by James Wallace Harris, 3/24/25

I woke up at 3:02am thinking about all the things I wanted to throw away. I’m only a moderately tidy person. For most of my life I let cleaning slide until I’m expecting company forcing me to clean up. But as I’ve gotten older I’m slowly becoming more anxious over disorder. For years I’ve tried to put everything in its place, but only after a certain amount of things have gotten out of place. Aging has caused that trigger number to grow smaller.

Something is possessing me. Since last September I’ve become obsessed over how untidy the yard has gotten. I spend an hour a day collecting leaves, limbs, logs, brush, rocks, and yard junk, puttig it out by the street. The pile grows and grows for weeks until the city comes by with a huge truck and giant claw carry it away. This photo is one fourth of my last pile.

My current pile is still small. I’ve got most of the big stuff cut down. I’m down to a thousand square feet of weeds I need to pull or dig up. But I’ve also unearthed an old brick floor of a greenhouse that’s been torn down and an old patio made from paving stones that I will need to dig up. Also, I’ve left the yard full of stumps that I need to dig up or have ground down.

Since I started all this yardwork I’ve begun dreaming of the day when I’ll have everything in the yard cleaned off and I can start designing the new yard. It’s caused me to develop a compulsion about clutter that’s now infecting how I feel when I’m in the house. I fantasize about getting a white fence to enclose the backyard. I crave a simple uncluttered landscape. That fantasy is now affecting how I feel about the house too. I want to declutter inside and make our decor a soothing simplicity. Of course, I have no landscaping or decorating skills, and neither does Susan. It’s just an urge that gnaws at me.

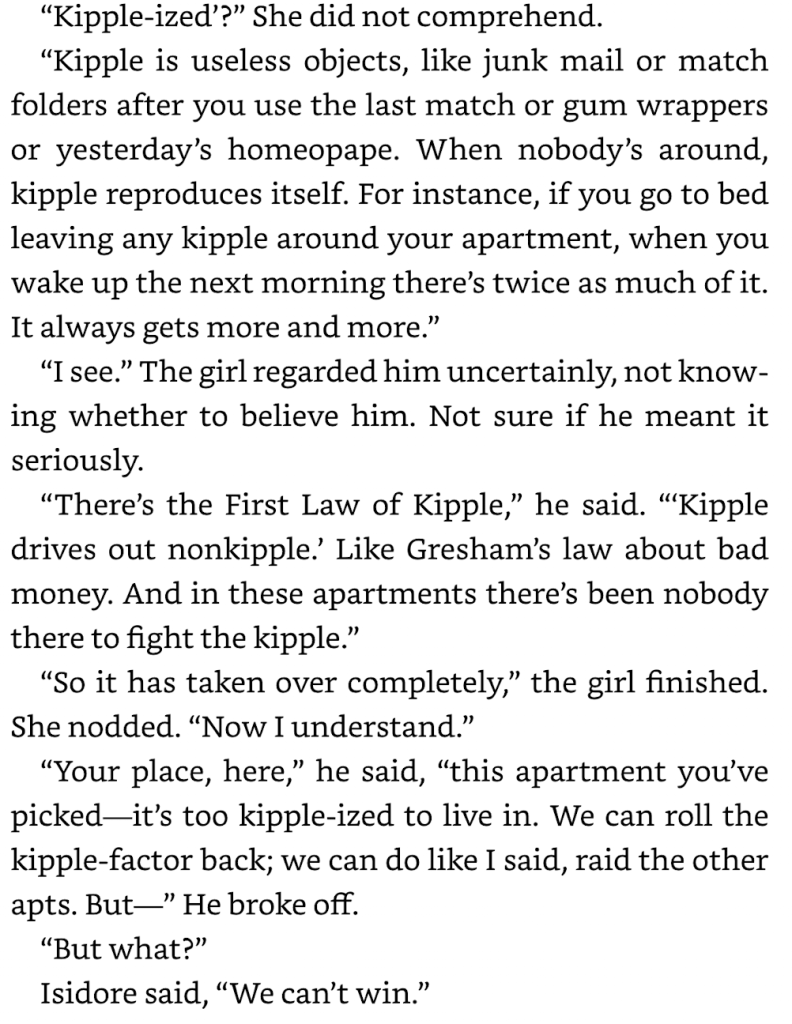

I feel like I’m becoming unhinged – like a character in a Philip K. Dick novel. In Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? one character describes Kipple to another:

Mother nature makes Kipple in the yard, Susan and I make Kipple in the house. If you ignore it, it reproduces, and we’ve ignored it for far too long. It’s time to battle the Kipple.

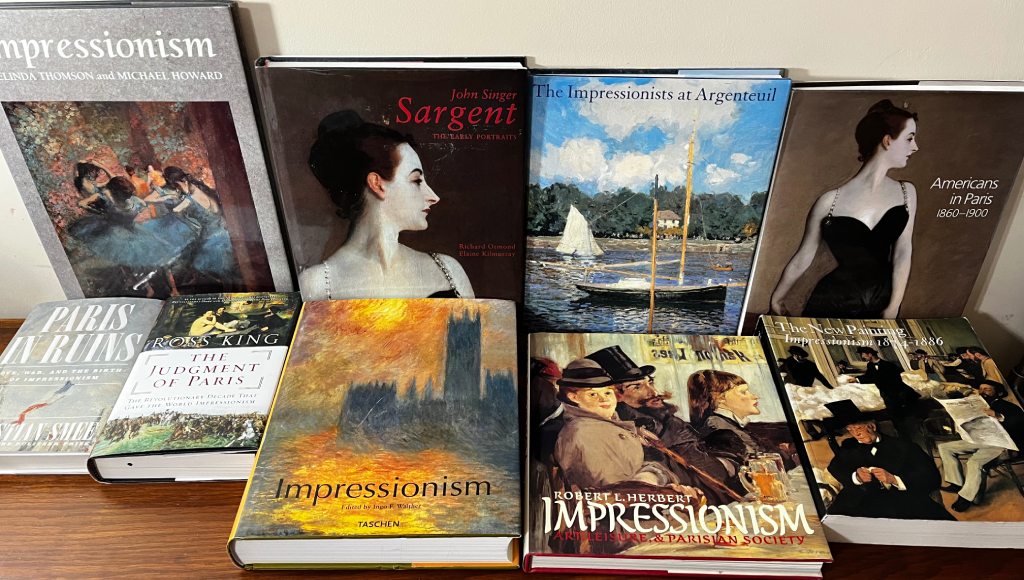

Last night during my period of insomnia I thought about all the Kipple I wanted to attack. I thought of all the ancient underwear in my chest of drawers that need to be thrown away, all the original boxes I’ve been saving in closets in case I need to ship something back that need to go into the recycle bin, all the old medicines that clog up the cabinet, all the machines I no longer use, the books I’ll never read, the bottles of cleaners that haven’t been used to clean anything this century, the clothes that have been on the same hanger for decades, and I realize I’ve got a case of spring cleaning fever.

But then I think about my computer and all my hard drives and the tens of thousands of files that clutter up my life. And all those photos on my iPhone that I never want to see again, and my bulging file drawers with paperwork that goes back forty-seven years of marriage.

Once you start thinking about clutter you see it everywhere. I think about that old joke about a guy who bought a new car whenever the ashtray got full. I fantasize about moving to a 55+ community and leaving all my Kipple behind.

Is this anxious state of mind caused by aging? I didn’t worry about an overgrown yard or a cluttered house when I was younger. Did I cause this when I decided to work in the yard? Does wanting to create order in one location cause you to want to create order everywhere? Susan is quite comfortable with clutter, so why am I so uptight about it lately?

Maybe my problem is psychological. Because the country is going down the drain and I can’t do anything about it, I’m compensating by trying to control a smaller territory, one within my power? That means aging wouldn’t be a factor. But then is that happening with everyone else? Do big crazy chaotic times inspire people to organize their little lives?

I don’t know what’s happening other than I get up every morning with an urge to throw things away. But there’s always so much more to throw away.

JWH