by James Wallace Harris, 12/30/21

Reading is my sixth sense, how I explore the larger reality I can’t observe with my classic five senses. Every year I can only read so many books, making it important to wisely select the novels, nonfiction books, short stories, and articles I do read. Reading changes me. I shape myself by what I read. Each year I work to become more conscious by what I select to read. However, this self-improvement effort is very much like my efforts to eat healthily and avoid junk food. I’m never a saint.

At seventy, my mind is becoming like an old suit with moth holes. Words and thoughts leak out of my consciousness through little missing places eaten away by the moths of time. Remembering is something that’s become very important to me, as much as sex was on my adolescent mind.

The Reading List by Sara Nisha Adams is the 52nd and last book I read in 2021. It’s an accomplishment to read so many books in one year. And 52 is a good number. It means I averaged one book a week, and that’s a nice reading pace.

I’ve always wanted to be one of those superbookworms who could read 100 or 200 books a year, but my mind and memory can’t handle that much new content. I like to think one book a week is what my mind can handle, but I’m probably fooling myself.

52 is probably too many but I’d hate to read less. I feel I did a pretty good job of picking worthwhile reads, ones I still remember reading at the end of the year, but I have to admit, some of them were not necessarily the best books I could have picked. I will try harder next year. The problem is the conflict between reading books that expand my awareness, and books that soothe my soul.

One way to remember the books I read in 2021 is to remember my favorites, the ones I’d recommend. Links are to essays I wrote during the year.

New Fiction

- Crossroads by Jonathan Franzen

- The Reading List by Sara Nisha Adams

- Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro

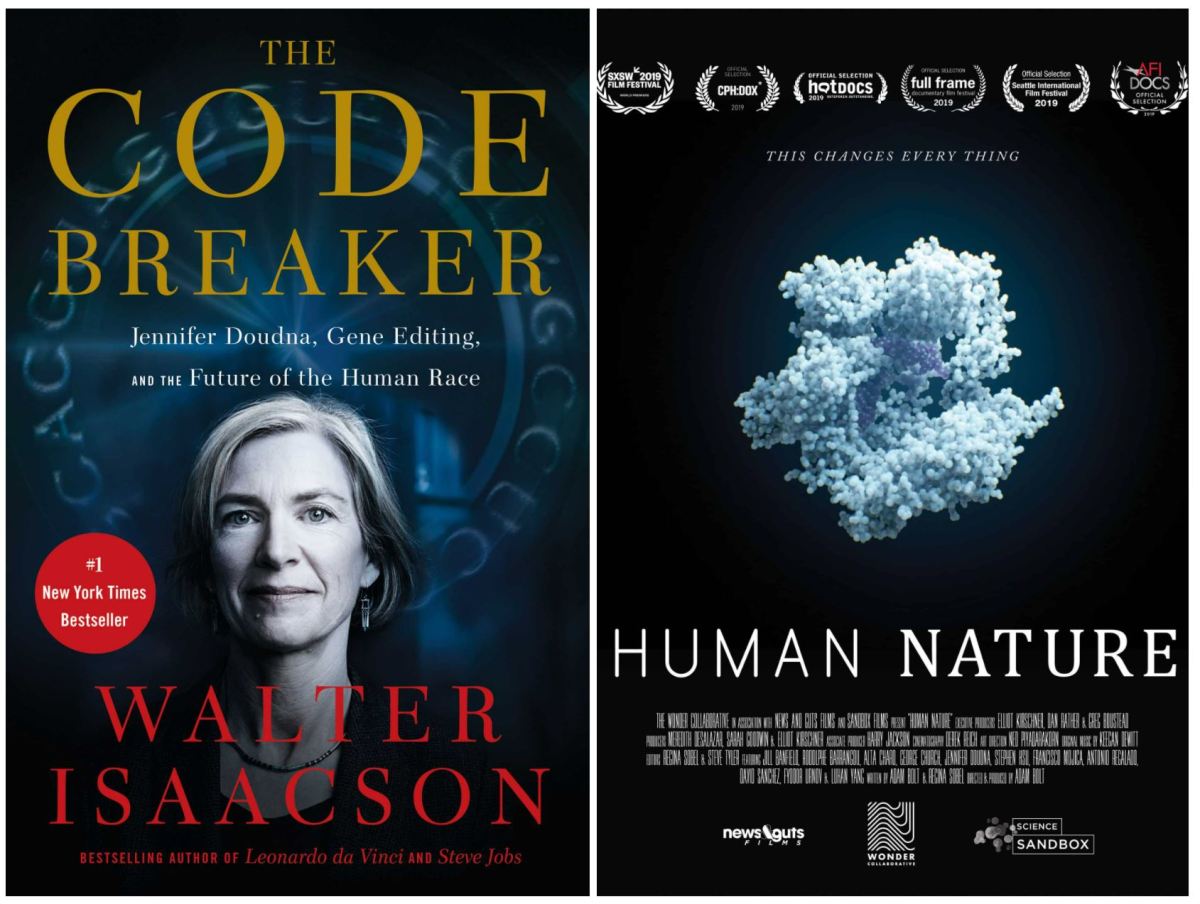

New Nonfiction

- The Code Breaker – Walter Isaacson

- Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause – Ty Seidule

- Last Best Hope: America in Crisis and Renewal – George Packer

- The Premonition: A Pandemic Story – Michael Lewis

- Under a White Sky – Elizabeth Kolbert

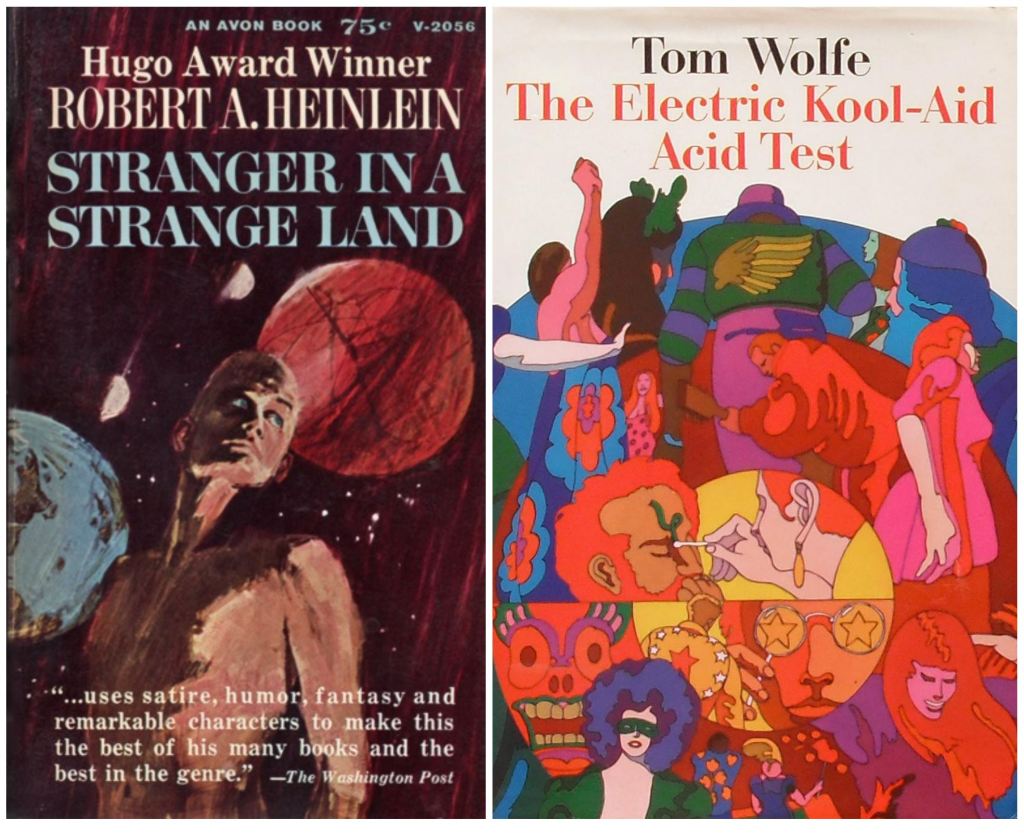

Old Fiction

- The Pursuit of Love/Love in a Cold Climate/Don’t Tell Alfred (trilogy) – Nancy Mitford

- Of Men and Monsters – Willian Tenn

- To Say Nothing of the Dog – Connie Willis

- Leaving Cheyenne – Larry McMurtry

- The War of the Worlds – H. G. Wells

- The Man Who Fell to Earth – Walter Tevis

Old Nonfiction

- The Invention of Nature – Andrea Wulf

- Evil Geniuses – Kurt Andersen

- The Art of Dying Well – Katy Butler

- Hackers – Steven Levy

- The Sisters – Mary S. Lovell

- LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media by P. W. Singer

Another way to remember is to recall why I read certain books. I’m in a two-person book club with my friend Linda, I’m also a member of an online nonfiction book club, I’m in a Facebook group that reads science fiction anthologies, I have a personal reading goal to read all 25 volumes of The Great SF Stories edited by Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg, I like to read science fiction novels, I love to read popular science books, and I enjoy reading some contemporary and classic fiction.

Two-Person Book Club With Linda

- Evil Geniuses: The Unmaking of America – Kurt Andersen

- Horseman, Pass By – Larry McMurtry

- 21 Lessons for the 21st Century – Yuval Noah Harari

- Leaving Cheyenne – Larry McMurtry

- The Art of Dying Well – Katy Butler

- Robert E. Lee and Me – Ty Seidule

- The Code Breaker – Walter Isaacson

- Elderhood – Louise Aronson

- Last Best Hope: America in Crisis and Renewal – George Packer

- Crossroads – Jonathan Franzen

- The Premonition: A Pandemic Story – Michael Lewis

Linda went on to read several more Larry McMurtry books, but I just couldn’t keep up with her.

Online Nonfiction Book Club

- Underland: A Deep Time Journey – Robert MacFarlane

- The Sisters – Mary S. Lovell

- Robert E. Lee and Me – Ty Seidule

- The Invention of Nature – Andrea Wulf

- Noise (didn’t finish) –

- Uncanny Valley (read in 2020) – Anna Weiner

- Ten Lessons for a Post-Pandemic World – Fareed Zakariia (didn’t finish)

- Fermat’s Enigma – Simon Singh (didn’t finish)

I had read The Sisters, Uncanny Valley, and The Invention of Nature on my own and nominated those books. I skipped four books this year: Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake, Forgetting by Scott A. Small, Kindred by Rebecca Waggs Sykes, A Promised Land by Barack Obama.

Nonfiction I Picked

- Hackers – Steven Levy (reread)

- Yesterday’s Tomorrows – Mike Ashley

- LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media – P. W. Singer

- A People’s History of Computing in the United States – Joy Lis Rankin

- Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M. – Sam Wasson

I love reading about the history of computers, and the history of science fiction. Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M. is about the making of Breakfast at Tiffany’s. I also love reading about pop culture history.

Facebook Group – Best Science Fiction and Fantasy Short Fiction

- Year’s Best SF 1 – ed. David Hartwell

- Orbit 1 – ed. Damon Knight

- The Very Best of the Best ed. Gardner Dozois

- The Year’s Best S-F, 5th Annual Edition – Judith Merril

- The Dark Side – ed. Damon Knight

- World’s Best Science Fiction 1968 – ed. Donald Wollheim

- The New Space Opera ed. Gardner Dozois

- The Year’s Best Science Fiction 3rd Annual – ed. Gardner Dozois

- The Big Book of Science Fiction – ed. Ann and Jeff VanderMeer (58% finished)

This group gets me to read a great deal of science fiction short stories. We discuss one short story a day, but I don’t read every day’s story. Still, probably over 200 stories. I really enjoy this group, and I’m learning a tremendous lot about the history of short science fiction. I’ve probably read over 400 short stories this year because of other SF anthologies and magazines I read on my own.

The Great SF Stories

- The Great SF Stories 16 (1954) – ed. Asimov/Greenberg

- The Great SF Stories 17 (1955) – ed. Asimov/Greenberg

- The Great SF Stories 18 (1965) – ed. Asimov/Greenberg

I’ve been working through this 25-volume series since 2018. I’ve become immensely fond of this series. It’s a shame they are out of print. I own all twenty-five in paperback, but I read them on my iPad from pdf copies found on the internet. I keep hoping the Facebook group to vote to read the entire run. We do start volume 25 on the 29th of this month. I’d love to finish off the series in 2022, but that would be reading 7 more volumes in 2022 and that probably won’t happen.

Science Fiction

- The Ministry of the Future – Kim Stanley Robinson

- The Man Who Fell to Earth – Walter Tevis

- Klara and the Sun – Kazuo Ishiguro

- Children of Ruin – Adrian Tchaikovsky

- The Clockwork Man – E. V. Odle

- Past Master – R. A. Lafferty

- Of Men and Monsters – William Tenn

- Lords of the Psychon – Daniel F. Galouye

- The Dying Earth – Jack Vance

- The War of the Worlds – H. G. Wells

- Danny Dunn and the Anti-Gravity Paint – Abrashkin & Williams

- A Gift of Time – Jerry Merritt

- The Best of Walter M. Miller, Jr. – Walter M. Miller, Jr.

- To Say Nothing of the Dog – Connie Willis

That’s a total of 26 science fiction books. Far more science fiction than I believe I should be reading. Each year I tell myself I should read less science fiction and more other kinds of books, but I can’t seem to break my life-long science fiction addiction.

General Fiction

- Horseman, Pass By – Larry McMurtry

- Leaving Cheyenne – Larry McMurtry

- The Girl on the Boat – P. G. Wodehouse

- The Pursuit of Love – Nancy Mitford

- Love in a Cold Climate – Nancy Mitford

- Don’t Tell Alfred – Nancy Mitford

- Crossroads – Jonathan Franzen

- The Corrections – Jonathan Franzen

- The Reading List – Sara Nisha Adams

I’m disappointed that I didn’t read a new 19th-century classic. Last year I read War and Peace. I did read The War of the Worlds, but I’ve read it a couple of times before. I had planned to read Madame Bovery.

2021 Books

- Klara and the Sun – Kazuo Ishiguro

- Yesterday’s Tomorrows – Mike Ashley

- Robert E. Lee and Me – Ty Seidule

- The Code Breaker – Walter Isaacson

- Last Best Hope – George Packer

- Crossroads – Jonathan Franzen

- The Premonition – Michael Lewis

- Under a White Sky – Elizabeth Kolbert

- The Reading List – Sara Nisha Adams

Each year I aim to read a certain number of books that come out during the year. Nine is pretty good for 2021, but I’m going to aim for 12 in 2022.

JWH