by James Wallace Harris, Friday, October 26, 2018

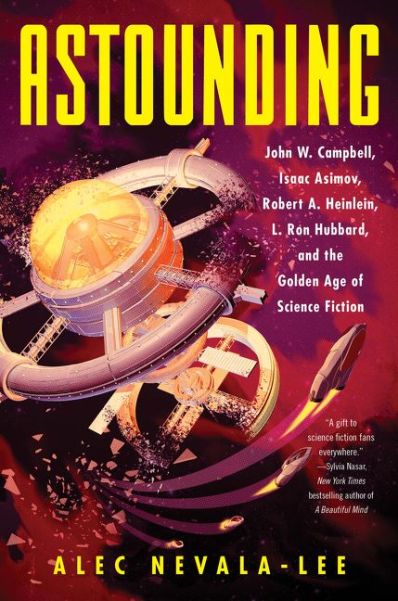

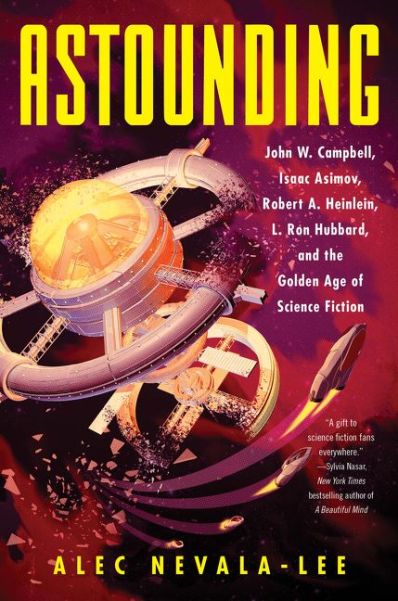

On October 23, 2018, the magazine Astounding Science-Fiction was remembered in two ways. First, Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series came in at #49 on the PBS Great American Read, and second, Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction by Alec Nevala-Lee was published.

On October 23, 2018, the magazine Astounding Science-Fiction was remembered in two ways. First, Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series came in at #49 on the PBS Great American Read, and second, Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction by Alec Nevala-Lee was published.

For a subgroup of the G.I., Silent and Baby Boomer generations, the Golden Age of Science Fiction was from 1939 to 1950, and mostly due to one magazine, Astounding Science-Fiction under the editorship of John W. Campbell, Jr. There was one other book in the PBS Great American Read where Campbell was the first editor to buy – that was Dune by Frank Herbert, which came in at #35. So, Campbell had two books in the top 50, not a bad legacy. Dune appeared in his magazine just after the name changed to Analog Science Fact & Fiction.

Alec Nevala-Lee’s new book, Astounding, isn’t the first history of the magazine, and I doubt it will be the last. As I listened to the audiobook edition I thought about all the ways writers have tried to tell the story of Astounding and the golden age of science fiction. Alva Rogers in Requiem for Astounding did an issue by issue overview. Arthur C. Clarke wrote a memoir about how the magazine shaped his youth in Astounding Days. And Alexei and Cory Panshin focused heavily on Astounding, Campbell, Heinlein, Asimov, and van Vogt in their Hugo winning book, The World Beyond the Hill: Science Fiction and the Quest for Transcendence. All those books focused on the stories. Nevala-Lee focuses on Campbell, Asimov, Heinlein, and Hubbard, giving us the biographical background to the editor and his three most famous writers.

There’s been plenty written about Asimov, Heinlein, and Hubbard, but other than tributes and collections of letters, I’m not sure how much has been written about John W. Campbell, and he is the real focus of Nevala-Lee’s book. However, his story is so intertwined with the magazine and his famous writers that Astounding is a history of the magazine and a biography of four men.

Reading Astounding was both rewarding and depressing. It’s depressing because we endure the painful deaths of all four subjects, but even worse than that, they all fall from grace. I’m not sure if I should reveal what they become. If I did, some would call it spoilers, but others might call them trigger-warnings. Let’s just say this is a tell-all biography where Nevala-Lee gives us the best and worst on each man. All four men were autodidactic know-it-alls. All four men were egomaniacs. Three, maybe four, had severe delusions of grandeur. All four were hard on wives and women, and at least two of them would have thrown out of pop culture if they lived during #MeToo times. One turns out to be white-supremacist and another started a religion and has been defied by his followers, even though Nevala-Lee makes it abundantly clear he was a pathological liar, and his church is often vilified and has a reputation of being a paranoid cult.

Despite all of this, Astounding is a valuable history book on an important era of science fiction. By combining the four biographies, Nevala-Lee shows us the wizards behind the curtain. Yes, in many ways, they were all humbugs, but in many other ways, they were genuine magicians. Campbell and all the writers of Astounding Science-Fiction created art that inspired a generation. Astounding Science-Fiction was essential to the evolution of the art form we know today as science fiction.

There has always been a problem calling 1939-1950 the golden age of science fiction because for many people it wasn’t. I’ve been systematically reading The Great SF Stories volumes 1-25 (1939-1964) edited by Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg. I’ve finished the first seven volumes, and I’ve got to say, many of the stories are forgettable. Nearly all the stories come from Campbell’s two magazines, Astounding Science-Fiction and Unknown. I’m sure these stories were mind-blowing back in the 1940’s, but there’s been much better science fiction written since using the same ideas and themes. In 1957 Peter Graham said in a fanzine called Void, that “The Golden Age of Science Fiction is twelve.” That deeply perceptive observation has been accepted as truth ever since. I turned 12 in late 1963, and the science fiction I discovered was published in the 1950’s. Some of it was reprints from Astounding in the 1940’s, and others were stories that appeared in F&SF, Galaxy, and IF, the Young Turks that usurped Astounding’s reign in the 1950’s, as well as original science fiction books that began being published that decade. Today, I generally think of the 1950’s as the golden age of science fiction, and I’m sure people younger than I feel the same way about the decade they first read when discovering science fiction.

This alternate view of the golden age of science fiction will probably limit the audience to Astounding by Alec Nevala-Lee, but it’s already the #1 book in Amazon’s Science Fiction and Fantasy section. Today it is quite common for young people, especially women and minorities, to dismiss older science fiction as being too white-male dominated from an unenlightened era. Nevala-Lee’s book will only reinforce those beliefs. However, I think it’s important to read this book. It does capture the ambitiousness of science fiction’s most ambitious proponents.

Science fiction changed dramatically in the 1980’s and 1990’s, and again this century. I routinely read science fiction stories from the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. Surprisingly, the ideas and themes remain consistent, but not the storytelling and characters. Science fiction authors have become much more sophisticated writers creating deeper and diverse characters. I see Nevala-Lee’s book as one piece in a very large puzzle. If you look for them, you’ll find plenty of books being written today on the history of science fiction. Most remain obscure and little read. I’m surprised that Astounding is getting all the attention it’s getting. Does it represent a tip of an iceberg of science fiction fans hungering to know more about the evolution of their favorite genre? Or, has all the science fiction fans from my generation suddenly become nostalgic for Astounding again?

I worry if younger science fiction fans read Astounding they may be turned off to 1940’s and 1950’s science fiction. All four men in Nevala-Lee’s book eventually come across as emotionally flawed, delusional, egomaniacal, and if not diagnosable with several DSM disorders, at least very nutty. Until the genre label “science fiction” emerged in the 1950’s, people would call it “that crazy Buck Rogers stuff.” I’m afraid the history in Astounding will only reinforce the crackpot reputation of science fiction.

This isn’t a criticism of the book, Nevala-Lee is just telling it like it was. But I believe readers need more context. I’m not sure people today have any idea what the psychological fallout the first atomic bombs, ICBMs, and Sputnik did to the citizens of the 1940’s and 1950’s. They all were looking desperately for answers to monumental existential threats. The stress was tremendous. Many thought the world was coming to an end. Psychiatry almost became a fad in the 1950’s, including experimental use of LSD under psychiatric supervision.

I’m not depressed that Nevala-Lee reveals how science fiction went nuts, but I wished he would have put its breakdown in the context of how everyone was going nutty back then. We look back with embarrassment to Campbell’s embrace of psychic powers, but a large segment of the country was doing the same thing.

I was born in 1951, so I grew up with the 1950’s. I remember my uncles raving about the psychic powers of Edgar Cayce and Jean Dixon, believing in the past lives of Bridie Murphy, excited by the multiple personalities of Eve, and dedicated followers the UFO nut, George Adamski. Nevala-Lee doesn’t mention how crazy America was in the 1950’s, so it seems Campbell is a standout nutter. He wasn’t. He was the mansplainer to mansplainers. He would pontificate to experts in their fields on their own subjects, telling them where they were ignoramuses.

I’ve also read other biographies of Heinlein as well as several biographies of Philip K. Dick, along with many interviews with SF writers of this era. It’s very hard to capture the crazy times from Hiroshima to Woodstock. And if you compare those times to our times, you’ll see that most people believed a lot of crazy crap by then. Of, sure, we still believe a lot of crazy crapola today, but those true believers in weirdness are far fewer now. And it is a fact that back then almost everyone had horrible prejudices and were unenlightened to equality. I’d like to believe society has evolved, and the percentage of crazy and prejudice people are down from those times. Of course, recent events suggest they were only hiding.

My one criticism of Astounding is by focusing on the biographies of Campbell, Asimov, Heinlein, and Hubbard Nevala-Lee didn’t convey the tremendous excitement and variety of the science fiction stories that Campbell published. And that probably wasn’t his goal. To most fans, Astounding Science-Fiction magazine was by far the best science fiction magazine of the times because of the stories. They didn’t care about the lives of the editors and writers. I hope future historians of this era include the other magazines like Amazing Stories, Thrilling Wonder, Startling Stories, Planet Stories, and Astonishing Science Fiction. I’m not sure Astounding deserves all of the attention and credit.

Alec Nevala-Lee’s book is one of a coalescing history. It is valuable because of its biographical slant. I wished he could have included more biographies of Campbell’s writers in his book, especially A. E. van Vogt, C. L. Moore, Clifford Simak, Hal Clement, Lester del Rey, Theodore Sturgeon, Ross Rocklynne, L. Sprague de Camp, and many more. Here is a list of all the stories that appeared in Astounding from July 1939 to September 1960.

Nevala-Lee’s book reminds me of the Beats. They were a literary subculture from the 1950’s that biographers can’t let go of. The Beat library keeps growing. I think the subculture of science fiction is attracting interest in the same way, and Alec Nevala-Lee is helping it by promoting the cult of the character. Heinlein, Asimov, Hubbard, and Campbell remind me of Kerouac, Cassidy, Ginsberg, and Burroughs. Over time, I believe the science fiction generation of the 1940’s and 1950’s will be remembered in biographies like The Transcendentalists, The Lost Generation, and The Beats.

Finally, I would like to also recommend The World Beyond the Hill by Alexei and Cory Panshin. It is coming to the Kindle next month and is currently just $3.99 for pre-ordering. And if you’d like to actually read copies of old Astoundings, click here.

JWH