By James Wallace Harris, 10/19/25

At thirteen, I read books entirely differently than I do now at seventy-three. I think everyone does, but it’s not apparent why. Our memory gives us the illusion that we’ve always been the same person. But if we think about it, there is plenty of evidence that we couldn’t have been.

I’ve been thinking about the difference between my younger reading self and my older reading self while writing a review of The Foundation Trilogy by Isaac Asimov for my other blog. Every so often, I reread a book I read as a teenager. For some books, it’s a nostalgic return to a familiar, comfortable place. For most books, it’s just vague recollections.

My first realization from trying to reconstruct my reading mind at age 13 was to remember that I read very fast. I consumed books like potato chips. Reading was like casually watching TV. Words just flowed past my eyes, and I didn’t always pay attention to every word. I just read to find out what happened.

I have a fond memory of reading The Foundation Trilogy, but a limited one. I liked the idea of a galactic empire in decline. However, the only chapter I can remember is the first one, “The Psychohistorians.” It wasn’t until decades later that I learned that the trilogy was a fix-up novel based on nine stories running from short stories to novellas.

Thinking about it now, I realize that most of the ideas in the book didn’t mean much to me at 13. I had not studied or read about the Roman Empire, Asimov’s inspiration. Actually, I probably didn’t know what an empire was either. Nor did I understand all the references to nobility, aristocracy, and politics.

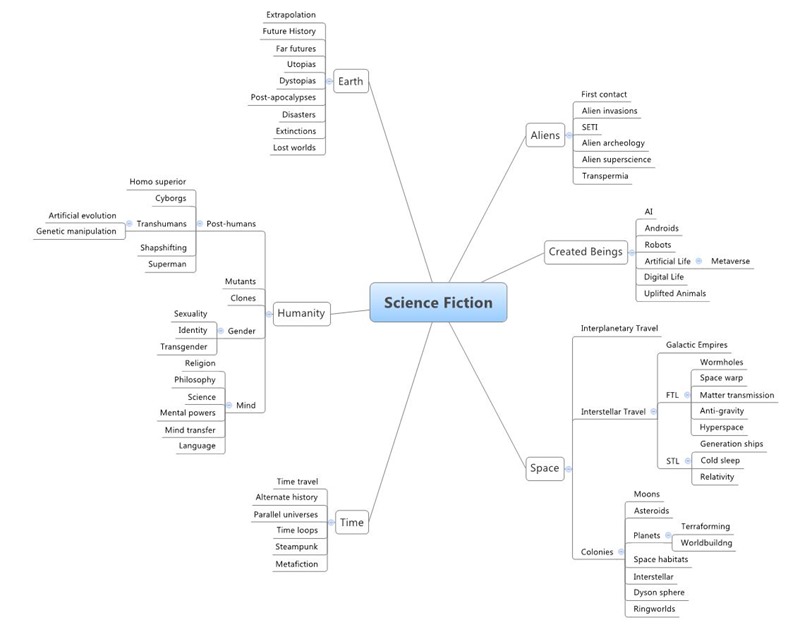

As a teenager, I mostly read science fiction books. I did read some popular science books too. My awareness of the world and my vocabulary were limited. However, I didn’t know that. And I wasn’t the kind of person who looked up words I didn’t know. What’s weird is that I was a kind of know-it-all.

One way to judge my teenage brilliance was that my favorite TV show at the time was Gilligan’s Island. When I catch that show today, I can only assume I was brain-dead back then.

I’ve tried to reread The Foundation Trilogy twice now. The first time was in 2015, and now in 2025. In both cases, I could only finish the first book of the trilogy. I loved the first story, but with each additional story, I detested them more.

At first, I thought that Asimov’s most famous books were just bad. But I’ve known people smarter than me, and just as old, who say they still loved the Foundation series. One woman in our reading group said the Foundation stories were a great comfort to reread. And I recently heard that twenty million copies of the series have been sold.

Not only was my current reading self different from my younger reading self, but I’m out of step with millions of readers. This got me thinking about the different modes of reading.

I think the most basic mode is just to let fiction flow over you. You read whatever pleases you. And you don’t think about why.

Then, as we age, we become more judgmental. We learn more about life and reading. We develop a process of natural selection by rejecting what we don’t like. We don’t think much about why we don’t like what we don’t like. We just evolve into a reading machine that knows what it likes.

Two other reading modes are: English teachers or literary critics. These are very critical modes, and often they take the fun out of reading. I think as I’ve gotten older, my reading habits have taken on a bit of these two modes. While in them, it’s all too easy to shoot Asimov down.

However, I’ve discovered another mode recently when I read “Foundation” for the fourth time. “Foundation” was the first story published in the series in 1942. While reading this story yet again, I kept admiring Asimov for where he succeeded and not where he failed.

In my rereadings, I’ve always come to the series wanting to love it. And I’ve always been disappointed by how much I didn’t. But with this reading, I worked to think like Asimov. What was he trying to do, and how did he go about doing it?

I’m in the process of documenting this for my other blog, Classics of Science Fiction. I’m writing this now because the other post is going to take a long while to complete.

I never would have put this much effort into reading a story when I was a teen. Or any time before I was 73.

One reason I dislike this story in recent years is my skepticism. I don’t believe humans will ever travel to the stars, much less form a galactic empire. Another reading mode I’m trying to develop is to read with the mind of a person from when the story was first published.

Trying to read like Asimov thought and how science fiction fans felt in 1942 is difficult. I’m reminded of Samuel R. Delany’s concepts of simplex, complex, and multiplex that he described in his story Empire Star. I started out as a simplex reader and eventually evolved into a complex one. Now I’m moving into a multiplex reader.

Multiplex thinking often involves holding contradictory viewpoints. I really dislike the Foundation stories. But if I work at it and look at them in just the right way, I can like them too. It’s hard. It’s a Sisyphean struggle learning to admire something that triggers so many annoyances, but I’m working on it.

JWH