by James Wallace Harris

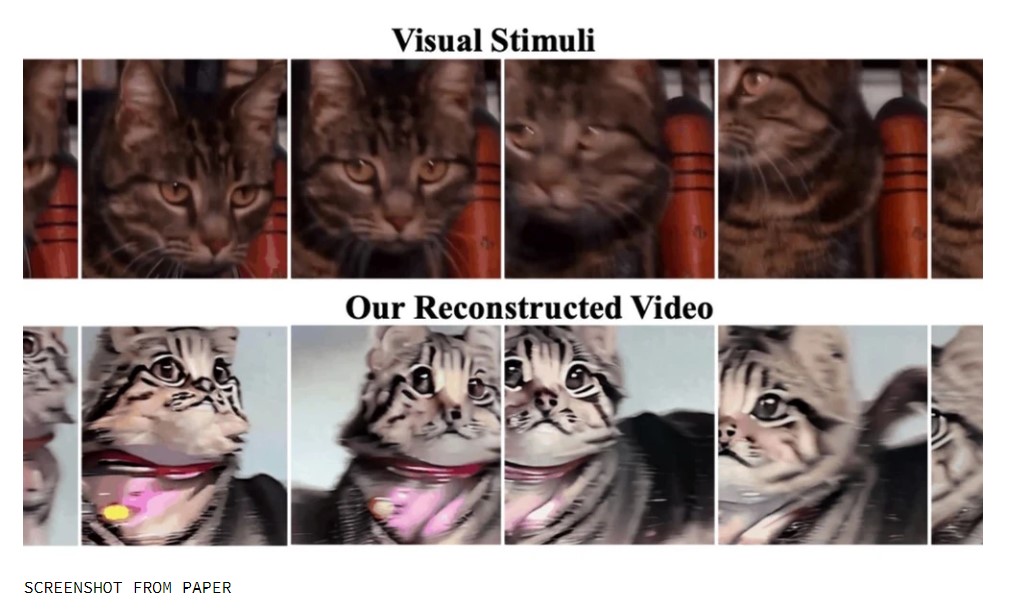

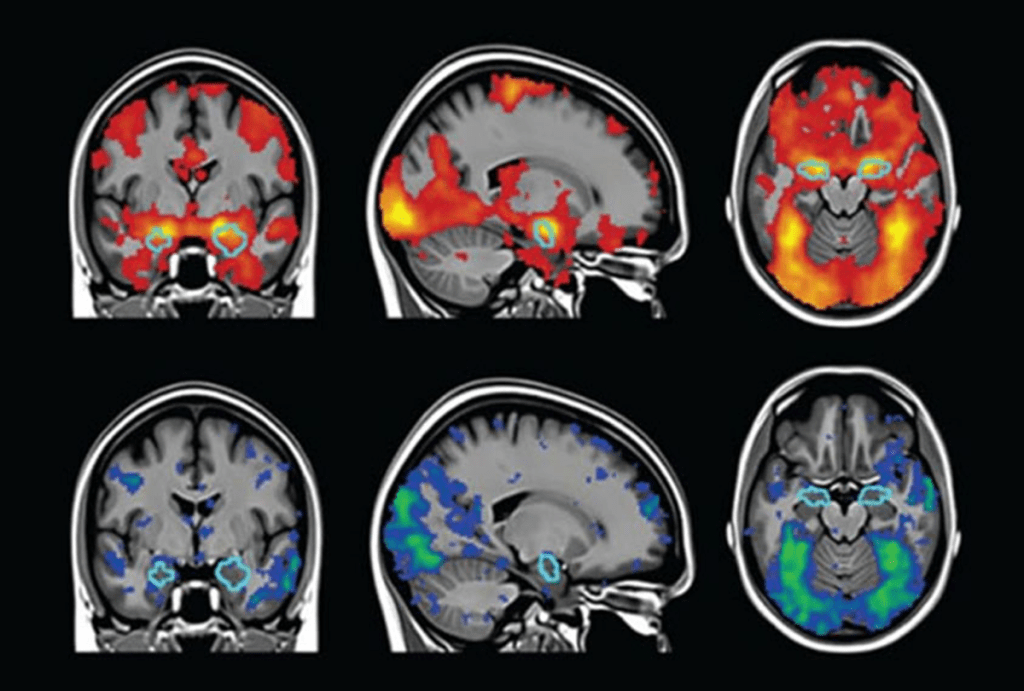

I believe recent developments in artificial intelligence prove that many of the creative processes we thought came from conscious actions come from unconscious mechanisms in our minds. What we are learning is computer techniques used to generate prose or images are like unconscious processes in the human brain.

The older I get, the more I believe that most of my thinking comes from my subconscious. The more I pay attention to both dreams and my waking thoughts, the more I realize that I’m very rarely making conscious decisions.

I might think “I am going to walk across the street and visit Paul,” but I have no idea how to make my body walk anywhere. But then, I’ve always assumed muscle actions were automatic. It was mental actions I believed were conscious actions. I used to believe “I am writing this essay,” but I no longer believe that. This has led me to ask:

Just what activities do we perform with our conscious minds?

Before the advent of writing, we did all our thinking inside our heads. Homer had to memorize the Iliad to recite it. Prehistory was oral. How much of thought then was conscious or unconscious? Have you ever read The Origins of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind by Julian Jaynes? I know his theories have lots of problems, but they do imagine what I’m thinking about.

How often have you worried over a problem, say a math problem, or a programming problem, and gave up, but then later, usually after a nap or sleep, the solution came to you? That’s the classic view of unconscious thinking. But even when we’re thinking we’re solving a calculus problem is it really being done at a conscious level? Are you consciously recalling all your math lessons over a lifetime to solve the problem?

How often when working on a Wordle or Crossword does the word magically come to you? But sometimes, we are aware of the steps involved.

In recent years I’ve developed a theory that when we work with pen and paper, or word processor or spreadsheet, or any tool outside our body, we’re closer to thinking consciously. Sure, our unconscious minds are helping us, but making a list is more willful than just trying to remember what we need at the store.

Writing an essay is more willful than woolgathering in the La-Z-Boy. Authoring a book is far more willful still. Engineering a submarine by a vast team of people is an even more conscious effort. Sure, it involves a collective of unconscious activity too, but a vast amount documentation must be worked out consciously.

I’ve written before about this idea. See “Thinking Outside Your Head.” That’s where I reviewed different techniques and applications we use to think outside of our heads.

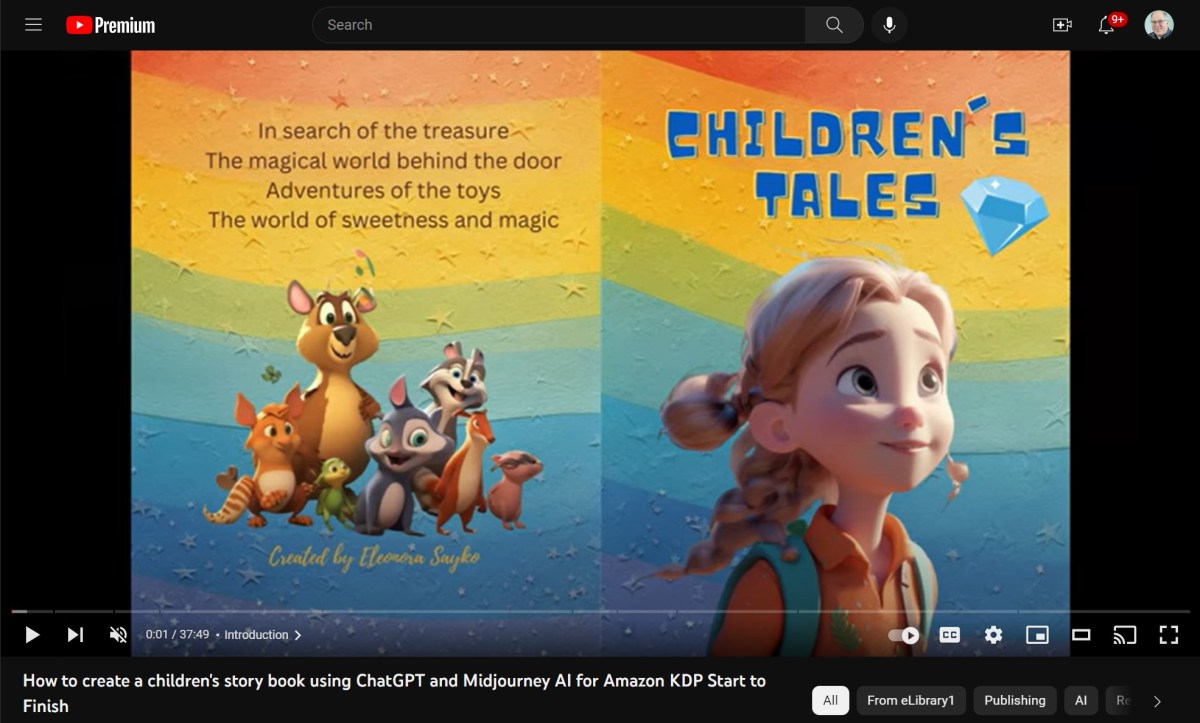

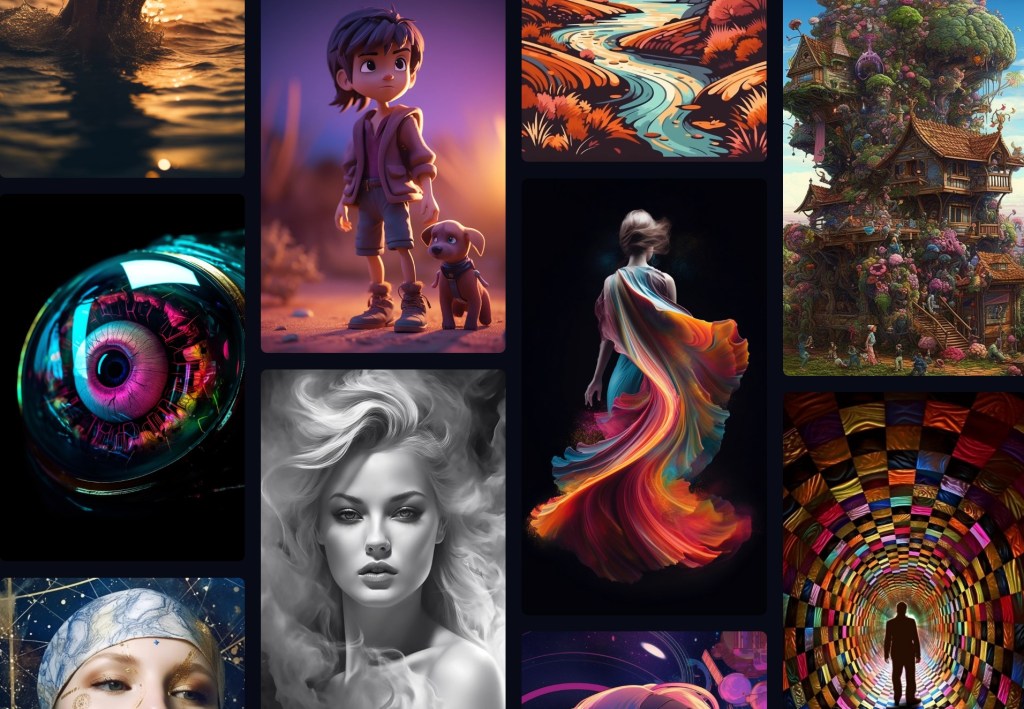

Many people want to deny the recent successes with AI because they want to believe machines can’t do what we do. That humans are special. If you scroll through the images at Midjourney Showcase, it’s almost impossible to deny that some of the images are stunningly beautiful. Some people will claim they are just stolen from human creativity. I don’t think that’s true.

I think AI developers have found ways to train computer programs to act like the human mind. That these programs have stumbled upon the same tricks that the brain evolved. Many great writers and artists often talk about their Muse. I think that’s just a recognition of their unconscious minds at work. What those creative people have learned is how to work consciously with the unconscious.

What some creative people are doing now is consciously working with two unconscious minds – their own and an AI. There is still a conscious component, the act of working with tools outside of our head. Where the action is, is that vague territory between the unconscious mind and the conscious one.

JWH