by James Wallace Harris, Thursday, October 10, 2019

We make a lot of assumptions that we believe are true. That life will get better. That our children will have more than we did. That every kid should go to college and achieve all their dreams. That technology will solve our ecological problems. That humanity is destined to spread across space and colonize the galaxy. Overall, we think positive and assume we have unlimited potential. But what if these are false assumptions?

Today on Mike Brotherton’s Facebook page he linked to “Humans will not ‘migrate’ to other planets, Nobel winner says.” Brotherton is a professor of science and a science fiction author and he didn’t like what Michel Mayor said about our chances of interstellar travel. Whenever scientists, including some science fiction fans, question our final frontier destiny, many science fiction fans will quote Arthur C. Clarke’s famous Three Laws:

- When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

- The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.

- Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

It’s their trump card to play against any skepticism about an unlimited future. The common assumption among science fiction fans is we’re destined to colonize the galaxy and we’ll overcome all the obstacles of physics to do so. There are no limits to our hubris. I had faith in that space travel destiny when I was young but I’m losing it in my old age.

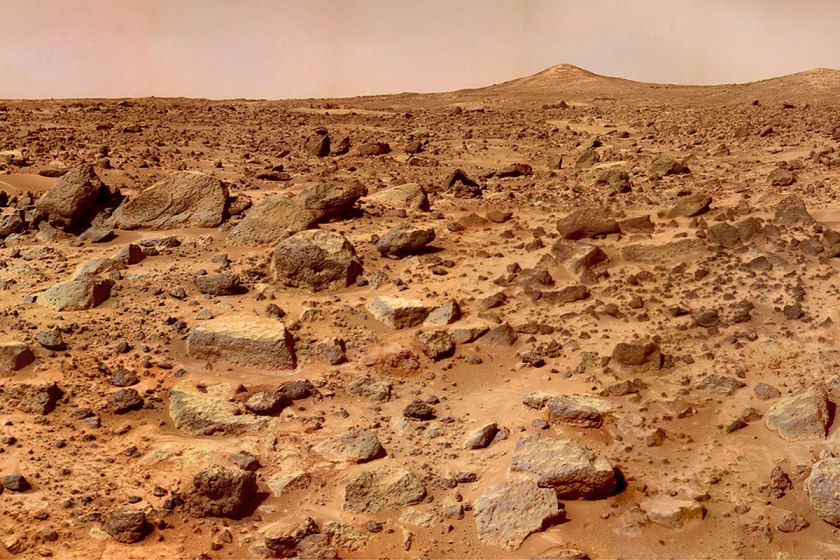

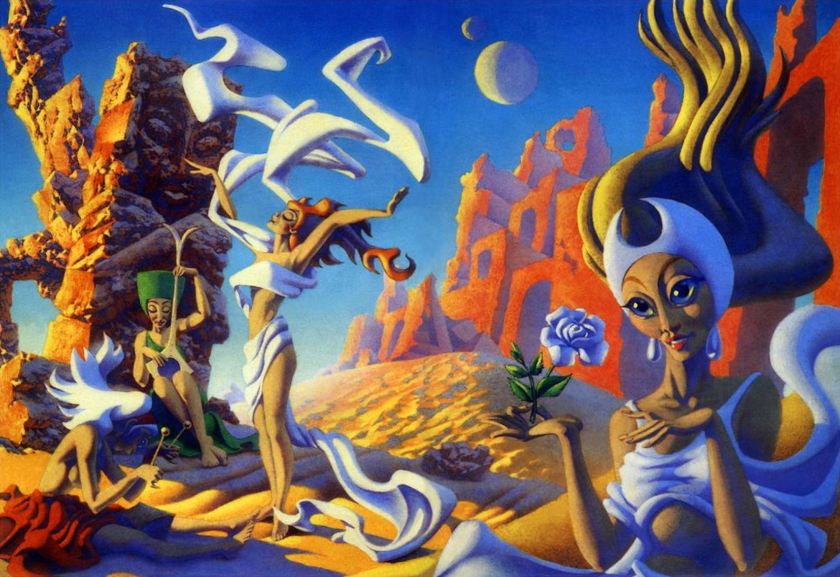

What if belief in a Star Trek destiny is delusional? What if our species is destined to always live on Earth, or maybe colonize Mars, a few moons, and build some space habitats? Why is it so important to believe we’ll eventually create a galactic civilization? Why is it so important to believe humans have unlimited potential when everything in this reality has limitations? Are science fiction fans behaving like the faithful believing in miracles?

The more we study the problems of space travel the more it seems an unlikely enterprise for biological creatures. However, space seems perfect for robots with artificial intelligence. Maybe our children won’t colonize space, but our digital descendants will.

If you study history it’s obvious that things constantly change. Even in my life much has changed. It’s hard to predict anything. I replied to Brotherton that I thought the odds are 99.99999% we won’t colonize exoplanets. He said, show my work. I wish I could. I’m not like Mayor, I’m not saying it won’t happen, but my hunch is it’s very unlikely. I’m not good at math, but I think my reply suggests 1 chance in 100,000,000. One in a hundred million events happen. It’s like winning a big lottery. So maybe, I was being overly optimistic. I probably should have added two or three more nines. All I can say is after a lifetime of reading about how hard interstellar travel will be, and how hard it is for the human body to adapt to an environment that it wasn’t designed for, my gut hunch is our species is destined to live out its entire existence on Earth. That means most space opera is no more scientific than Tolkien.

I feel that’s a crushing thought to science fiction fans. I assume it’s like Christians hearing from atheists that God and heaven don’t exist. I didn’t take to Christianity when growing up but embraced science fiction as my religion. I’m now becoming an atheist to my religion. However, I am getting old, and skepticism clouds my thoughts. I no longer believe free-market capitalism is sustainable. I no longer believe every kid should go to college. I no longer believe our children should be bigger consumers than we were. Our species is very adaptable. I think whatever changes increased CO2 brings we’ll adapt. I also believe our human nature doesn’t change, so I also expect we’ll keep consuming everything in sight even though it will lead to our self-destruction.

We’re about to reach the limits of growth by our current methods of growing. That doesn’t mean we won’t adapt to a new way of growing. If the world doesn’t need seven billion people with college degrees we’ll find out what it does need. If Earth can’t handle seven billion people all living the American standard of living, we’ll adapt to something new too. Humans might even adapt to living in microgravity or in lower and higher 1G gravity. We might even create life extension or cold sleep allowing for slow travel to the stars. It’s technically possible to get humans to another star system, but the odds are going to be tremendous. It’s not a given. I don’t think Mike Brotherton realized a 99.99999% chance is like a person winning a billion-dollar Lotto jackpot. It has happened.

Quoting Clarke’s Third law is no more valid than saying “Believing in Jesus will get you to heaven.” Faith does not change reality. Clarke’s laws aren’t science, but hunches, like my figure of doubt. From everything we know now, migrating to other planets is an extreme long shot. We can’t calculate the odds, but any figure we give should be daunting. Anyone assuming it’s 100% to happen is in just as much scientific statistical trouble as saying it’s a 100% chance it won’t happen.

I’m just a doubter. In my old age, I realize now that if science fiction wanted to be more positive, more enlightened, and more encouraging, it should imagine how our species could live on Earth without going anywhere. Even if a few of us go to the stars, most of us will stay here. Dreaming of greener pastures on the far side of Orion might not be our ultimate destiny. Maybe our final frontier is figuring out how to live on Earth.

JWH