by James Wallace Harris, 3/21/23

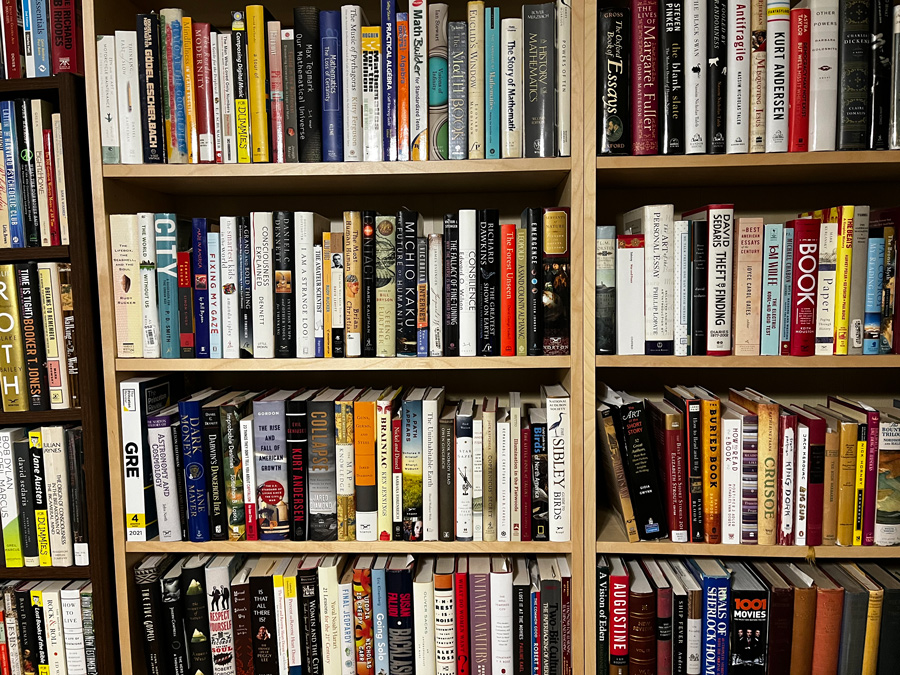

I learned several things this week while entering over fifteen hundred books into my Goodreads database. The books I added were mainly acquired since I retired in 2013. One insight that impressed me the most was I was specializing in a limited number of topics. On one hand, I was disappointed by my narrow range of interests, but on the other hand, I was annoyed at myself for being scattered in my intellectual pursuits. You can’t get good at something if you try to get good at too many things.

If I judged my reading as a leisure activity it wouldn’t matter what I read. However, if I judged my reading as an education, then I was majoring in too many subjects. But here’s the kicker to this revelation. Before I started cataloging my books I assumed I was reading for fun and randomly exploring any subject that caught my fancy. It was only as I entered all the titles into the database did I realize that I have been specializing in several areas. And my immediate impulse was to read deeper into those topics and to go out and buy more books on those subjects.

Why was I chasing so many subjects when I’ve always wanted to be a master of one? Why would I want to do that? Yet, focusing on one would mean ignoring many things I want to know more about. That thought has started me to do a lot of naval gazing this week.

My original goal was to put all my books into my Goodreads database so I’ll know what I own to keep from buying duplicates when I’m at the used bookstore. So far I’ve found a shopping bag of duplicates which I gave to my buddy Mike. I entered all my books into Goodreads many years ago but didn’t update the database when I bought books or gave them away, so my Goodreads database was badly out of date. I had been putting this task off for years because I couldn’t figure out which books to add or delete from the system to catch up again.

My solution was to create a “shelf” called “2023 inventory” and reenter all my books linking them to that shelf. Then delete all the books in the system that wasn’t in the 2023 inventory.

After entering 1,506 books, which were all the physical books in the house, I had 3,159 total books in the database. That implied I could have given away 1,653 books, but then I realized that some of those might be Kindle or Audible books I own. Now I must go down the list of 3,159 books, and if they aren’t in the 2023 inventory, see if they are in my Kindle or Audible libraries. If they aren’t, I can delete them.

Doing all this librarian work has been rewarding in several ways. The work is revealing how my reading has shifted away from physical books to ebooks and audiobooks. This process has also revealed other insights about myself. For certain titles, and subjects I tend to buy both the audiobook and the ebook edition because that’s how I like to study them. And for some titles, I have the ebook, audiobook, and physical book. If I really like the book and subject, or if it’s fiction, and I really enjoy the story, I like getting into the book through all three formats.

I can spot my favorite authors because with some writers I’ve collected their books in all three formats. That also reflects a consolidation of interests, focus, and specialization.

When I used to go to parties I noticed that people tend to talk about things they loved most. The most interesting people were the ones who could expound deeply on a subject. Like most people, I just chatted about what little I knew about a zillion subjects.

I eventually observed that some people like to specialize and that some people even feel they are experts on their favorite subjects. It’s even fun to see two fans of the same subject argue over who knows more. I see from my data entry the subjects I’ve unintentionally tried to master. What’s funny is I seldom meet people interested in the subjects I’m interested in. Which is why I seldom talked much at parties. (This blog is my way of nattering about what I like.)

Thinking about people who know a lot about a little has led me to ask why I’d want to specialize in certain topics anyway? It’s not like I’m at a university trying to pass courses and get a major. I never go to parties anymore. I think it’s like my urge to catalog my books, which is a kind of anal pursuit, I also want to organize what I know.

There is a certain satisfaction in getting the biggest picture on the tiniest of topics. There is also satisfaction in collecting everything of a certain type. For example, I like westerns, so I collected my favorite western movies on DVDs. Then I started buying books about movie westerns. But after that, I started buying books about the history of the American West. I’ve done the same thing for classic rock and jazz music. While cataloging my books I realize I was gathering novels written in England between the wars, and books about their authors. That interest is also reflected in the TV shows I’m watching. Susan and I have recently watched all of Downton Abbey, Upstairs, Downstairs, and we’re currently going through the seven seasons of the first television version of All Creatures Great and Small.

The upshot of all these cataloging revelations is I want to focus more on my best subjects. And abandon some lesser interests to put more time into my majors. After I finish this project I could write my tombstone epitaph – “Here lies Jim Harris, this is what he liked to read:” I mean, isn’t what we focus on one of the best descriptions of our personality?

I only have nine bookcases. And they are all full. I don’t want to buy more bookcases. Nine’s my limit. I feel that’s also an analogy for my brain. It can only hold so much, so if I want to get better at one subject I have to forget about another.

If I want to buy more books I have to get rid of existing books to make room for the new ones on the shelves. This tends to distill my collection even further into specialized subjects. It also means I cull crappy books for better books.

But there is something else to consider. I’m getting older. I’m running out of time. My mental abilities are declining, which limits how much information I can process. And my physical abilities are declining, which also influences my book collecting. I can imagine a future where I can only handle six bookcases, or even three, and maybe down to just one.

I put every book I own onto a Rubbermaid rolling cart one shelf at a time to take them to my computer to enter their data. That physically wore me out. I’m thinking of getting rid of the heavy coffee table books in my collection just because in the near future I won’t be able to handle their weight. And there’s another reason I need to start shrinking my collection. If I should die I don’t want to burden my wife with having to get rid of a couple of tons of books. And if I ever need to move to a retirement apartment or assisted living I wouldn’t want to deal with all of them either.

This week of cataloging my books has reminded me of which subjects I’ve studied over the last forty years, which subjects are my favorite topics, and that I want to thin out my collection.

Currently, Goodreads says I have a total of 3,150 books but I haven’t finished entering all my Kindle and Audible books. Amazon says I have 1,608 Kindle books and 1,544 Audible titles, however, many are already in Goodreads. I’ve just got to figure out which ones aren’t. Luckily, Kindle and Audible books don’t weigh much, or take up much space.

I’ve always wanted to make a list of everything I own because I assume it would tell me a lot about myself. This Goodreads list is a good start toward that.

JWH