by James Wallace Harris, Monday, September 16, 2019

This morning I was flipping through some old issues of Galaxy Science Fiction I had bought on eBay and ran across this ad in the October 1956 issue:

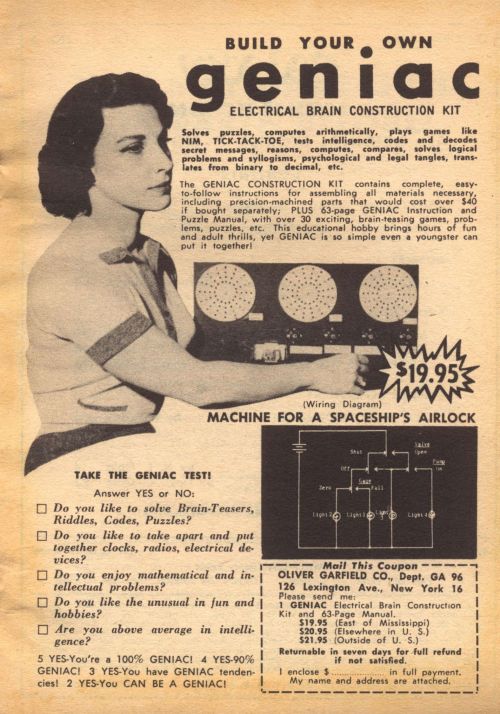

At first, I flipped right by it. Then in the next issue I picked up, the December 1956 issue, I found this ad:

This one promised a whole lot more. Could this be for real? Computes, plays games, composes music? I don’t ever remember reading about home computers existing this early. I thought computer kits were something from the 1970s. This December ad promised a new improved 1957 model, and for only $19.95. In 1956, $19.95 was some serious money for a kid. It would probably be hundreds of dollars in today’s money. And was this a genuine computer, or was it some kind of trick, like those X-Ray glasses advertised in the back of comic books?

First stop: Wikipedia.

Geniac was an educational toy billed as a "computer" designed and marketed by Edmund Berkeley, with Oliver Garfield from 1955 to 1958, but with Garfield continuing without Berkeley through the 1960s. The name stood for "Genius Almost-automatic Computer" but suggests a portmanteau of genius and ENIAC (the first fully electronic general-purpose computer). Operation Basically a rotary switch construction set, the Geniac contained six perforated masonite disks, into the back of which brass jumpers could be inserted. The jumpers made electrical connections between slotted brass bolt heads sitting out from the similarly perforated masonite back panel. To the bolts were attached wires behind the panel. The circuit comprised a battery, such wires from it to, and between, switch positions, wires from the switches to indicator flashlight bulbs set along the panel's middle, and return wires to the battery to complete the circuit. With this basic setup, Geniac could use combinational logic only, its outputs depending entirely on inputs manually set. It had no active elements at all – no relays, tubes, or transistors – to allow a machine state to automatically influence subsequent states. Thus, Geniac didn't have memory and couldn't solve problems using sequential logic. All sequencing was performed manually by the operator, sometimes following fairly complicated printed directions (turn this wheel in this direction if this light lights, etc.) The main instruction book, as well as a supplementary book of wiring diagrams, gave jumper positions and wiring diagrams for building a number of "machines," which could realize fairly complicated Boolean equations. A copy of Claude Shannon's groundbreaking thesis in the subject, A Symbolic Analysis of Relay and Switching Circuits, was also included.

Okay, so it was real! But in 1956? In the mid-fifties, commercial computers were just beginning to be rolled out to businesses. In 1957 American audiences got to see a humorous look at computers in the film Desk Set with Spencer Tracy and Katherine Hepburn. Rumors of computers produced a fear that the librarians would lose their jobs, but ultimately humans prevailed. I expect most Americans in 1957 had never seen a computer and only knew about them from funny cartoons in magazines and newspapers. Geniac came out before Sputnik which ignited a fear that American youths weren’t being educated in science. Was there a desire by kids that early in the 1950s to know about computers?

Here is a History of Computer timeline that shows the Geniac for 1955. And here’s an article about the history of computers that played NIM games, which includes the Geniac.

The main designer of Geniac appears to be Edmund Berkeley. He wrote an early book about computers in 1949, Giant Brains, or Machines That Think. Berkeley was also written about in Edmund Berkeley and the Social Responsibility of Computer Professionals by Bernedette Long. If you follow that link she writes about his influence with Geniac. I’m awful tempted to buy the Kindle edition. He also designed what some people call the first personal computer, Simon. Simon appeared as 13 how-to articles that began running in Radio-Electronics magazine in October 1950. (All 13 parts can be read online here.) It would have cost around $600 to build and had very limited features with only 2-bits of memory. Berkeley wrote the article “Simple Simon” for the November 1950 issues of Scientific American.

The main designer of Geniac appears to be Edmund Berkeley. He wrote an early book about computers in 1949, Giant Brains, or Machines That Think. Berkeley was also written about in Edmund Berkeley and the Social Responsibility of Computer Professionals by Bernedette Long. If you follow that link she writes about his influence with Geniac. I’m awful tempted to buy the Kindle edition. He also designed what some people call the first personal computer, Simon. Simon appeared as 13 how-to articles that began running in Radio-Electronics magazine in October 1950. (All 13 parts can be read online here.) It would have cost around $600 to build and had very limited features with only 2-bits of memory. Berkeley wrote the article “Simple Simon” for the November 1950 issues of Scientific American.

Electronics was a big tech hobby back then and had been since the early days of the radio in the 1910s. Looking at the Geniac ad carefully though showed it wasn’t an electronics kit, but merely electrical. It might contain 400 parts, but they were wires, light bulbs, batteries, nuts, and little contacts. It seems designed to set up simple logic programs. How much could a kid do with one? YouTube to the rescue:

And this film, which features a later model from the 1960s called a Brainiac:

This brings up even more questions. Did kids really play with them? Where they inspired to study computers and become computer programmers and engineers? Were there any famous computer pioneers that started with a Geniac or Brainiac? Could Steve Wozniak or Bill Gates have played with one? Of course, those two might have been too young for this era.

The kit seemed aimed at kids, but it would have required a great deal of work and patience to produce any results. Actually putting one together and doing any of the example projects would have been very educational.

David Vanderschel describes his Geniac computer from 1956. He says an IBM 1620 was the first real computer he encountered in 1962. That was the first computer I programmed on in 1971 at computer school using FORTRAN.

Hackaday had a post last month about the Geniac claiming that Mike Gardi credits his professional success in software development to educational logic games like the Geniac. Gardi created a replica of a Geniac and has links to the original documentation. This 1955 manual had instructions for a couple dozen projects. Gardi said:

Technically GENIAC was a collection of configurable N-pole by N-throw rotary switches, which could be set up to cascaded and thus perform logical functions. As a result GENIAC could use combinational logic only, its outputs depending entirely on inputs manually set. However, projects outlined in the manual, which started with basic logic circuits, ultimately progressed to such things as a NIM machine and TIC-TAC-TOE machine.

I did find a Geniac on eBay that has a $99.99 buy it now price. There’s a Brainiac for sale for $349! That’s more than I’d want to spend. The Brainiac is in great shape though. It’s probably the one from the film above.

The more I Googled, the more intrigued I became about the impact of the Geniac computer. Is this how historians get sucked into writing books? I checked a couple books on the history of personal computers I own, but neither mention Geniac or Edmund Berkeley. If you search Google for the first personal computer you usually get the MITS Altair 8800. Maybe that’s not true. Maybe I could write a whole history book about home computers before 1975.

Additional Reading:

- Pop Quiz: What was the first personal computer?

- A Machine to Compose Music

- Superman: How a Trademark Dispute Led to a Major Brainiac Retcon!

- History of the Personal Computer

- A Shortcut Through Time

- Timeline of Computer Science

Update:

I went to my public library and looked through the books about the history of computing. I found no mentions of Geniac or Edmund Berkeley. I then checked The Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature for the years 1950-1960. I found no references to Geniac and only a handful of articles by Berkeley. His articles did sound interesting:

- “Robots for Fun” Life, 173-74+, March 19, 1956

- “Relations Between Symbolic Logic and Large-Scale Calculating Machines” Science, 395-399, October 6, 1950

- “Simple Simon” Scientific American, 40-43, November 1950

- “Tomorrow’s Thinking Machines” Science Digest, 52-57, January 1950

- “2150 A.D. Preview of the Robotic Age” New York Times, 19, November 19, 1950

- “Robot Psychoanalyst” Newsweek, 58, December 12, 1949

- “Algebra and States and Events” Science Monthly, 332-342, April 1954

- “We Are Safer Than We Think” New York Times, 11, July 29, 1951

An amusing thing happened at the library. I kept asking the librarians where the Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature was located. They didn’t know. Finally, they asked a very old librarian and she found it for me. She then came back with the younger librarians, they wanted to see it too. I had told them when I was young every kid was taught to begin their library research with that classic index.

JWH