, and hard to learn and understand. We live in a time of simplex thinking. People see or are told about one pattern and they accept that as a complete explanation of reality. All too often, that pattern is based on a cherished story.

We can’t live by memes alone. Nor can we live by infinite piles of memorized details. The only way to understand is to observe consistent patterns. But it has to be more than two or three. That can lead to delusions. Even anecdotal evidence of ten occurrences could still deceive. How can this lead to learning more from less? It’s a paradox.

Last year, I read a three-volume world history. It provided hundreds of examples of strong man rule over thousands. of years. But how many kids, or citizens can we get to read a three-volume world history? Would a listing of these leaders, including the wars they started, and the numbers of people who died because of their leadership be just as effective? Would all the common traits they shared help too? Such as wanting to acquire more territory, or appeals to nationalism?

Could we create a better educational system with infographics and statistics? I don’t know. I do know I tried to process too much information. I also know that I only vaguely remember things. Memory has limits. As does wisdom.

JWH