by James Wallace Harris, 8/20/24

Sometimes you find yourself deep within the rabbit’s hole before you realize you’ve fallen into one.

I wish I had read the biographical entry for Sylvia Townsend Warner in Wikipedia before I read Lolly Willowes. It was her first novel, published in 1926. Warner was born in 1893 in Middlesex, England. She was greatly influenced by her father, a successful scholar, who died in 1916. Lolly Willowes is about Laura Willowes’ life after her father died. The story begins when Laura, called Lolly by her family, is twenty-eight, a spinster, who is forced to live with her brother’s family and take care of his children.

Warner was just five years older than Laura when she wrote Laura’s story, and unmarried. In the second part of the novel, Laura is forty-seven and lives a vastly different life. After Warner wrote Lolly Willowes she became involved with a life-long lesbian relationship. Warner authored many novels, many short story and poetry collections, worked in a munitions factory during WWI, became a communist, traveled to Spain twice during the civil war working with the Red Cross, and had a long productive life in several fields, including writing a biography of T. H. White. She died in 1978 at age 84.

In 1926 Sylvia Townsend Warner imagined it would take Laura twenty years before she could free herself from the roles society defined for her. Warner didn’t wait that long. I finished Lolly Willowes yesterday, and today I read the biographical piece in Wikipedia. It inspired me to order a biography on Warner by Claire Harman.

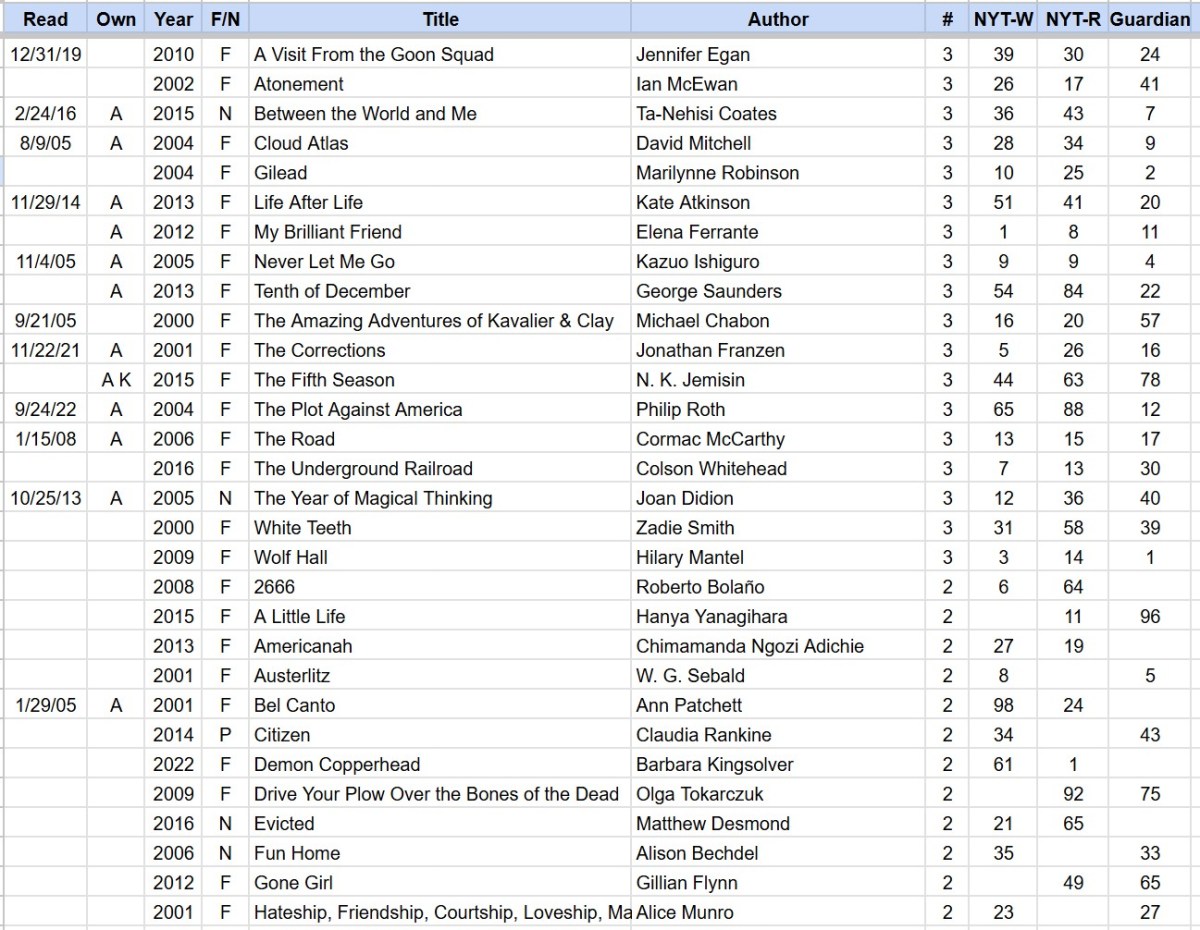

I bought Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner because the Kindle edition by NYRB (New York Review Books) was on sale for $1.99. NYRB is famous for reprinting forgotten classics. I often buy them when they go on sale, but what really sold me on Lolly Willowes is the blurb claimed it was the very first Book-of-the-Month Club selection. A quick peek at Wikipedia told me the novel was an early feminist classic, an international bestseller when it came out, and it was about witches and Satan. The book’s subtitle, “The Loving Huntsman” refers to the devil.

The NYRB edition is no longer available on Amazon, but since the novel is in the public domain, there are many editions available, including one for forty-nine cents. NYRB’s site still lists four novels by Warner, including Lolly Willowes, which does have a nice introduction by Alison Lurie.

Now, after all that build up, I’m not sure I can recommend this novel. Sometimes, forgotten classics are forgotten for a reason. The first half of this book tells us about Lolly’s upbringing and background. And it’s told rather than shown, meaning it’s a long narrative description. It’s not until Laura’s nieces and nephews grow up and have children of their own, becoming Aunt Lolly to a new generation, that she finally rebels. Laura moves to Great Mop, a small hamlet, to live alone. It’s here where she discovers she wants to become a witch and befriends the Devil.

At the beginning of the story we feel sorry for Lolly because she’s unmarried at twenty-eight. For most of the story we feel sorry for Lolly because for the next two decades she’s trapped as a live in aunt, in a role she doesn’t want. Then at forty-seven she defies everyone to go live on her own. It’s interesting that Warner has Laura gaining her freedom around the time of menopause. I am reminded of the sociological study, Sex and the Seasoned Woman by Gail Sheehy. Sheehy profiled women who felt that after menopause they no longer had to put husband or children first, and were finally free to pursue their own life. This fits with the novel.

Lolly Willowes came out in 1926, three years before Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. Late in Lolly Willowes Lolly tells the Devil, “It’s to escape all that–to have a life of one’s own, not an existence doled out to you by others….” Doesn’t that remind you of Woolf’s classic title?

It’s this impassioned speech that Lolly makes to the Devil that finally launches the novel into orbit. It’s a shame that it comes so late in the story. I even wonder if readers would benefit from reading it before starting Lolly Willowes. It might make all the rambling story that comes before it more powerful.

Here is that speech. Don’t read it if you think it will spoil the story. She is addressing the Devil.

“Is it true that you can poke the fire with a stick of dynamite in perfect safety? I used to take my nieces to scientific lectures, and I believe I heard it then. Anyhow, even if it isn’t true of dynamite, it’s true of women. But they know they are dynamite, and long for the concussion that may justify them. Some may get religion, then they’re all right, I expect. But for the others, for so many, what can there be but witchcraft? That strikes them real. Even if other people still find them quite safe and usual, and go on poking with them, they know in their hearts how dangerous, how incalculable, how extraordinary they are. Even if they never do anything with their witchcraft, they know it’s there—ready! Respectable countrywomen keep their grave-clothes in a corner of the chest of drawers, hidden away, and when they want a little comfort they go and look at them, and think that once more, at any rate, they will be worth dressing with care. But the witch keeps her cloak of darkness, her dress embroidered with signs and planets; that’s better worth looking at. And think, Satan, what a compliment you pay her, pursuing her soul, lying in wait for it, following it through all its windings, crafty and patient and secret like a gentleman out killing tigers. Her soul—when no one else would give a look at her body even! And they are all so accustomed, so sure of her! They say: ‘Dear Lolly! What shall we give her for her birthday this year? Perhaps a hot-water bottle. Or what about a nice black lace scarf? Or a new workbox? Her old one is nearly worn out.’ But you say: ‘Come here, my bird! I will give you the dangerous black night to stretch your wings in, and poisonous berries to feed on, and a nest of bones and thorns, perched high up in danger where no one can climb to it.’ That’s why we become witches: to show our scorn of pretending life’s a safe business, to satisfy our passion for adventure. It’s not malice, or wickedness—well, perhaps it is wickedness, for most women love that—but certainly not malice, not wanting to plague cattle and make horrid children spout up pins and—what is it?—‘blight the genial bed.’ Of course, given the power, one may go in for that sort of thing, either in self-defense, or just out of playfulness. But it’s a poor twopenny housewifely kind of witchcraft, black magic is, and white magic is no better. One doesn’t become a witch to run round being harmful, or to run round being helpful either, a district visitor on a broomstick. It’s to escape all that—to have a life of one’s own, not an existence doled out to you by others, charitable refuse of their thoughts, so many ounces of stale bread of life a day, the workhouse dietary is scientifically calculated to support life. As for the witches who can only express themselves by pins and bed-blighting, they have been warped into that shape by the dismal lives they’ve led. Think of Miss Carloe! She’s a typical witch, people would say. Really she’s the typical genteel spinster who’s spent herself being useful to people who didn’t want her. If you’d got her younger she’d never be like that.”

Warner, Sylvia Townsend. Lolly Willowes (New York Review Books (Paperback) Book 5) (pp. 149-150). New York Review Books. Kindle Edition.

Even though I bought the Kindle edition, I listened to the audiobook edition because it was part of my Spotify subscription. Hearing this speech came across far more dramatically than I can read it in my head.

I find it fascinating that Sylvia Townsend Warner could be so accepting of Lolly selling her soul to the devil. I must assume it was her way of saying how awful being confined by the traditional woman’s role was to her. Yet, Warner also portrays the Devil as Lolly’s master. Has she not traded one form of servitude for another? The biographical piece in Wikipedia also said that Warner wrote essays against the church.

Lolly Willowes does have a great deal of details about middle class life in England in the late 19th and early 20th century. I’ve always enjoyed those kinds of details about English life. There were many passages that reminded me of D. H. Lawrence. Unfortunately, I didn’t feel the story was consistently told as a singular work of art. And the novel seldom featured dramatic dialog.

Lolly Willowes is not a modern novel even though it came out in 1926. I felt it was closer in style to George Elliot, but Lolly Willowes lacks the depth of Dorothea Brooke, but then Warner’s novel is only five hours on audio, and Middlemarch runs around thirty-five hours.

If you’re into English novels, especially those written by women, then give Lolly Willowes a try. However, if you want a solidly fun book about an English woman on her own, reading Miss Buncle’s Book by D. E. Stevenson, which came out in 1934. It’s interesting how different women can be just seven years later.

I must admit, that the more I read about Sylvia Townsend Warner, the more likely I am to reread Lolly Willowes in the future. Like many books, multiple readings brings out depths missed with just one reading. I may have missed a lot.

JWH