by James Wallace Harris, 6/24/25

I truly dislike vampires. Ditto for zombies. (Although I sometimes like ghosts.)

My short story reading group is discussing the stories from The Best Fantasy Stories from Fantasy and Science Fiction, edited by Edward L. Ferman. I must admit I also have a prejudice against fantasy in general. On the other hand, I want to participate in the group. I want to be positive in my comments. I don’t want to constantly whine about my annoyance with the common themes of the genre.

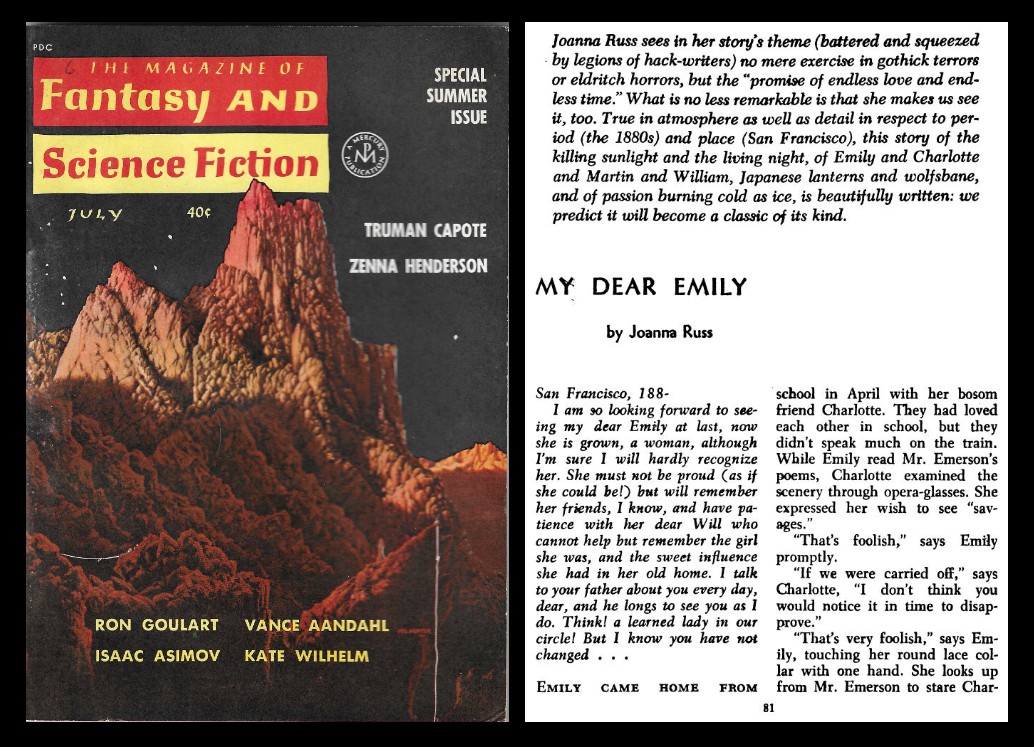

The second story up is “My Dear Emily” by Joanna Russ. It was first published in the July 1962 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. (You can read the story online.) F&SF provided my favorite genre magazine reading while growing up. I’m so fond of this periodical that I’ve collected an almost complete run of issues from 1949 to 1980. So, how can I be so prejudiced against fantasy?

I imprinted on science fiction when I first discovered reading. I consider science the only cognitive tool for understanding reality. Fantasy is based on magic and the love of the magical. Magic and science are polar opposites. I’ve never understood why people love fiction about beings that never existed. I will admit that science fiction is about beings that might exist, but are probably no more realistic than fantasy creatures.

My first impulse after reading “My Dear Emily” was to post this comment to the group: “Mediocre vampire story obscured by dense prose.” But would that be fair? Joanna Russ is a well-respected writer, even outside of science fiction. Within the genre, she is known for writing such classic feminist SF as The Female Man. Does “My Dear Emily” anticipate second-wave feminist themes in this 1962 story?

The story is set in 1880s San Francisco. Emily is returning from school in the east and bringing her friend Charlotte with her. Russ says, “They had loved each other in school.” Russ was a lesbian, but the story doesn’t appear to go in that direction at first, although in 1962, we might have been only expected to read between the lines. Emily and Charlotte do sleep in the same room.

Emily has returned to San Francisco to her father and Will, a man she is engaged to marry. Charlotte laughs at Emily’s endearing words about Will, and Emily wonders if God will strike her down for being a hypocrite.

However, Emily comes under the influence of Martin Guevara, a vampire. Why bring in the undead? We have the beginning of a good story with hints that Emily loves Charlotte but must marry Will in 19th-century America. My standard theory about why there are fantasy elements in literary stories is that it was easier to sell to genre magazines than get published in literary magazines. Literary magazines paid in free copies, but were usually a dead end for a story. “My Dear Emily” has been frequently reprinted in genre anthologies, earning additional payments and readers. In other words, would-be writers had a strong incentive to add fantasy or science-fictional elements to their stories.

Would I even be writing this essay, or have read “My Dear Emily,” if it hadn’t had a vampire in it? However, does Joanna Russ intend Martin Guevara to be meaningful in this story or just an in with the editor at F&SF?

Martin Guevara offers to get Emily out of her engagement to Will, but he exerts power over Emily, taking physical control of her. Emily already seems to know that Martin is a vampire. Did she know him before she left for school? And she leaves her house and finds me. How did she know where he lived?

On my second reading, this story seemed less murky, but it suggests things that aren’t explained. Emily tries to kill Martin with a silver cross, but he isn’t vulnerable to the power of that symbol. In fact, he isn’t affected by several of the classic defenses used against vampires. Martin tells Emily, “We’re a passion!” about his kind, and “Life is passion. Desire makes life.” He says desire lives when nothing else does.

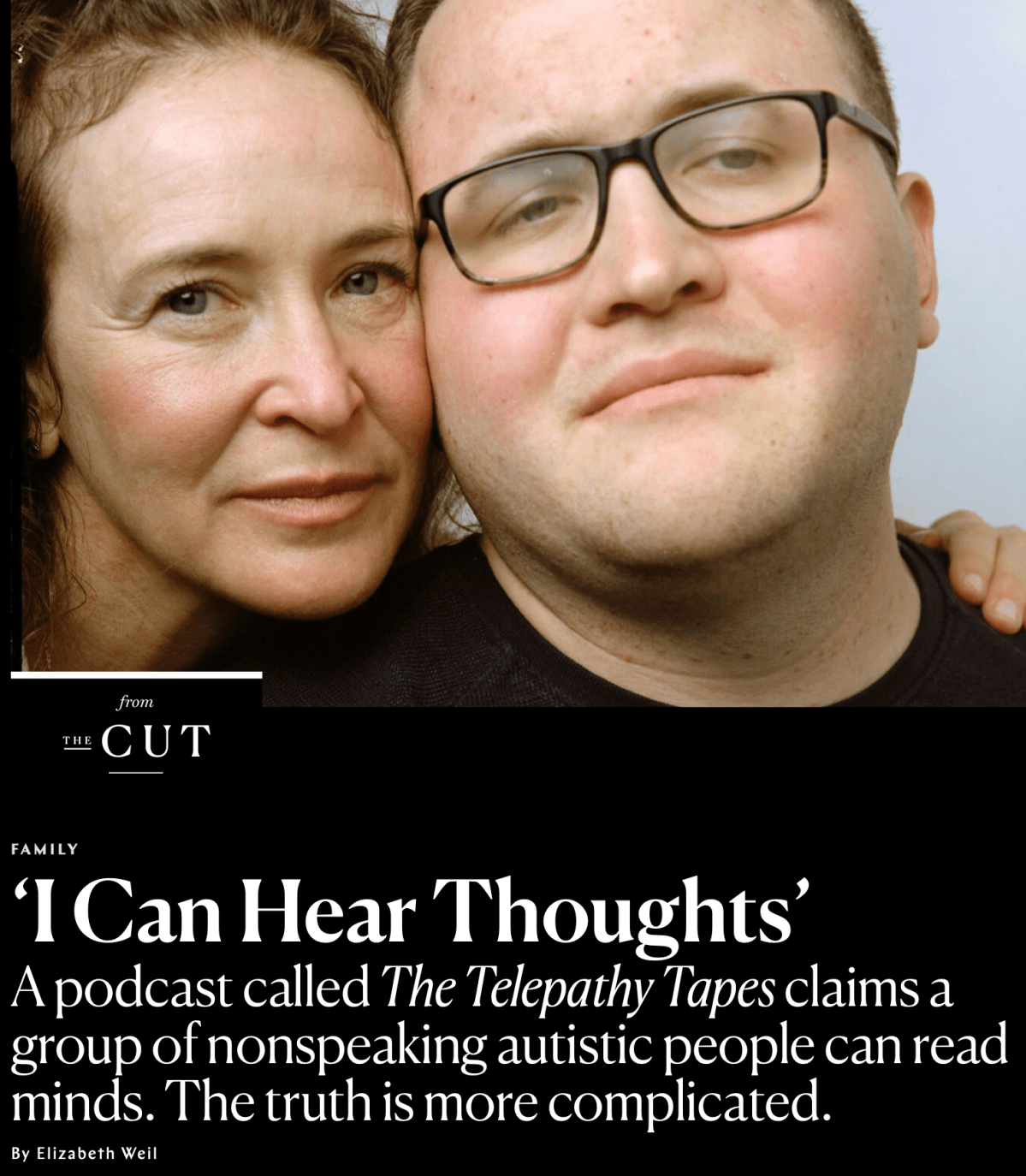

The story becomes more about vampirism. But is it really? Russ’s prose is far from explicit. Is the story a vampire fantasy or one of lesbian liberation? Are Will and Martin two poles of masculine power?

This story did not need a vampire. But to get published in F&SF, it did. Fantasy obscured the real intent of this tale.

Why does pop culture love the undead? Do they really add anything valuable to fiction? Or, are they just popular stock characters? At best, they might be symbolic, but isn’t that symbolism usually ignored?

JWH