by James Wallace Harris

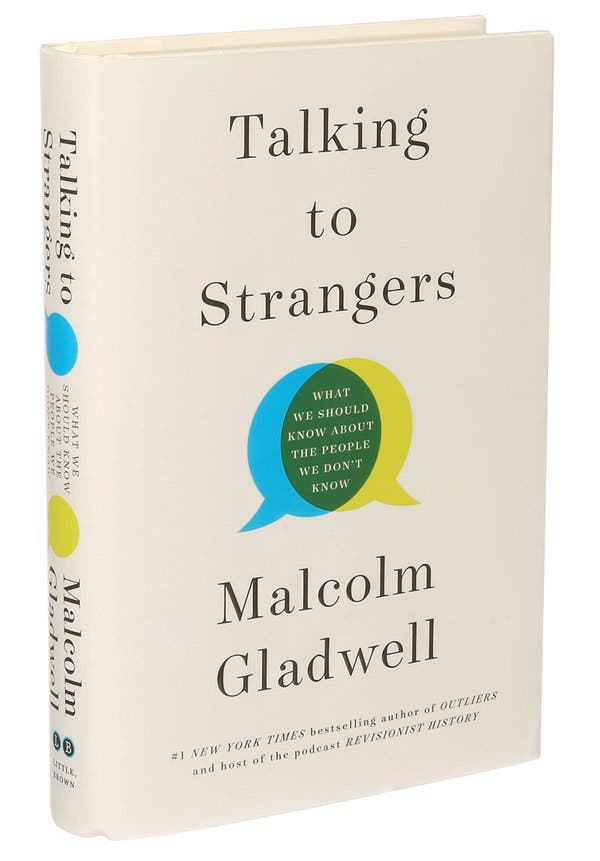

Basically, my blog is where I write what I think. I polish my essays to be more readable, but I’m too lazy to be more ambitious. Blogging is piano practice for writing but seldom produces professional-level writing. Blogging improves writing skills, exercises the brain to think clearer, but is too casual to produce art. Lately, whenever I read an exceptional essay I feel both envy and regret. Envy for craft, and regret for laziness. It’s time to up my ante.

I recently wrote about rereading Brave New World fifty years after first reading it in high school. Then I read “BRAVE NEW WORLD Revisited Once Again” by the science fiction writer Thomas M. Disch in On SF. I was amazed by how much better Disch had done with the exact topic. He opens with:

| Just fifty years ago, at the dawn of the new era that dates from the death of Henry Ford, a young, half-blind, upper-class Englishman published a novel destined to become—along with Orwell’s 1984—one of the two most enduring prophetic visions of the future ever to clatter from the typewriter of man. The novel was Brave New World, its author Aldous Huxley, and the vision was of the Jazz Age gone to heaven. Anything goes in A.F. (After Ford) 632, but what goes particularly well are those two pillars of the affluent society, sex and drugs. What has been eliminated from that society as being subversive and destabilizing is: family life, passionate love, social nobility, and any art but the “feelies, ” fashion design, and dance music. Here’s a sample of the song lyrics and the lifestyle of A.F. 632:

Orgy—porgy, Ford and fun, |

I realized this was a complete lesson in writing. Here’s my opening paragraph:

| I first read Brave New World in high school back in the sixties. Rereading it again in 2020 reveals that it was entirely over my teenage head. I doubt I got even 5-10% of Aldous Huxley’s satire. Although I expect high school and college students of today have both the education and pop-culture savvy to understand it better than I did, it’s really a novel to read after acquiring a lifetime of experience. When I first read Brave New World I was already mass consuming science fiction so it was competing with shiny gosh-wow sense-of-wonder science fiction. I remember liking Brave New World in places, especially the free sex and Soma, but I thought the story somewhat boring and clunky. |

My paragraph was more about me than Brave New World. I feel Disch and I are both trying to get people to reread Brave New World but his lead-in is a better salesman. His paragraph is dense with details about the book, while mine has too many details about myself. Should I even be the subject? My intent was to convince people the book deserves a second reading by my experience, but I could have done that without talking about myself.

Do visitors to this blog want to know about me or the topic of my discussion? Blogging is intended to be personal, and I have a number of followers for this blog, but the essays with the most hits are from people searching Google on a specific subject. Those readers aren’t interested in me. I could have written my first paragraph without any mention of myself and still provided the same data.

I consider this blog, Auxiliary Memory, to be my personal blog and Classics of Science Fiction to be a reference site. Maybe I should use a different style of writing for each.

Information is the key. When people read, people either want specific information or entertaining information. And web readers want quick information. I’m a wordy bastard. This essay is already longer than what the 99% want to read. But I haven’t covered my topic. I could describe a dozen insights I’ve learned from Disch’s essay and make this post 3,000 words long. Or I could put each insight into a different post.

If information is the key, then information density is the essence of great writing. I’m still impressed by how much Disch conveys about Brave New World in his first paragraph. I believe his summary says even more in fewer words.

| My final quarrel with the book is one of emphasis from my first reading. I’ve always had a sneaking fondness for the world Huxley invented. I know I’m supposed to disapprove. But I would like to try soma just once, and I wouldn’t say no to a night at the Westminster Abbey Cabaret dancing to the music of Calvin Stopes and his Sixteen Sexophonists. The lyrics of the songs may be sappy, but I’ll bet they’ve got a good beat. As for the feelies, I suppose the plots are pretty simpleminded, but any more so than Raiders of the Lost Ark?

This is not to endorse all the sinister theories of Mustapha Mond, only to suggest that fun’s fun, and that some of the targets of Huxley’s satire are mean-spirited, insofar as he is making a case against pop culture, sexual candor, and the consumption of alcoholic beverages. Relax, Huxley. You worry too much. Have a gram of Tylenol. Things could be worse. This might be 1984. |

Disch’s reading reaction that Huxley’s dystopia is alluring is close to mine. Disch combines story description with story reaction into the same sentence where I separated them into different paragraphs.

My envy of Disch’s writing inspires me to work harder, but it also makes me ask myself a lot of psychological questions about why I want to write. Blogging and other social media appeal to our urge to express ourselves. On many levels, I worry that’s appealing to our ego and vanity. Of course, we also call our activities on social media sharing. But what exactly are we sharing? Ourselves, information, promotion of cool things, memories, passions — the list goes on and on. When a writer produces a work to be read, they are also asking readers to use up some of their time.

The best thing I learned from my six weeks at the Clarion West writers’ workshop was “Great writing is the accumulation of significant detail.” I believe what I learned from my recursive reflection between these two pieces is: “Great writing is the accumulation of significant detail that wastes the least time for the reader.”

That’s a single lesson at one recursive turn. With another cycle, Disch’s prose sparkles for me because I just reread Brave New World and all his allusions resonated. That wouldn’t be true for people who haven’t read the book. That insight reflects back again, and I see I admire Disch’s essay because we both reread Brave New World late in life after first reading it when young. Seeing that lets me know great writing isn’t always in the prose but in the sharing. But that reveals the limits of finding the right reader.

I could keep going, but after the 1,178th word, I believe I spent enough of your time.

JWH