by James Wallace Harris, Friday, December 4, 2020

I have never been to San Francisco but over my lifetime I’ve read many books about social movements that city produced. They include the Beats (1950s), Rock (1960s), Gay Liberation (1970s), and Silicon Valley (1970s, 1980s). Anna Wiener’s 2020 book Uncanny Valley is about San Francisco of the 2010s, although I’d say mainly about from 2013 to 2016 when Trump is elected president with a bit of updating to 2018. Anna Wiener was on the peripheral of several interesting news events of the decade, so even though this is a personal memoir, she had a stadium seat to some significant social upheavals that affected more than just San Francisco. This is probably why The New York Times chose Uncanny Valley as one of the “Ten Best Books of 2020.” It was also on these best of the year lists from Esquire, NPR, and Parade. Bookmarks which tracks links to reviews found mostly rave reviews.

Describing what Uncanny Valley is about will be hard. Wiener, graduated from college in 2009 and went to work for publishers in New York, and then at age 25 moved to San Francisco to work at a succession of three internet startups, the most famous of which was GitHub. I’m a computer guy who loves books about the history of computers and computing. I was hoping Uncanny Valley would be another The Soul of a New Machine by Tracy Kidder. It wasn’t. Anna Wiener wasn’t a programmer or computer engineer, and her memoir is not really about computers even though it focuses on people who passionately are.

Wiener’s role in her story was much like Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby, as a commentator on the main characters, or like Tom Wolfe in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Wiener was an observer of a social revolution, not a revolutionary herself. Wiener gets to know the revolutionaries, their causes, their ambitions, their faults, their crimes, their successes and anguishes. Wiener tries to understand the philosophical implications of this revolution but it’s too complex.

The young millenials who become millionaires and billionaires creating tech startups in San Francisco have a lot of overlap with the counterculture revolutionaries of the 1960s. They imagine reshaping society with similar utopian ideals, justifying their hubris with similar sounding pop philosophies, they indulge in drugs, alternative lifestyles, leftover New Age faiths, wild conspiracy theories, and silly science fictional schemes that have echos in previous cultural revolutions. They even contemplate engineering cities from scratch like hippies use to dream about communes. But this time around they are capitalists and they all want to get mega rich.

Silicon Valley and San Francisco are not everyday America, but they impact it in a way we can’t escape. Most of us live at least part-time on the net, joining the hivemind subculture Silicon Valley created. Anna Wiener lived in the eye of the hurricane collecting data readings she hoped would reveal meaning. I’m not sure anyone can make sense of that era. She felt bad and blamed herself for failing, but that’s silly. What she has done is taken excellent notes about her experiences and impressions.

Uncanny Valley could be a textbook supplement for a graduate course on current issues in business and business ethics. It could also be a meditation guide for young people who contemplate their own participation in society. Like the Beats in the 1950s, and the Hippies in the 1960s, and the New Agers in the 1970s, the millenials are struggling to make sense of life and find a righteous path for living in a corrupt world of commerce. Like every generation, they’re looking for meaning in a meaningless reality. In some ways, Uncanny Valley reminds me of The Making of a Counter Culture by Theodore Roszaks – but who remembers that 1969 book?

Throughout this memoir I kept feeling the people Wiener described were going through many of the same psychological struggles I did in the 1960s and 1970s. It’s a chronicle of typical youth angst. Of course, that left me wondering if we can ever solve the problems we all rail against early in life, but which we eventually forget when we co-opt ordinariness.

The only thing unique about Wiener’s generation is how some of them got so damn rich. Part of Uncanny Valley deals with the problems of chasing those billions, and soul changing of catching mountains of money, or the agony of failing to become wealthy.

Even though this is a short book, there’s a great deal to it, really too much to digest, including many ethical issues created by the business models of these new tech industries. Often Wiener would be working on software that got into the news for its evil side effects. Or that same software would empower legions of formerly powerless people to do evil. She often worried about the degree of guilt that belong to her.

Ultimately, Uncanny Valley becomes a must read book because Anna Wiener just happened to be in the right place at the right time to glimpse at generation changing events. Nearly everything she writes about has been well documented in news stories over the last decade. If you’ve been paying attention, a lot of it will be familiar. Weiner got closer than most reporters. However, she obscures the names of everything. I found this very annoying, but finally accepted it as a quirky writing affectation. In one review I read, it was suggested she Wiener had to sign so many non-disclosure agreements she’s become shy of using real names for anything. Of course, Wiener might have thought it funny to make us guess.

I don’t know how often I convince blog readers here to read what I review. Uncanny Valley could bore the crap out of most of my friends, or it could dazzle them. If you like nonfiction and memoirs, and interested in issues dealing with current events, profiles of younger generations, sexism, privilege, technological change, politics, economic equality, ecology, homelessness, gentrification, capitalism, and contemporary ethical issues, then this book might be for you. If reality overwhelms you, you should avoid it like the Covid.

Additional Reading:

- Anna Wiener’s columns at The New Yorker

- A Tech Insider Stylishly Chronicles Her Industry’s ‘Uncanny Valley’ – New York Times

- Inside Tech’s Fever Dream – The Atlantic

- The Millennial Meaninglessness of Writing About Tech – Wired

- Uncanny Valley by Anna Wiener review – bullies, greed and sexism in Silicon Valley – The Guardian

- Uncanny Valley: A Memoir by Anna Wiener review – beggars and tech billionaires – The Guardian

- The Loop in the Kingdom of Vectors – Slate

JWH

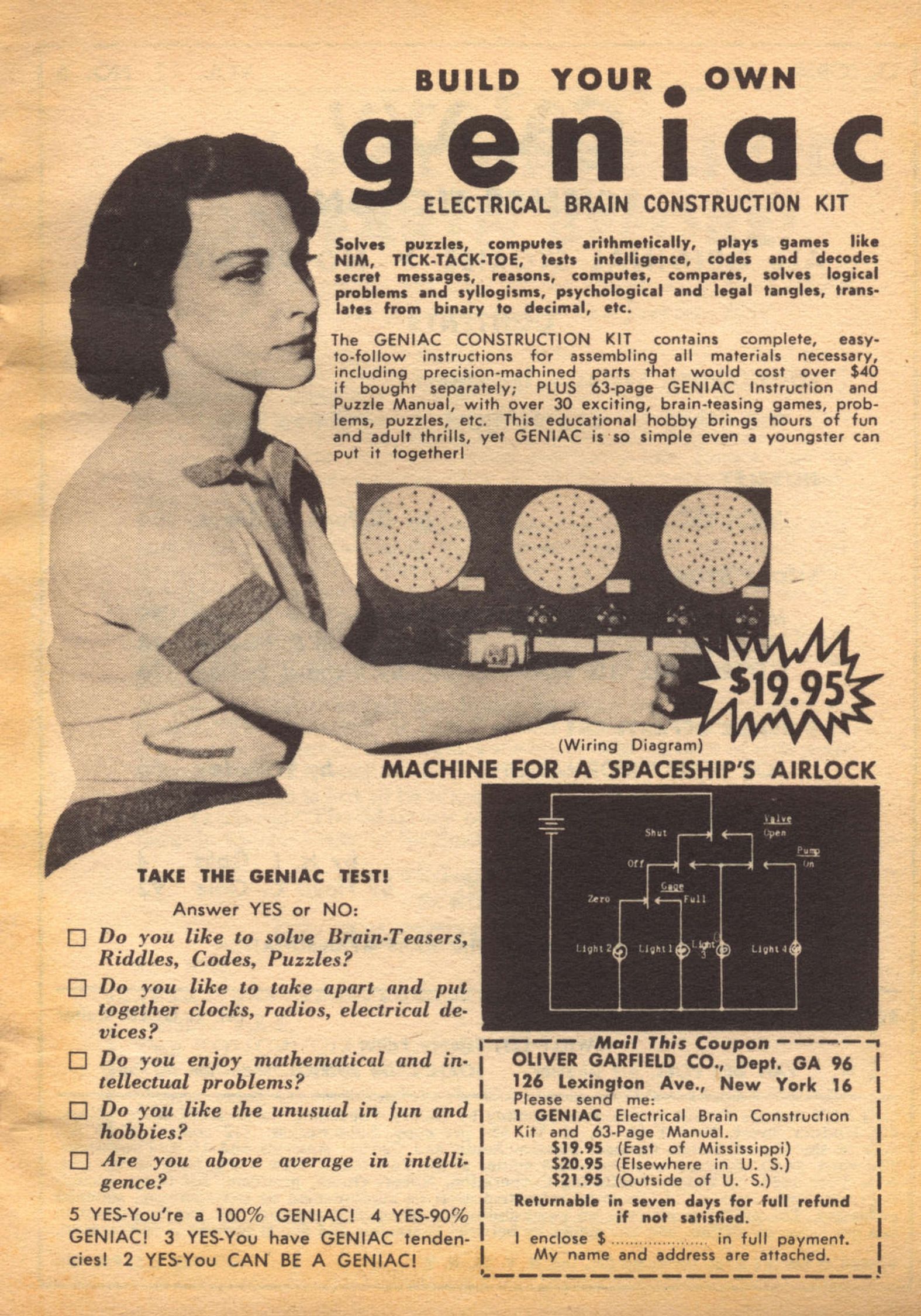

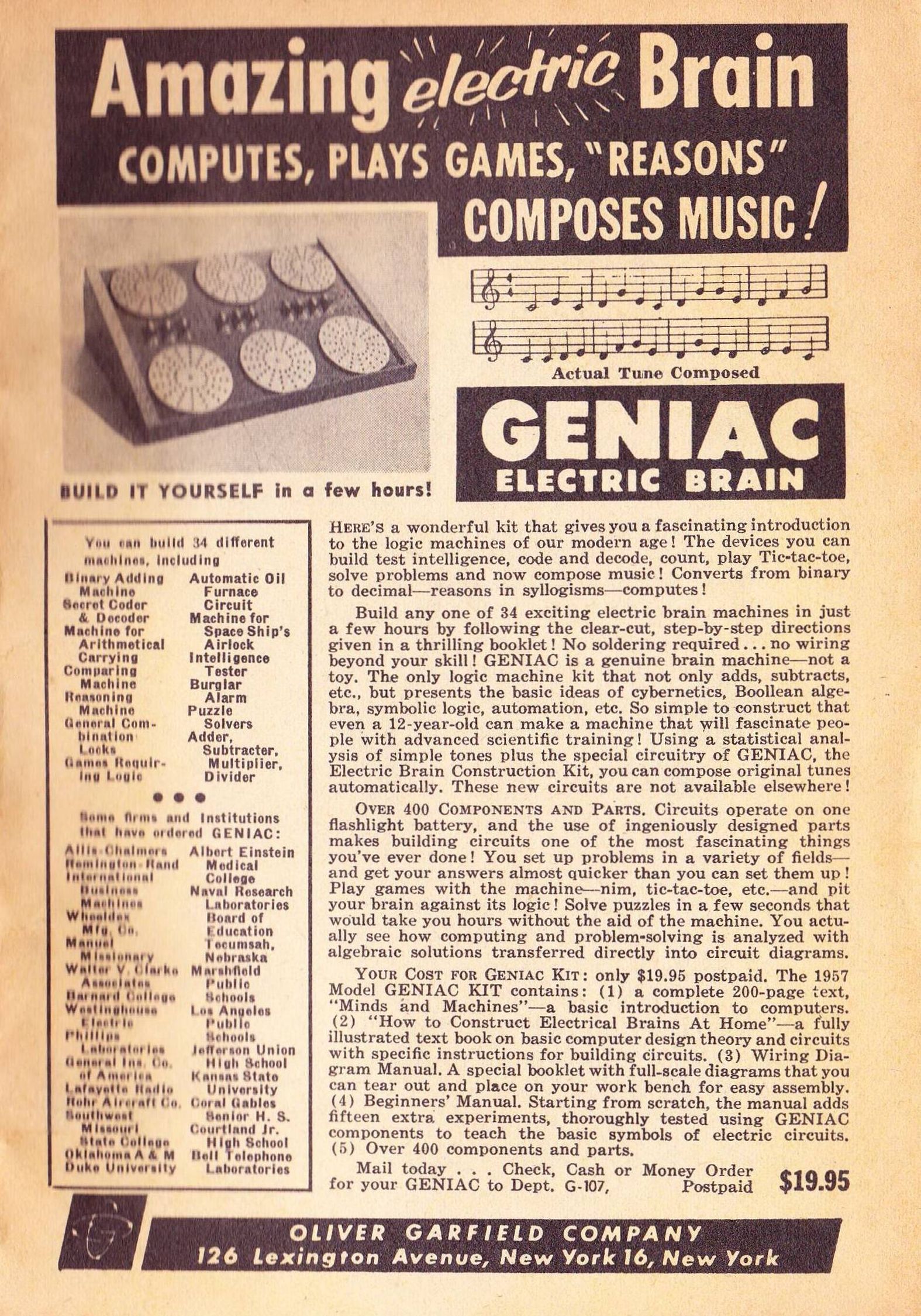

The main designer of Geniac appears to be

The main designer of Geniac appears to be