When we were young we’d all dream of growing up to be in the movies, or rocking out on stage, or flying F-16s, or writing great novels, or rocketing to Mars – the kind of careers that look exciting when we don’t know much about how the world works. Few kids achieve their childhood ambitions. Most of us get regular nine-to-five jobs, and just daydream about the ways we’d really like to be spending our hours.

I always wanted to be a science fiction novelist. Because I loved reading science fiction books I assumed I’d love writing them. As a teen I didn’t know just how wrong that logic was. I should have wished to grow up and become a professional reader. Even as a teen I knew kids who compulsively wrote stories. I didn’t, but I assumed one day I’d get an urge and start. I should have known better – the only time I wrote was when I took a creative writing class in high school or college and deadlines forced me to write.

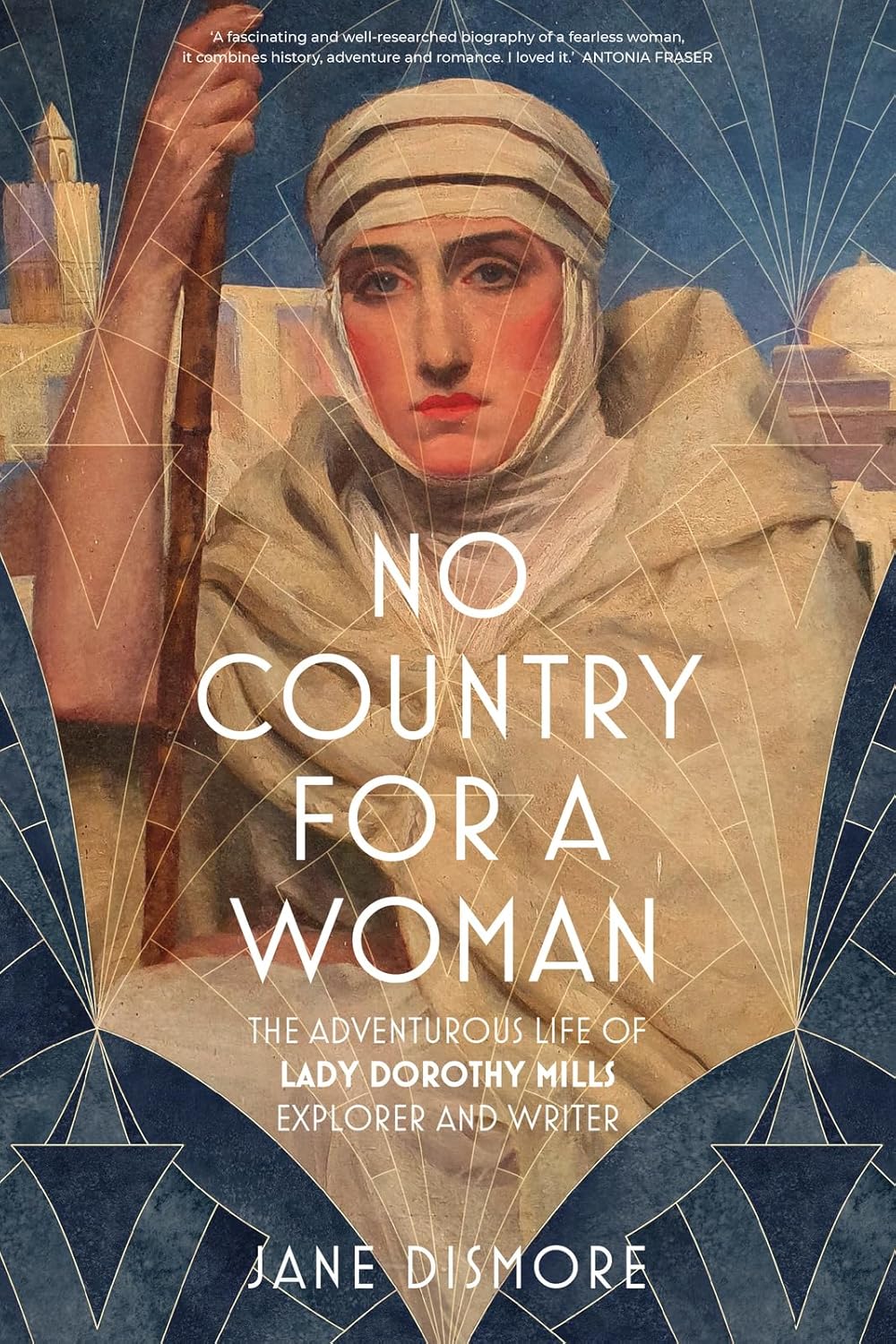

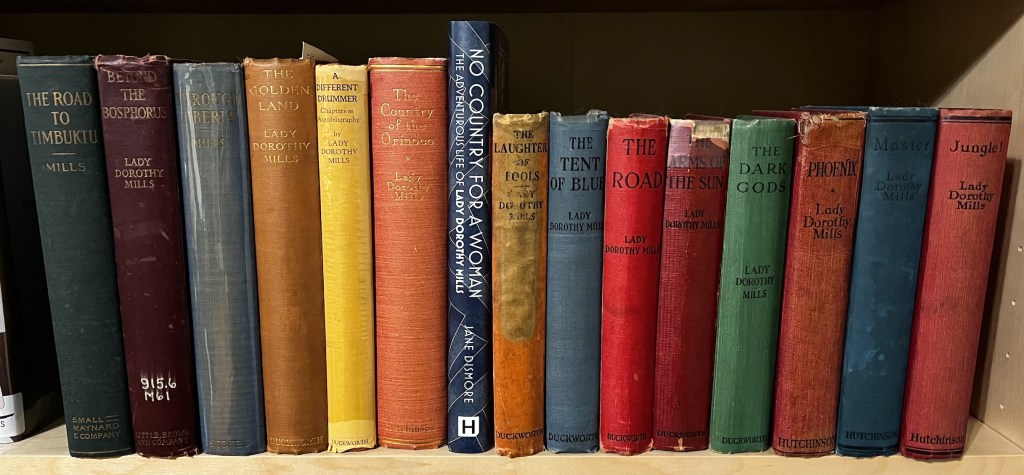

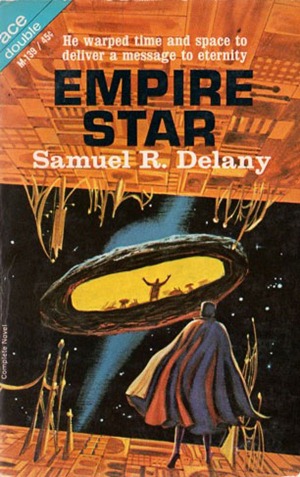

Around 1971 or 72 I went to my first science fiction convention in Kansas City, The Mid-America Con. I was about 20 at the time and I met a lot of writers there. But the one that impressed me the most was this kid who looked about my age who told me he had just sold his second story. He was George R. R. Martin. I was so impressed and jealous at this very young writer. I felt like Comet Jo from Empire Star by Samuel R. Delaney, when he first met Ni Ti. Comet Jo was a naïve rube with dreams that met a guy that had already done everything Comet Jo’s dreamed of doing.

That was a revelation at that convention – writers write. And if you want to grow up to write giant bestsellers you’ve got to start young and practice. Delany was also a writing prodigy, and he dealt with the subject somewhat in Empire Star.

Those early experiences meeting writers should have convinced me to stop daydreaming about writing, but fantasy ambitions aren’t that easily destroyed. And wanting to be a novelist is different. Some people don’t start writing until late in life, so I figured I had plenty of time. If I had wanted to be a football player, fire fighter or astronaut, I’d have known I was over the hill when I turned thirty. Now that I hope to retire next year, my old fantasy ambition is returning. I’ll finally have the time. Probably lack of time wasn’t the real reason I never wrote, and it will be brutally revealed to me soon. I have to be self-aware enough to recognize that wanting to write and not might be my natural state for my whole life. But not giving up also seems to be a trait that never goes away either.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about what it means to be a novelist, the grittily specific job details. I came across “Good Writing vs. Talented Writing” by Maria Popova over at Brain Pickings. She quotes About Writing by Samuel R. Delany,

Either in content or in style, in subject matter or in rhetorical approach, fiction that is too much like other fiction is bad by definition. However paradoxical it sounds, good writing as a set of strictures (that is, when the writing is good and nothing more) produces most bad fiction. On one level or another, the realization of this is finally what turns most writers away from writing.

Talented writing is, however, something else. You need talent to write fiction.

Good writing is clear. Talented writing is energetic. Good writing avoids errors. Talented writing makes things happen in the reader’s mind — vividly, forcefully — that good writing, which stops with clarity and logic, doesn’t.

This is very telling. The obvious reason why I’m not a writer is the lack the talent. But what is talent? Is it a gene? Is it being born with a muse? I am reminded of a book, Talent Is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else by Geoff Colvin. Talent is mostly hard work. If I lack talent its because I’m lazy. But we also know that some people work very hard and never succeed, even if they put in their 10,000 hours of practice.

But even this isn’t the issue I want to explore. What skills are really required to write a novel? Every time I try to write fiction I hit a brick wall. Writing fiction requires having imagination the size of Jupiter. I don’t know if you have ever wanted to write novels, plays or movies, but have you ever thought about what goes into creating a great story? I’ll use movies and television shows for example over books because they are more familiar to people.

Let’s think about of some of the poplar shows on TV like Breaking Bad or The Game of Thrones and dissect how they are put together, and what makes them successful. Both stories are incredibly addictive. I believe each has all the elements that make for great fiction. Maybe not Shakespeare great, but great for seducing people into their story worlds.

Story World

The first aspect of great fiction is creating the story world. This goes way beyond setting. And I’m not talking about the world building of fantasy and science fiction, but the creating of a whole fictional reality. Even when a story is realistic like Breaking Bad, or To Kill a Mockingbird, its creating a whole story world, time and place, with endless defining details. As much as we’d like to believe that To Kill a Mockingbird is an accurate portrayal of the past, it isn’t. Every written story involves two imaginations, the writer and the reader. With movies and television shows, the director, the actors, set designers, cinematographers, costume makers, special effects wizards, also add their imaginations to creating the story world. But with novels and short stories, the author suggests everything in words, and the readers bring their own imaginations to decode their version of the story world. Watching The Game of Thrones, meanings most everything has been envisioned for the audience, but readers of the book all imagine something different.

The reason why the Harry Potter books are so great is because of the complete story world that J. K. Rowling created.

If you ever think about becoming a writer, do this experiment. Each time you read a book or watch a movie, try and list everything that had to be invented by the imagination of the writer. Most stories involves thousands of imaginative decisions, and stories like The Game of Thrones or the Harry Potter books, involve tens of thousands of mental creations, maybe even hundreds of thousands. These novels run 100,000-200,000 words, or more. Thinking tunic or sword are small decisions, but thinking up the details of Quidditch takes some real work.

Characters

It’s hard to say which comes first, characters or story world. Often writers create characters that generate their story worlds. Other writers start with the story world first and then create the characters that belong in that story world. Either way, creating characters is very hard work. And the best stories seem to have lots of characters. Would The Game of Thrones or Breaking Bad stories be so compelling if they only followed a handful of main characters? Walter White is a tremendous creation, but the depth of his character works because of his relationship with Skyler, Jesse, Hank, Walter Jr., Saul, Gus, and so on. Think about every detail that went into creating Gustavo Fring? Does thinking up those kinds of character details come from genes, muses or what? Most great writers are great observers of people.

One of the hardest things to create for your characters is their dialog. Bad writers make all their characters talk like themselves. Great writers make all their characters sound like diverse people from all over the world. Listen to audio books, especially the ones that have narrators who do voices for each character. It’s not just the sound of the voice, or the accent, but how each character phrases their words.

Each character has to have their own background and history, but more important than that, each character has to have their own motivations and desires. When we read novels generally they are driven by one or two people’s stories. But every character that walks into a scene has their own agenda. Bad writers create minor characters to show off the main characters, but great writers create minor characters that want to make the story their own. Every character should be trying to steal the scene for themselves, because in reality, every person thinks they are the center of the universe. Nobody wants to be a red shirt.

Plot

Plot is what drives the story forward. Will Walter make enough money to leave his family secure before he dies of cancer? Who will take the Iron Throne from Joffrey Baratheon?

Writing a plot requires imagining a beginning, middle and end. However, modern binge worthy TV shows have no end, but are sophisticated soap operas. Readers want a satisfying conclusion at the end of the book, even if its part of a series. Readers love feeling the need to keep turning pages hoping to find out what happens next.

Standalone stories, like non-series novels, and movies, have plots that lead to a satisfactory resolution of a problem revealed at the beginning of a story. Soap opera like stories depend on a series of conflicts that get resolved from time to time. Great stories will bring the story to a climax, and present an epiphany.

I saw Star Trek Into Darkness yesterday. It has the same plot every time. Kirk and Spock play out their now famously cliché character traits while battling a almost impossible-to-beat foe, with all the minor characters also getting to reinforce their now standardize character traits. And we love this because it reinforces the familiar and nostalgic essence of what we think of as Star Trek. Sometimes plots involving giving the audience exactly what they want.

On the other hand, new stories must give readers and audiences something they never seen before. Shows like Breaking Bad, Big Love, Deadwood, Shameless, Girls, etc. find ways to present new and very different plots. Let’s face it, some of us are very old and have been consuming fiction for a very long time, and getting jaded to routine plotting is all too easy.

Conflict

Even though I greatly admire The Song of Fire and Ice for its story world, I have to nick it for stretching to the story out too long. It’s one giant potboiler, generating a steady stream of conflicts and cliffhangers. My favorite character is Arya Stark, who gets involved in one misadventure after the next. She never seems to get anywhere, but she always has something life threatening to deal with. But that’s how you keep readers and watches involved. Characters need conflict to drive them forward in the story, and creating imaginative conflicts is another trait of a good writer.

To me, the masters of fictional conflict are the creators and writers of Breaking Bad. Not only do they keep their characters busy, but they create original, unpredictable conflicts that we never see coming. When I think Jesse is going to have a standard shootout with a villain, Walter shows up at the last second and runs the villain over with his car. The cliché feeling is to want Jessie to kill the guy. We the audience are aching for Jessie to kill the guy. And then out of nowhere Walter runs him over. That’s great plotting and creative conflict resolution.

Summing Up

I don’t know if creating imaginative story worlds, great characters, compelling plots and satisfying conflicts requires an innate talent. Is it an ability that can be acquired through long study and practice? Most books are not that creative. Thousands of novels are published every year that don’t sell or find fans. Many of them are competently written. Delany might be right, that good writing is common, but bad, and talented writing is special. Or it could be all those mundane story tellers just didn’t work hard enough to be distinctive. Maybe creativity comes after ten rewrites, or twenty.

I feel all the stories I’ve written so far fail because I didn’t push myself hard to enough to be more creative. I would like to know if I could push myself to work harder would I be more creative? I have a novel I’m working on now and I feel it doesn’t even achieve 1% of what it should do. And I have a sick feeling that even if I worked a hundred times harder it might only succeed at the 10% level. Maybe if I had a natural talent for story telling I could achieve 90% success with far less work. But I tend to think talented people are just people who wrote dozens of practice novels and earned their skills at faster creativity.

I have two challenges to test. First, can I learn to write after I retire, when I have more time to work harder? And second, is it possible for someone in their sixties to become creative late in life? I’m not delusional, I know I’m in physical and mental decline. I’ve already decided that writing a novel is too ambitious for this test, and that I should aim for success with short stories.

Since 2002 I’ve had a renaissance with my love of fiction because of Audible.com and audiobooks. I have discovered that listening is the best way for me to study great writing. Listening is like having a powerful magnifying glass for studying fiction. And in the past year, I’ve gone back to studying fiction with eye ball reading. What I learned from hearing lets me see words in a new way. The more I study, the more I realize how little I knew about how fiction is put together. I might have discovered that in my teens if I had actually tried to write fifty or a hundred stories back then. You can’t understand fiction completely until you write it.

I don’t know if having all my time free is enough to find success at writing fiction. Whether I succeed or not, the attempt will be a great learning experience.

JWH – 5/27/13