by James Wallace Harris, Sunday, May 12, 2019

It took me over ten years to graduate college, changing majors several times. I realize now that my problem was seeing the bigger picture of every topic. I never understood why I needed to learn what was required in each course. For example, The Modern Novel, a course I took for the English major I finally completed. Back in the 1970s, I couldn’t fathom why they called novels from the 1920s modern. Well, now in the 2010s, I do. I just read The World Broke in Two by Bill Goldstein. Goldstein chronicles how Virginia Woolf, E. M. Forster, D. H. Lawrence, and T. S. Elliot struggled in their personal lives to finish their most famous works in 1922. Each floundered in their efforts before finding new narrative techniques.

I now see the “modern novel” in a larger context, and I’m sure if I keep reading the history of everything from 1875-1930 I’ll expand that mental map even larger. Since I was an English major in the 1970s I’ve learned about the revolutions in art, music, philosophy, and other subjects in the early 20th century that add to that bigger picture. If I had taken courses in history, science, art, music, literature, engineering, medicine, etc. concurrently that covered the 18th-century one semester, then the 19th the next, and then 20th century, I would have understood how everything came together in the 1920s to be labeled modern. And that would have helped me comprehend the “post-modern.”

Concurrent to reading The World Broke in Two I’m also reading and studying the history of science fiction short stories. I’ve been reading these since the 1960s, and their evolution is finally coming together in multiple related ways. I realize now that I’m quite a slow learner when it comes to constructing the big picture in my head.

I remember back in high school and college feeling jealous how some of my fellow students always knew the answers. I assumed they studied harder than I did because I knew I didn’t study much. But that’s only part of the reason why they did better in school. I’m just now realizing they were also better at connecting the dots.

One of the big regrets in my life is not finding a passion while young to pursue with great effort and concentration. I knew success requires hard work, but the willingness to work hard requires drive and focus, and I never had that. I now understand that seeing the big picture is part of creating that drive and focus.

I’ve always been somewhat smarter than average, but never very smart. I had enough innate skills to get through school without studying much, but not enough cognitive insight to understand why I should study. I always saw school like the smaller image in the larger image above – a fragment of the whole that didn’t make sense.

Evidently, some people have a knack for seeing the synergy of details when they are young. We know this from the early works of successful people. It must be a cognitive skill like a sense of direction, spatial awareness, or conceptualizing in three-dimensions, but with data and ideas.

I know what I’m saying is vague, but then I’m trying to describe something I’m challenged at understanding. I only have a hint of its existence. I wonder if its a skill they can teach young kids? However, I also wonder if the way they teach subjects in school actually works against gaining this skill. Because schools divide up learning into thousands of lessons we’re trained to memorize individual facts, and not how those facts make patterns. Of course, pedagogy might have changed since I went to school a half-century ago.

I’ve often wondered if in each school year they should teach students the history of reality from the Big Bang to now so they see how all areas of knowledge evolved together. Of course, in pre-K years teachers would have to be very vague by telling kids the biggest generalizations, but with each successive year refine those details. I wonder if kids learned to see how knowledge arose from previous knowledge it wouldn’t help reveal bigger pictures of how things work.

JWH

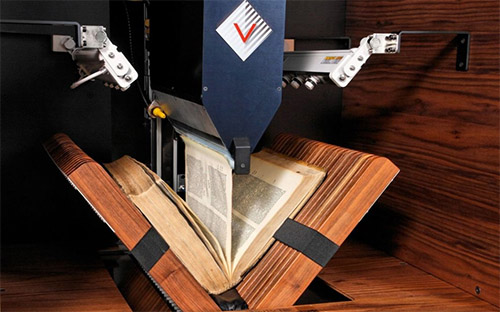

Most of us do not have evidence that will matter to historians, but you never know. And even if we did, how do we pass it on? If you’re a famous person you can donate your papers to a library. One thing us ordinary folks can do is to share photographs with relatives, or anyone who is pictured in the photographs. I have some old school yearbooks that I’m going to scan and upload to the Internet Archive.

Most of us do not have evidence that will matter to historians, but you never know. And even if we did, how do we pass it on? If you’re a famous person you can donate your papers to a library. One thing us ordinary folks can do is to share photographs with relatives, or anyone who is pictured in the photographs. I have some old school yearbooks that I’m going to scan and upload to the Internet Archive.