by James Wallace Harris, 12/11/24

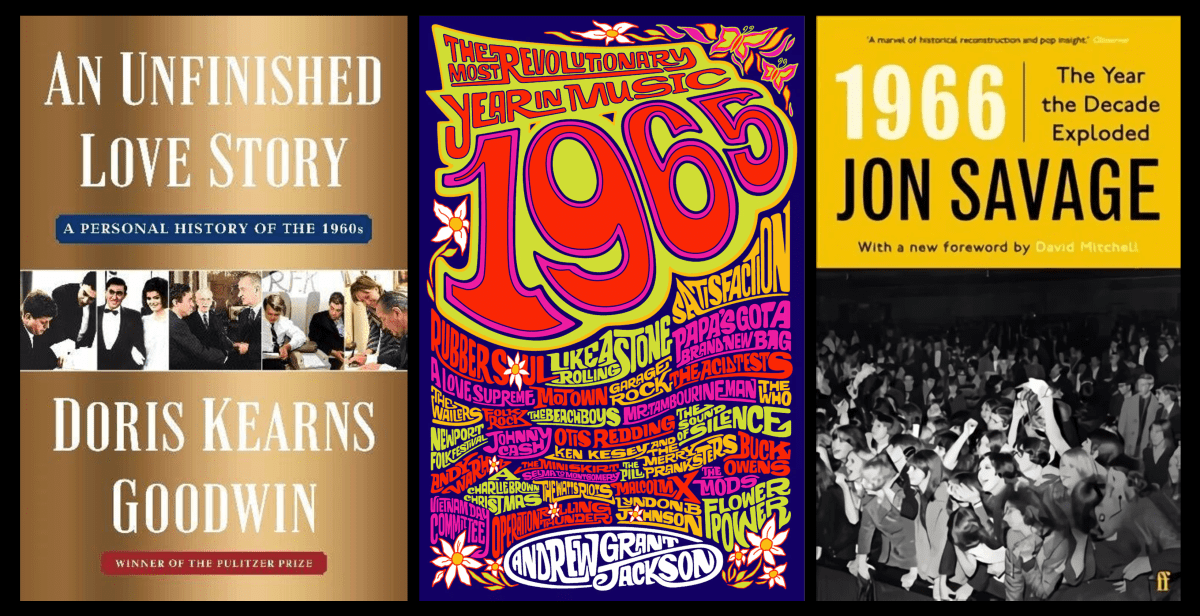

I recently read An Unfinished Love Story by Doris Kearns Goodwin. It’s about how Doris and her husband Richard went through dozens of boxes containing papers that Richard saved from his time as a speechwriter for John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Baines Johnson, Eugene McCarthy, and Robert Kennedy. Richard was in his eighties and wanted to write a memoir about those times. Doris agreed to help him.

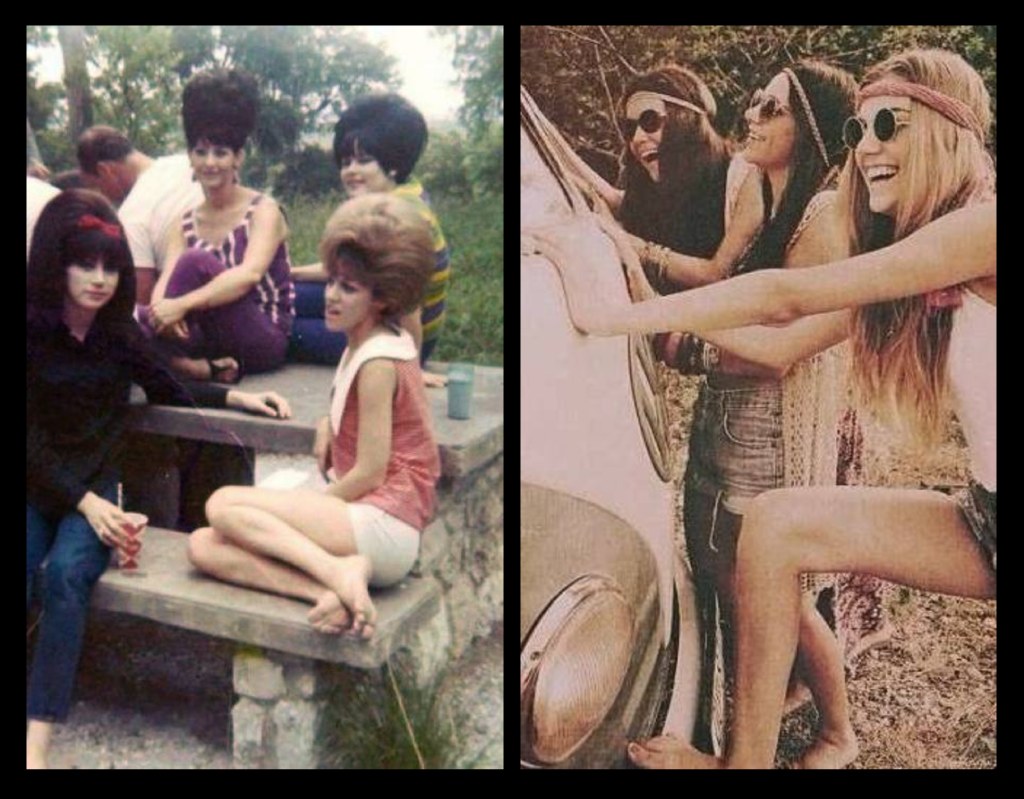

The book is subtitled “A Personal History of the 1960s.” An Unfinished Love Story resonates with me because I lived through that decade too. I’m now rereading their book closely. I want to comprehend what happened in the 1960s and reconcile it with my memories. I do that by looking up original sources mentioned and studying them.

However, I’ve hit a cognitive barrier. I’ve never been a great student, much less a scholar. I have trouble focusing. I can’t stick to any subject long enough to comprehend it. These failings are getting worse as I age.

I’ve discovered a tool that helps me understand my limitations. Maybe it will help me overcome them. That tool is Google NotebookLM. It’s an AI tool that digests information. You link to web pages or upload your documents, and it will analyze that content and then create several kinds of summaries.

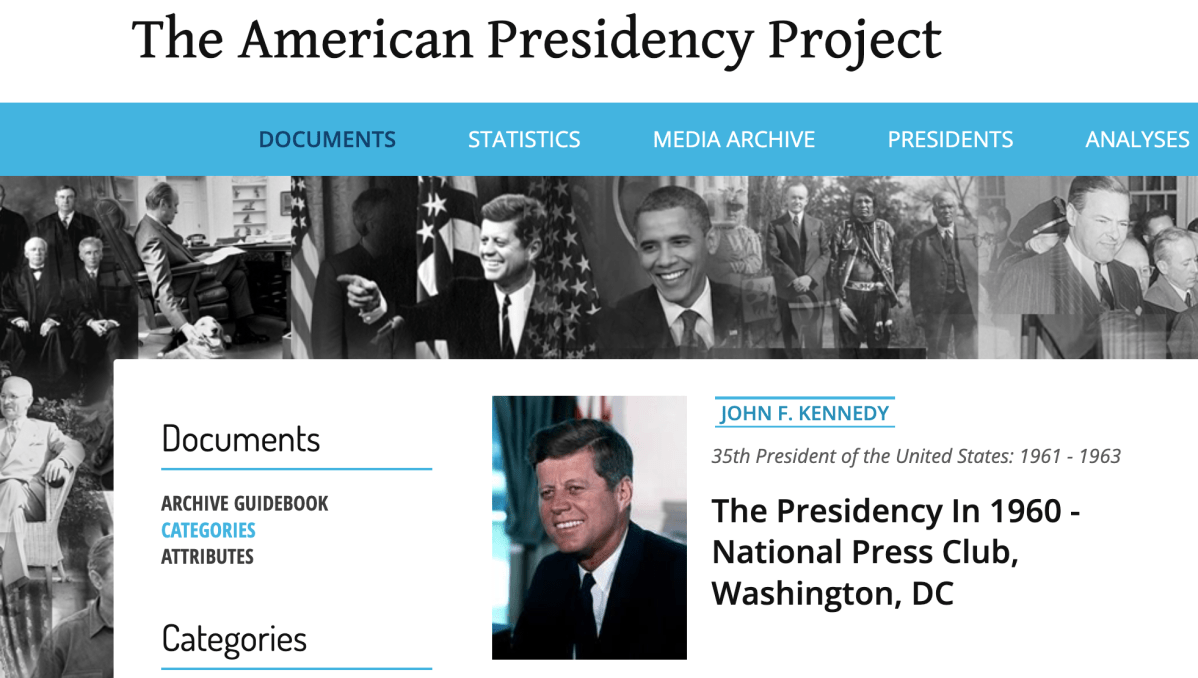

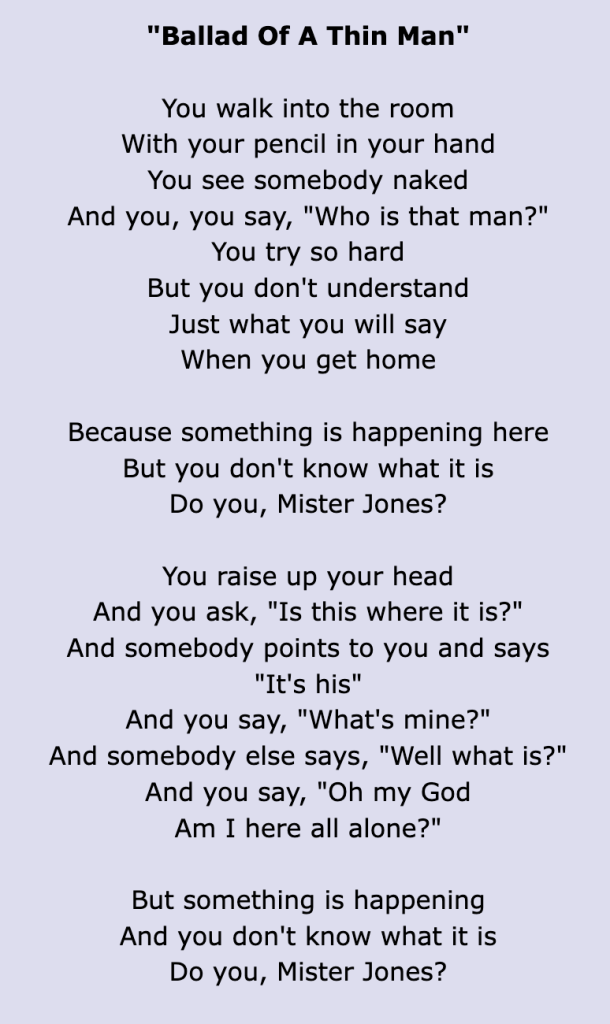

I tested Google NotebookLM with a speech that Richard Goodwin helped write for John F. Kennedy when he was campaigning for president in 1960. It was given at the National Press Club on January 14, 1960. You can read it here. I also gave it this article about that speech. NotebookLM then generated several files that summarized the content of those two documents. The most startling was an AI-generated podcast. You can listen to it here. (You’ll need a free Google account, but anyone using Google email should already be logged in.)

That podcast sounds like an NPR segment. It’s spooky how real the two people sound. But the technology to produce this artificial conversation isn’t what I want to showcase. It’s how NotebookLM understood the speech. It’s a level of reading comprehension that I envy. If I spent a week studying that speech I don’t think I could reach that level of understanding.

Damn, damn, damn!

First of all, Kennedy’s speech was a distillation of extensive knowledge of American political history by Kennedy, Richard Goodwin, and Ted Sorensen. Kennedy expected his audience to decode that knowledge, and to understand his plan for the coming decade. I doubt few did, especially at the level that NotebookLM did.

From reading An Unfinished Love Story, I believe Richard Goodwin could process knowledge like NotebookLM, which is why he was such a brilliant speechwriter. I can’t do anything like that. From this experience, I want to study the results produced by NotebookLM to see if I can learn from it.

Even when I think I understand what I read, I doubt I comprehend even ten percent. I’m quite sure a scholar could write a five-hundred-page book just about that one speech.

NotebookLM created several results. I want to study what it does and see if I can learn to use its techniques.

Here is the summary version.

Briefing Doc: John F. Kennedy's Vision of the Presidency

Sources:

"All notes 12/11/2024" (Study Guide and FAQ on Kennedy's Speech)

"Pasted Text" (Full Text of Kennedy's Speech at the National Press Club, January 14, 1960)

Excerpts from "The Presidency in 1960 (Remarks at the National Press Club) | Teaching American History"

Main Themes:

Active and Engaged Presidency: Kennedy argues for a strong, proactive president who actively shapes policy and drives the national agenda. He rejects a "detached, limited concept of the Presidency" in favor of a leader willing to "place himself in the very thick of the fight."

Legislative Leadership: The president must be an active participant in the legislative process, not simply a "casual bystander." This includes initiating legislation, collaborating with Congress, and using his influence to ensure passage of vital bills.

Party Leadership: Kennedy believes the president must be an active leader of his political party, utilizing its resources and working closely with party leadership to advance his agenda and strengthen the democratic process.

Moral Leadership: The president must not only represent prevailing sentiment but also inspire the nation, set a high ethical standard, and mobilize the public to address challenges and seize opportunities.

Key Ideas and Facts:

Critique of Eisenhower: Kennedy contrasts his vision with Eisenhower's perceived passivity, arguing that the nation needs a more engaged leader for the challenges of the 1960s. He criticizes Eisenhower's preference to remain above politics, stating, "no President, it seems to me, can escape politics."

Historical Examples: Kennedy invokes presidents like Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, and Wilson as exemplars of his ideal. He highlights their willingness to use presidential power, exert legislative leadership, and champion moral causes.

Constitutional Vision: While acknowledging the importance of Congress and cautioning against executive overreach, Kennedy views the presidency as the driving force in the American system. He stresses the president's unique role in foreign policy and domestic policy initiation.

Four Key Roles: Kennedy outlines four essential roles for the modern president: Chief Executive, Legislative Leader, Party Leader, and Moral Leader. Each role requires active engagement and a willingness to utilize the full resources of the office.

The Lincoln Anecdote: Kennedy uses the story of Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation to illustrate the kind of decisive and resolute leadership he believes is essential for the presidency. "Lincoln's hand did not tremble. He did not hesitate. He did not equivocate. For he was the President of the United States."

Important Quotes:

On the need for an active president: "The American Presidency will demand more than ringing manifestoes issued from the rear of the battle. It will demand that the President place himself in the very thick of the fight."

On the president's role as Chief Executive: "He must be prepared to exercise the fullest powers of his office – all that are specified and some that are not."

On the importance of legislative leadership: "The President must initiate policies and devise laws to meet the needs of the nation. And he must be prepared to use all the resources of his office to ensure the enactment of that legislation – even when conflict is the result."

On the president's responsibility as party leader: "If he neglects the party machinery and avoids his party's leadership – then he has not only weakened the political party as an instrument of the democratic process – he has dealt a blow to the democratic process itself."

On the importance of moral leadership: "We will need in the sixties a President who is willing and able to summon his national constituency to its finest hour."

Discussion Points:

To what extent does Kennedy's vision of the presidency align with the principles of a constitutional republic?

Does Kennedy sufficiently address the potential risks of an overly powerful executive branch?

How does Kennedy's vision compare to the presidencies that followed him?

This briefing document summarizes the main themes and key ideas of John F. Kennedy's vision for the presidency. It is important to note that this is just one interpretation of his speech, and further analysis and discussion are encouraged.

Here is a FAQ it generated:

FAQ: John F. Kennedy's Vision of the Presidency

1. What is the central theme of John F. Kennedy's speech at the National Press Club?

This speech, delivered in January 1960 during his presidential campaign, focuses on Kennedy's vision for the modern presidency. He argues that the American people deserve to understand a candidate's philosophy regarding the presidency because it shapes their approach to all other issues.

2. How does Kennedy differentiate his view of the presidency from President Eisenhower's?

Kennedy critiques the "detached, limited concept of the Presidency" he observed during the Eisenhower administration. He advocates for a more active and engaged president who proactively addresses pressing issues and drives the national agenda. He contrasts this with Eisenhower's perceived passivity and delegation of responsibilities.

3. What historical examples does Kennedy use to illustrate his preferred presidential model?

Kennedy invokes figures like Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, and Woodrow Wilson as exemplars of strong, effective presidents. He highlights their willingness to utilize the full extent of presidential power, exert legislative leadership, and champion moral causes, even at the risk of political unpopularity.

4. According to Kennedy, what are the essential roles of a modern president?

Kennedy outlines several key roles:

Chief Executive: A hands-on leader who actively manages government departments, resolves conflicts, and makes crucial decisions, particularly in foreign policy.

Legislative Leader: A president who proactively shapes legislation, collaborates with Congress, and uses their influence to ensure the passage of vital bills.

Party Leader: A president who actively engages with their political party, utilizing its machinery and leadership to advance their agenda and strengthen the democratic process.

Moral Leader: A president who inspires the nation, sets a high ethical standard, and mobilizes the public to address critical challenges and seize opportunities.

5. How does Kennedy view the relationship between the president and Congress?

While acknowledging the importance of Congress's legislative role and cautioning against executive overreach, Kennedy believes the president should actively lead and collaborate with Congress. He emphasizes that the president must be prepared to use all available resources to secure the enactment of crucial legislation.

6. What is Kennedy's stance on the president's role as a party leader?

Kennedy rejects the notion that a president should remain aloof from politics. He believes the president must embrace their role as party leader, engaging with the party machinery and working closely with party leadership to advance their agenda and strengthen the democratic process.

7. What is the significance of the Abraham Lincoln anecdote in Kennedy's speech?

Kennedy concludes by recounting Lincoln's unwavering commitment to the Emancipation Proclamation, even when facing internal opposition. He uses this story to illustrate the decisive and resolute leadership he aspires to embody as president.

8. What message does Kennedy aim to convey to the American people through this speech?

Kennedy seeks to persuade the public that the nation needs a strong, proactive president who will actively engage in solving national and international problems. He aims to differentiate himself from Eisenhower's approach and assure voters that he is the leader the times demand.

Here is a quiz it created:

The Presidency in 1960: A Study Guide

Quiz

Instructions: Answer the following questions in 2-3 sentences each.

According to John F. Kennedy, what is the central issue that should be addressed in the 1960 presidential campaign?

Why does Kennedy argue that good intentions are not enough to make a successful president?

What is the "restricted concept of the Presidency" that Kennedy critiques?

What does Kennedy mean when he says that the next president must be the "Chief Executive in every sense of the word"?

Why does Kennedy believe that the president must be an active legislative leader?

How does Kennedy contrast the legislative leadership styles of Theodore Roosevelt and Calvin Coolidge?

What criticism does Kennedy offer of President Eisenhower's approach to party leadership?

Why does Kennedy believe that Abraham Lincoln is a good example of party leadership?

How does Kennedy define the president's role as a moral leader?

What specific historical example does Kennedy use to illustrate the kind of decisive leadership he advocates for?

Answer Key

Kennedy argues that the central issue of the 1960 campaign is the Presidency itself. He believes the public needs to understand how a candidate views the role, powers, and limitations of the office.

Kennedy uses the examples of Woodrow Wilson and Warren G. Harding, both considered good men, to illustrate that good intentions alone are insufficient for presidential success. Different conceptions of the Presidency can lead to vastly different outcomes.

The "restricted concept of the Presidency" refers to a passive approach where the President primarily reacts to events rather than actively shaping them. Kennedy argues this approach is inadequate to address the challenges of the 1960s.

Kennedy believes that being "Chief Executive in every sense of the word" means actively engaging with complex problems, initiating action, and taking responsibility for the outcomes of his administration.

Kennedy argues that the President must be an active legislative leader to ensure the enactment of policies that meet the nation's needs. He contends that Congress should not dominate the executive branch nor should the President shy away from conflict with Congress.

Kennedy contrasts Theodore Roosevelt, who actively fought for his legislative agenda even at the cost of Congressional popularity, with Calvin Coolidge, who took a more passive approach and ultimately failed to advance key initiatives.

Kennedy criticizes Eisenhower's preference to remain above politics, arguing that a president cannot avoid politics and must actively engage with his party to advance his agenda and the democratic process itself.

Kennedy cites Lincoln's passionate engagement in politics, even closely following the results of state elections, as a model for how a president should actively lead his party.

Kennedy defines the president's role as a moral leader as one who goes beyond representing current sentiment and instead inspires the nation to meet challenges and achieve great ideals.

Kennedy uses the example of Lincoln signing the Emancipation Proclamation, despite potential backlash, to highlight the kind of resolute and decisive leadership he believes is essential for the presidency.

Essay Questions

Analyze Kennedy's vision of the modern presidency. What are its key characteristics? How does it differ from the "restricted concept of the Presidency" he criticizes?

Evaluate Kennedy's assessment of the presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Calvin Coolidge. How do their approaches to legislative leadership exemplify his broader arguments about the office?

To what extent does Kennedy's call for a "moral leader" in the White House align with the principles of a constitutional republic? Discuss the potential benefits and risks of such leadership.

Kennedy claims that "legislative leadership is not possible without party leadership." Analyze this statement, considering the relationship between the president, Congress, and political parties.

Compare and contrast Kennedy's conception of the presidency with another president or political thinker of your choice. How do their views converge and diverge? What might account for these differences?

Glossary of Key Terms

Chief Executive: The role of the President as head of the executive branch of government, responsible for enforcing laws and overseeing the administration of government agencies.

Legislative Leadership: The President's role in influencing the legislative process, proposing legislation, working with members of Congress, and advocating for the passage of bills.

Party Leadership: The President's role as leader of his political party, setting the agenda, mobilizing support, and working to elect party members to office.

Moral Leadership: The President's role as a national figurehead who sets a moral tone for the country, inspires citizens, and advocates for ethical principles.

Restricted Concept of the Presidency: A passive approach to the presidency where the president primarily reacts to events and defers to Congress or other actors.

Bully Pulpit: A term coined by Theodore Roosevelt to describe the presidency as a platform from which to advocate for policies and ideas.

Grand Alliance: A reference to the alliance of nations that fought against the Axis powers in World War II, emphasizing the president's role as a global leader.

Divided Government: A situation in which the presidency and Congress are controlled by different political parties.

Emancipation Proclamation: A presidential proclamation issued by Abraham Lincoln in 1863 that declared the freedom of slaves in Confederate-held territory.

Here is an outline of sources:

John F. Kennedy's Vision of the Presidency: A Table of Contents

Source 1: Excerpts from "All notes 12/11/2024"

The Presidency in 1960: A Study Guide

Quiz: A series of 10 short-answer questions designed to test comprehension of John F. Kennedy's vision of the presidency as articulated in his 1960 National Press Club speech.

Answer Key: Provides concise answers to the quiz questions, summarizing Kennedy's arguments regarding the importance of presidential leadership, the limitations of a passive approach, and the need for active engagement in legislative, party, and moral matters.

Essay Questions: Poses 5 in-depth essay prompts that encourage critical analysis of Kennedy's vision of the presidency, his assessment of historical presidencies, the role of moral leadership, and the relationship between the president, Congress, and political parties.

Glossary of Key Terms: Defines 10 essential terms related to presidential powers and roles, including "Chief Executive," "Legislative Leadership," "Party Leadership," "Moral Leadership," and "Restricted Concept of the Presidency," providing a conceptual framework for understanding Kennedy's arguments.

FAQ: John F. Kennedy's Vision of the Presidency

8 Frequently Asked Questions and Answers: Addresses key aspects of Kennedy's National Press Club speech, including his central theme, critiques of Eisenhower's approach, historical examples used, essential roles of a modern president, and the relationship between the president and Congress. This section provides a concise overview of Kennedy's arguments.

Source 2: Excerpts from "January 14, 1960 - Senator John F. Kennedy speaks at National Press Club, Washington, DC."

Fragment 1: This excerpt captures Kennedy's criticism of the Eisenhower administration's "restricted concept of the Presidency," highlighting the need for a more active and engaged approach to address the challenges of the 1960s.

Fragment 2: This segment emphasizes the need for a president who actively engages in the legislative process, contrasting this with a "casual bystander" approach that Kennedy deems insufficient.

Source 3: Excerpts from "Pasted Text"

Introduction: Sets the stage for Kennedy's argument by highlighting the importance of understanding a candidate's vision of the presidency and framing it as the central issue of the 1960 campaign.

Critique of the Eisenhower Administration: Kennedy critiques the "detached, limited concept of the Presidency" he observed during the Eisenhower years, arguing for a more active and engaged presidential role.

The Demands of the Times: Kennedy outlines the challenges facing the nation, both domestic and foreign, and argues that they require a strong, proactive president.

The President as Chief Executive: This section emphasizes the president's role as a hands-on leader who actively manages government, resolves conflicts, and makes crucial decisions, particularly in foreign policy.

The President as Legislative Leader: Kennedy argues for a president who actively shapes legislation, collaborates with Congress, and uses their influence to ensure the passage of vital bills.

The President as Party Leader: Kennedy rejects the notion of a president staying above politics and stresses the importance of engaging with the party machinery to advance an agenda and strengthen the democratic process.

The President as a Moral Leader: This section highlights the president's role as a national figurehead who sets a moral tone for the country, inspires citizens, and mobilizes the public to address critical challenges.

The Example of Abraham Lincoln: Kennedy concludes with a powerful anecdote about Lincoln's unwavering commitment to the Emancipation Proclamation, emphasizing the decisive and resolute leadership he aspires to embody as president.

Source 4: Excerpts from "The Presidency in 1960 (Remarks at the National Press Club) | Teaching American History"

Context and Introduction: Provides historical background and sets the context for Kennedy's speech, emphasizing the significance of his remarks within the broader history of the American presidency.

Kennedy's Speech Excerpts: Features key excerpts from Kennedy's National Press Club address, focusing on his critique of Eisenhower's approach, his vision for the modern presidency, and the importance of active leadership in various roles.

Discussion Questions: Poses thought-provoking questions that encourage readers to analyze Kennedy's conception of the presidency, his use of historical examples, and the relationship between the president and Congress.

Footnotes: Provides explanatory notes on historical figures and events mentioned in Kennedy's speech, enhancing understanding and facilitating further research.

This table of contents provides a detailed overview of John F. Kennedy's vision of the presidency as articulated in his 1960 National Press Club speech and related sources, offering insights into his beliefs about presidential leadership, the role of the president within the constitutional order, and the challenges facing the nation at the dawn of the 1960s.

But the truly dazzling product was the podcast.

Many people will use NotebookLM to help them write, or even let NotebookLM create their content. I watched one YouTuber use NotebookLM to produce a blog and podcast. I don’t want AI doing my work. I want to learn how to work at an AI level.

JWH