by James Wallace Harris, Tuesday, July 17, 2018

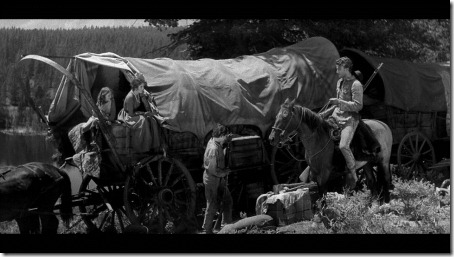

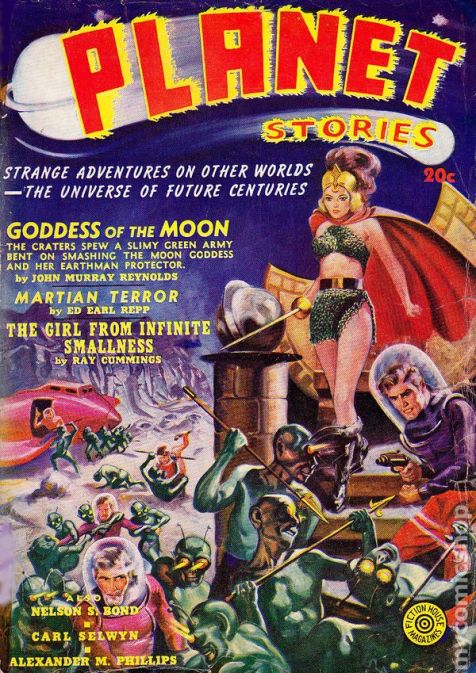

Did average Americans in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s believe that life, including intelligent beings, thrived on Venus and Mars, and maybe even the moons of Jupiter and Saturn? Folks of all ages read science fiction in the pulp magazines. Kids mostly enjoyed science fiction in newspaper strips and comic books, or watched science fiction serials like Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon at the movies. The 1950s began with several television shows aimed at kids about space patrols which adults enjoyed too. And in the late 1940s, America went nuts for flying saucers. I would assume science fictional ideas were quite popular, and people did believe life existed throughout the solar system. Most science fiction stories assumed Venus was a steamy jungle world, and Mars a cold arid desert world.

However, in all the classic MGM and Warner Brothers movies from those decades, and all the classic TV shows from the 1950s, I don’t ever remember any character talking about science fiction or life on other planets. It’s as if science fiction existed as a small subculture totally isolated from the rest of American pop culture.

I wonder if Americans in the decades before NASA really believe there was life on other worlds because science fiction from that era took it for granted there was. I doubt astronomers and other scientists encouraged those ideas. For 2018 I’ve been reading the best science fiction from each year starting with 1939. I’m currently on 1943 in my systematic reading, but I’ve been jumping ahead occasionally in my random reading. There is a sharp difference between science fiction written before NASA and after. We now know all the other planets and moons in our solar system should only interest geologists. There are a few biologists hoping they will have something to research on a few moons of Saturn and Jupiter.

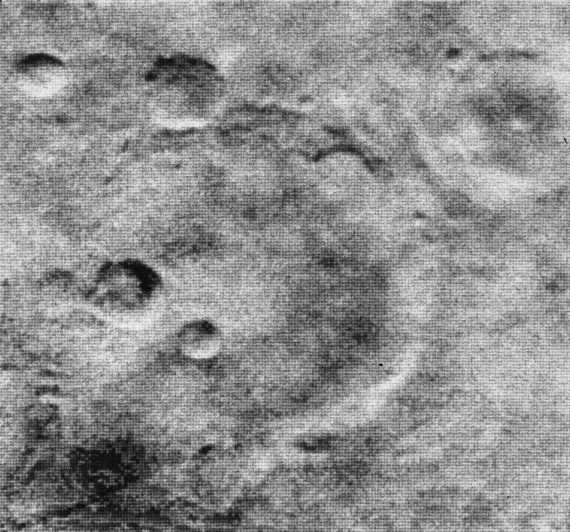

The robotic spacecraft Mariner IV flew by Mars on July 14, 1965, around 8pm EST. I have a memory of this event, but I don’t know the exact sequence of time, or if what I remembered was played out over days. I recall watching a special CBS news broadcast that interrupted regular television to show the flyby and first close-up photos of Mars. The grainy black and white pictures were devasting to my science fictional dreams because Mars looked just like the Moon, full of lifeless craters. There was no Old Ones living there (I had just read Stranger in a Strange Land and Red Planet by Robert A. Heinlein).

NASA had been established in 1958 but it was awhile before it began influencing science fiction. Sputnik (10/4/1957) and Explorer 1 (1/31/1958), the first satellites by Russia and the United States had made a tremendous cultural impact around the world. The Space Age had begun but it took a few years to begin gathering real data. Then in the early sixties, both countries sent up a series of space capsules. They were hardly the spaceships of science fiction. They were about the size of a VW Beetle, just large enough to cram one not-so-tall man inside.

I was 13 at the time of the Mariner IV flyby. I read a lot of science fiction, and I built Estes model rockets. I had been following NASA since Alan Shepard’s Project Mercury Freedom 7 flight on May 5, 1961. I grew up with a fantasy of space flight and the early reality.

Looking back now I can see how science fiction was changed by NASA. Before NASA science fiction fans, and maybe the public at large hoped the solar system was teaming with life. After NASA’s explorations in the 20th century, the solar system beyond Earth became a sterile bunch of rocks.

I now believe the pre-NASA science fiction era ran from April 1926 with the first issue of Amazing Stories and ended with “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” by Roger Zelazny in the November 1963 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. Although Zelazny’s story of Mars with intelligent beings wasn’t the last story to imagine such life on Mars, it’s how I like to remember pre-NASA science fiction ending. As the sixties progressed a New Wave of science fiction changed the genre. At the time we thought there was one new wave, but now I’m seeing two.

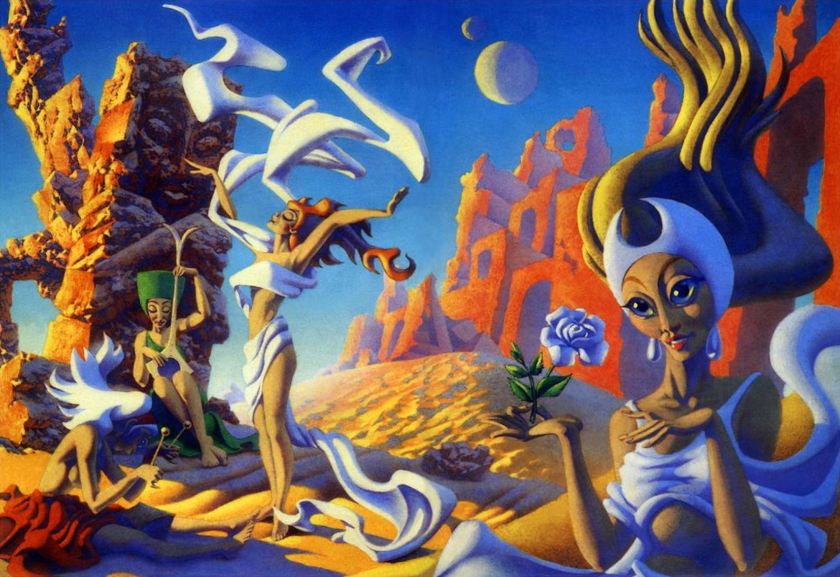

Yesterday I read “The Halfling” by Leigh Brackett in The Great SF Stories 5 (1943) edited by Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg. “The Halfling” first appeared in Astonishing Stories February 1943 and sadly had no interior illustrations even though the tale was extremely colorful and dramatic. It read like it should have appeared in Planet Stories because the story was about an interplanetary circus full of exotic animals from all over the system, with geeks who were hybrids of humans and intelligent creatures from Mars, Venus, and the moons of Jupiter and Saturn running the show. It’s strange that readers could accept so much diversity in space but not on Earth.

When I read old science fiction stories now, with the solar system teeming with lifeforms, it feels sad we’re all alone. I don’t know if the old science fiction writers invented all that colorful life because their plots needed it, or if they actually assumed life existed everywhere. I don’t think most folks want the NASA solar system. They want a Star Wars galaxy.

I often ask myself why do I keep reading the old science fiction? Hasn’t NASA invalidated those stories? I realize I’m like the faithful who hope for heaven living in a scientific world. Is waiting for The Day the Earth Stood Still to come true pretty much like waiting for The New Testament to come true? What if our respective dudes never show up?

I always choke up when I reread “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” because I still wish Mars had been like Edgar Rice Burroughs, C. L. Moore, Leigh Brackett, Robert A. Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, Philip K. Dick, and Roger Zelazny imagined.

While I read old pre-NASA science fiction I admire the creative imaginations of the writers. I like to think they were speculating and extrapolating, but maybe all they were doing is playing at make-believe. Most classical art is representative. Modern art invented what nature never produced. For a while, we thought science fiction worked to be representational of possible futures. Now it seems science fiction has been modern art all along, and NASA is now making the art of science fiction realistic again.

But I have to consider another angle. Pre-NASA science fiction covered the Depression, WWII, and the Cold War. These were stressful times. I read science fiction in my teens because it was a refuge from alcoholic parents that fought constantly and dragged my sister and I all over the country constantly changing our schools.

NASA space probes today bring back dazzling views of the solar system. They might not have found alien life, but those planetary vistas are gorgeous. The Milky Way galaxy in 2018 is a far more happening place than in pre-NASA science fiction.

I’m enjoying a nostalgic visit to pre-NASA science fiction. Maybe it’s a refuge from Donald Trump, climate change, mass shootings, polarized politics, environmental collapse, and the sixth mass extinction. And that’s okay.

JWH