by James Wallace Harris, 7/22/25

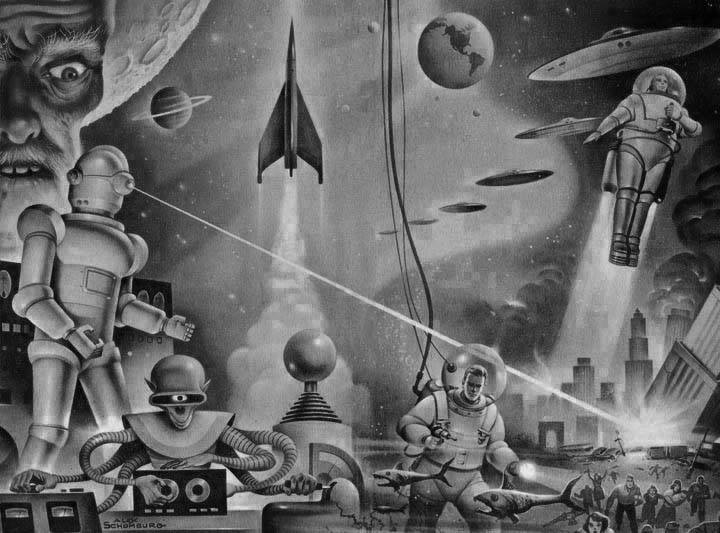

I’ve been amazed by how fanatical young people have become over their favorite pop cultural icons. My wife and I watch Jeopardy every day, and the clues are often based on successful pop culture franchises. Comics and young adult novels dominate, especially at the movie theater. Billions of dollars are spent by their fans, and children and young people often identify with certain characters.

At first, I thought all of this was new. The Beatles had worldwide fame, but I can’t think of any fictional characters that were as popular in the 1960s as those that have emerged in the 21st century. Star Trek and Star Wars fandoms began to evolve in the 1970s, but it wasn’t until the advent of the World Wide Web that they achieved pop culture universality.

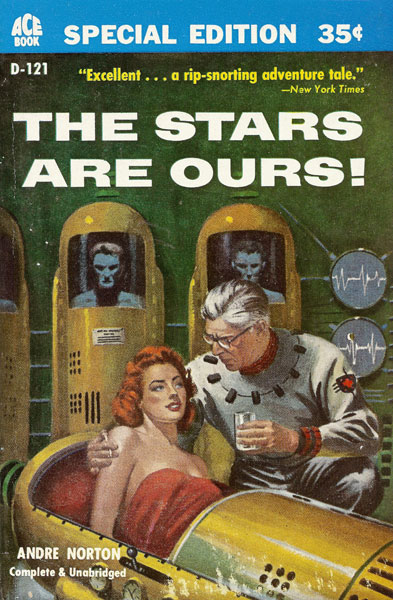

Many consider science fiction fandom the first. It began in the late 1920s and by 1939 had its first World Convention. However, we’re only talking hundreds. I considered myself a science fiction fan in junior high, but it wasn’t until the 10th grade that I met another fan in person. That was 1967.

Looking back, I realize it was YA novels that made me a fan, too. At seventy-three, I wonder if I would have had a different life if I had discovered the works of another author first.

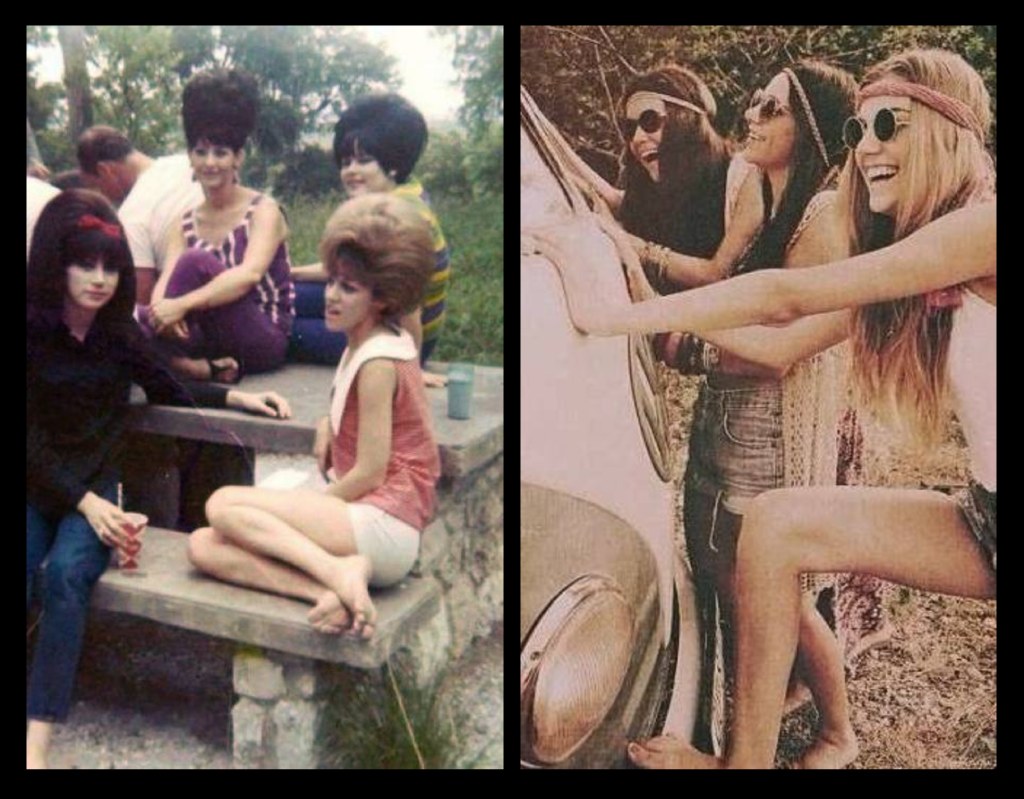

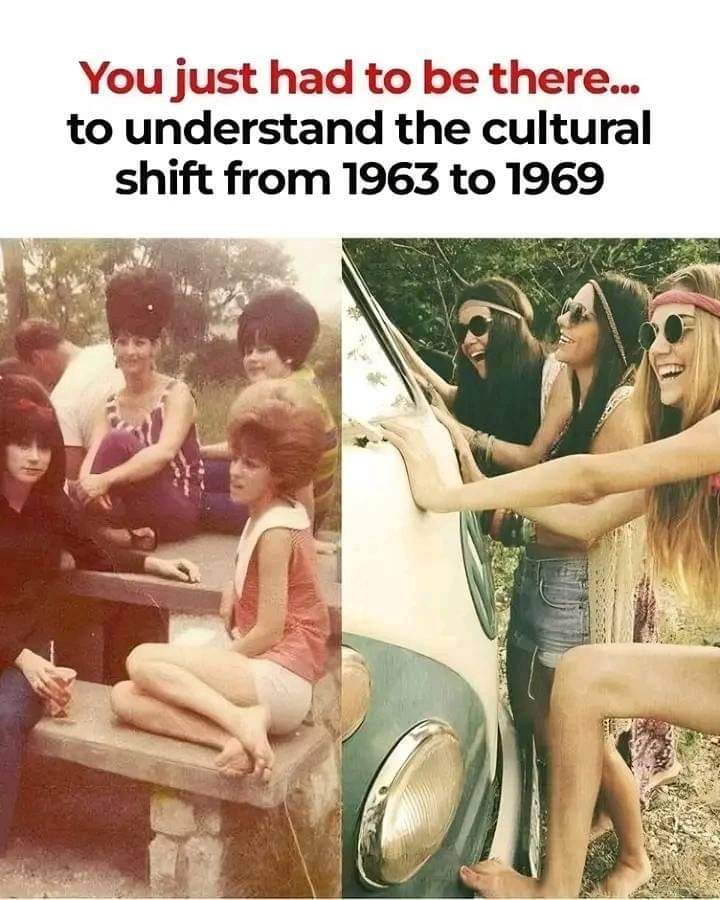

I realize now that reading books was my way of coping with the stress of growing up. Just after JFK’s assassination in November 1963, my family began to fall apart. In 1963-1964, I attended three different 7th-grade schools, and two 8th-grade schools, in two states, and lived in four different houses. My parents became obvious alcoholics, their marriage began to unravel, and my dad had his first heart attack. Somehow, I remained a happy kid.

Just before I turned thirteen, when I began the 8th grade in September 1964, I discovered the young adult novels of Robert A. Heinlein. They didn’t use the term young adult back then, but called them books for juveniles. Juvenile delinquency was also a common phrase back then. Before that, they were called books for boys. There were also books for girls. Gender roles were specific back then. This was when newspapers divided job listings into “Men Wanted” and “Women Wanted.”

Discovering Robert A. Heinlein and science fiction gave me a positive outlook on life and my future. I especially identify with the Heinlein juveniles. I remember at the time believing Heinlein would have a literary reputation similar to Mark Twain by the time the 21st century rolled around. That hasn’t happened. Heinlein is often shunned by modern readers of science fiction. I accept much of the criticism regarding his adult novels published after 1960, but I still embrace his young adult novels and other work published before 1960.

Charles Scribner’s Sons, famous for publishing Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Thomas Wolfe, first published the twelve Heinlein juveniles between 1947 and 1958. The Heinlein juveniles were highly regarded by librarians and schools. I discovered them because my 8th-grade teacher put them on her approved reading list. She required our class to read three novels, three magazine articles, and three newspaper articles every six weeks. If we didn’t, she lowered our grade one letter. If we read five of each, she raised our letter grade by one letter. I always read the five of each because I’m terrible at diagramming sentences and understanding grammar. That upped my C to a B each report card.

For over sixty years now, I have been grateful to this teacher. Sadly, I can’t remember her name.

I keep hoping YouTube book reviewers will read Heinlein’s juveniles and reevaluate their judgment on Heinlein. Over the decades, I’ve read memoirs by scientists, writers, and astronauts about how they loved the Heinlein juveniles when they were young, and the impressions the books made on them.

I’ve been meaning to reread all the Heinlein juveniles again and judge them without the influence of nostalgia. Has sentiment clouded my perspective? I fear my love of these books is similar to how people embrace religion when young. Ideas often brainwash us in youth, and it’s almost impossible to deprogram ourselves. Our species suffers from delusions. No one is free of being fooled by beliefs. For every individual, it’s a matter of how delusional.

At seventy-three, I’m taking a hard look at what science fiction did to my mind and personality. I’m starting with the Heinlein juveniles because I believe they were at the Big Bang of my becoming self-aware.

Before I got into science fiction, I consumed the Oz books by L. Frank Baum. I read an article in my thirties about how some libraries pulled the Oz books off their shelves because the librarians worried they gave children unrealistic expectations about life. At the time, I thought that was silly. However, I realized I had grown up with many unrealistic beliefs about life. At the time, I believed the Heinlein juveniles had made me more realistic. Four decades later, I know that was wrong too.

When I took computer programming classes, they taught us the term GIGO – garbage in, garbage out. Have all the pop cultural fantasies we’ve consumed caused our delusional adult beliefs? Humans have always been susceptible to religious fantasies. Haven’t we just replaced those with pop cultural fantasies?

I love the Heinlein juveniles. Why? If I understood why, would I still love them?

JWH