by James Wallace Harris, 12/8/24

The 1960 U.S. presidential election is the first one I remember, but just barely. I was eight years old. My father was for Nixon and my mother for Kennedy. I decided I liked Kennedy because he was younger, more dynamic and had a good-looking wife. Even at eight, good looking women were often a deciding factor. I remember getting in a fight in the school playground because I was for Kennedy and the other kid was for Nixon. Neither of us got to decide the issue because a teacher pulled us apart.

During the Kennedy years I didn’t watch TV news. I would sometimes stay home from school to watch the Mercury space launches. Back then the TV news departments of each network would take over all broadcasting. In the first half of the 1960s, the space program was about the only real-world activity I paid any attention to.

I did pay some attention during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, mainly because I lived on Homestead Air Force Base, and everyone talked about it constantly. I remember having duck and cover drills at Homestead Air Force Base Elementary, but I was disappointed when there were no real A-bombs dropped. (I was very immature for my age.)

I didn’t become a news watcher until Kennedy’s death. I remember that weekend, my family watched the news constantly, and the following week too. That’s when I started following Walter Cronkite. I turned twelve three days after Kennedy was shot.

The news also became exciting in February of 1964 when The Beatles came to America. It was during 1965 that older boys I knew began worrying about being drafted, and I started paying attention to news about Vietnam.

The CBS Evening News was my main source of information about life beyond my own little world during the 1960s. I sometimes got to see The Today Show on NBC because my mother watched it while making breakfast. I liked that show because I found Barbara Walters hot. (Okay, I’ve already said I was a weird kid.) Sometimes I would watch news specials or documentaries. While in the ninth grade (1965-66) I had a civics course. But for the most part I just wasn’t that aware of what was going on in the world except for Top 40 AM music.

I don’t remember reading the paper, The Miami Herald, until 1968. I did start to read magazines in 1965, but that was haphazard. People would give my parents copies of Life, Time, Newsweek, Look, Saturday Evening Post, and National Geographic from time to time, and I found them fascinating. On my own, after 1965, I would buy Popular Science, Popular Mechanics, and MAD Magazine. During twelfth grade (1968-69) my English teacher got me interested in literary fiction, and I subscribed to Saturday Review with money I made from working in a grocery store. I really didn’t understand it though. In late 1968 or early 1969, I got hooked on Rolling Stone magazine and sometimes bought Creem when it started publishing.

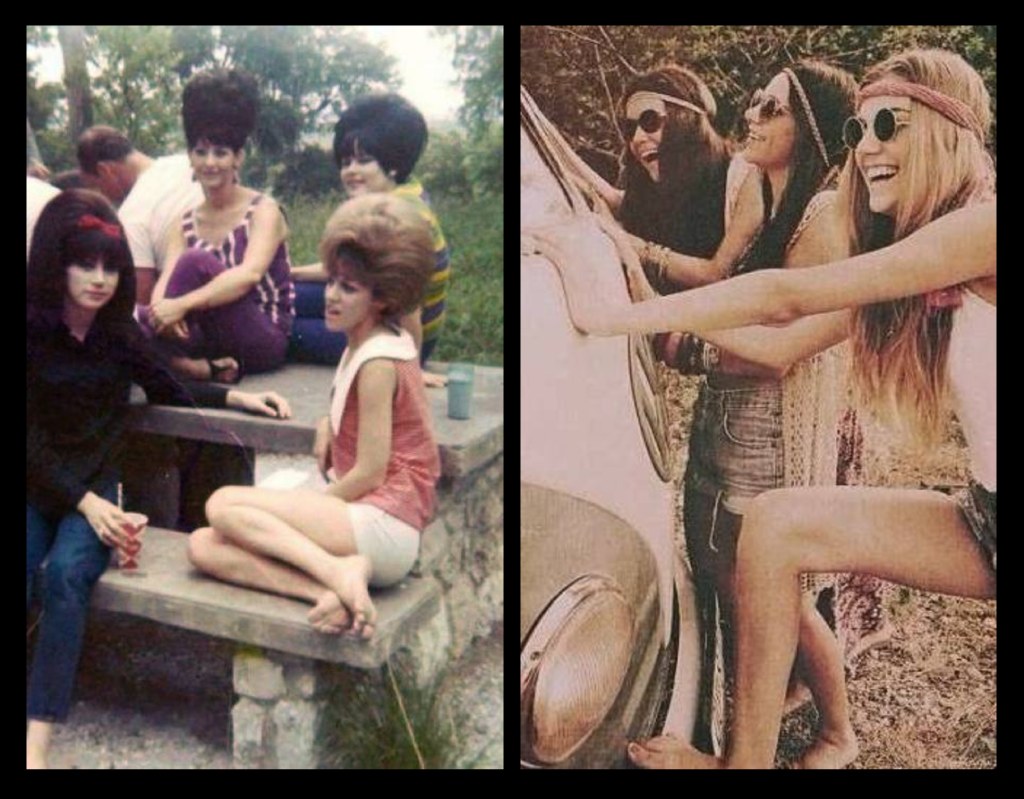

A whole lot of what I knew about the counterculture came from Life Magazine.

If you think about it one way, television and magazines offered a fairly diverse view on what was happening in the world, but squinted at it another way, it was a rather limited view.

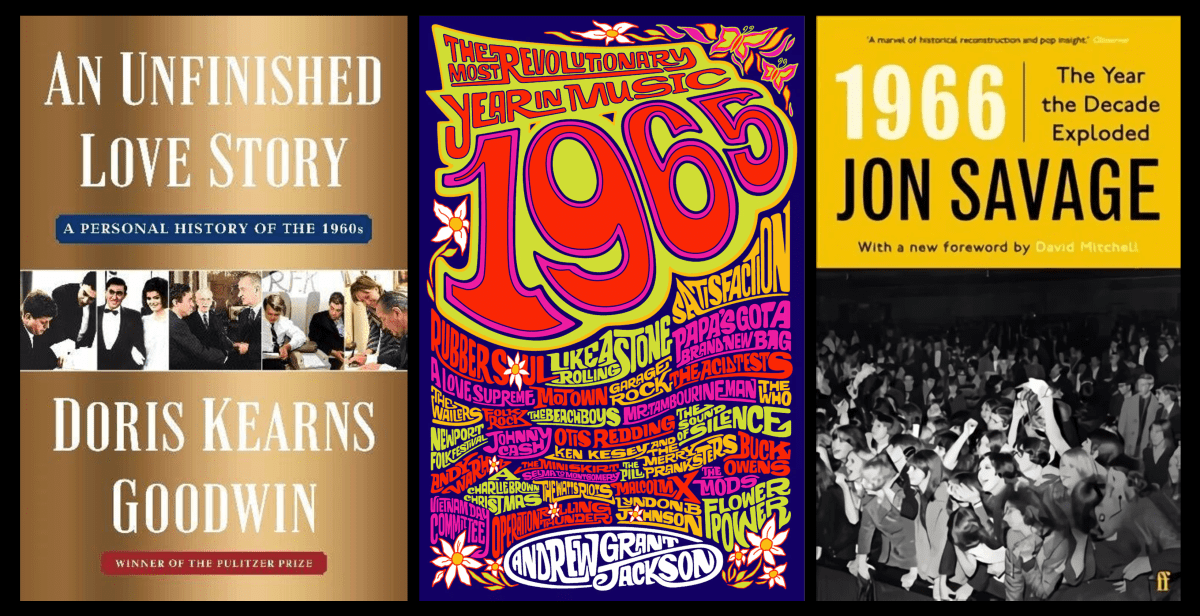

In December 2024, I’ve been reading three books about the 1960s that explore events I encountered in two minute stories on TV, or read about in a few pages in a magazine when they first happened. Some of those short snippets of current events made huge impressions on me as a kid. They shaped who I thought I was. The history books makes me realize I was mostly uninformed.

The reality of the 1960s is I was a kid going to school every day except for long summer vacations. I started 1960 in New Jersey but moved to Mississippi then to Florida then to South Carolina back to Florida, then Mississippi again, and back to Florida. I went to thirteen different schools during the 1960s. The only newsworthy event I saw live was the launch of Apollo 8. I had a chance to see Kennedy in 1962 when he came to Homestead Air Force Base. They let us out of school to see him, but me and my friends went fishing instead. My sister was at Dinner Key Auditorium when Jim Morrison flashed the crowd. I got to meet an astronaut in 1968, but I’ve forgotten which one. And this is hardly newsworthy. I got to see Cream play during their farewell tour in 1968. Oh, and I attended one SDS rally.

In other words, I experienced the legendary Sixties mostly via AM radio, television, and magazines. I did have long hair sometimes, and I sometimes messed around with drugs, but I was hardly a hippie or a radical. I did get into the counterculture more in the 1970s, but that’s another story.

The point of this long-winded essay is I’m now reading history books about years I lived through. I can contrast my memories to behind the scenes accounts of things I got from soundbites. That’s quite enlightening.

We live with the illusion that we think we understand what is real and true. We delude ourselves that we make decisions on relevant information. But we don’t. If I could have read the history books about the sixties I’m reading in old age when I was young, I could have gotten closer to seeing reality.

Timothy Leary and Aldous Huxley, two heroes of my youth, claimed that LSD opened the doors of perception, and that might be true on a nonverbal level, but a deep reading of history books is far greater at revealing reality that we can comprehend on a verbal level.

Lately, I’ve been reading that reading is going out of fashion with young people. That’s a shame. Even back when I was a teen, and only got superficial understandings about the events around me from superficial news sources, it did make me more aware.

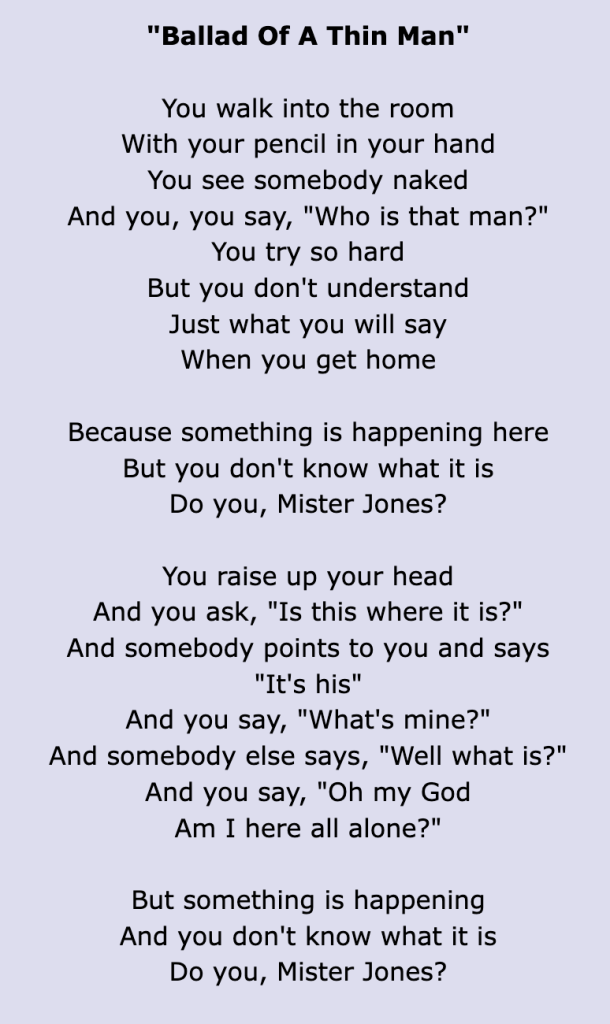

The three books above are filling in details on things happening around me as I was growing up. I’m reminded of Bob Dylan’s “Ballad of the Thin Man.”

I realize I’ve been Mr. Jones my whole life, and I’m still trying to figure out what happened.

JWH