by James Wallace Harris, 8/24/24

On Monday, August 19th, the New York Times ran a guest editorial by James Pogue about Senator Chris Murphy of Connecticut, entitled “The Senator Warning Democrats of a Crisis Unfolding Beneath Their Noses” which I found intriguing but hard to understand. It appears to suggest that Republicans are going to put limits on neoliberalism. That’s impossible for me to believe.

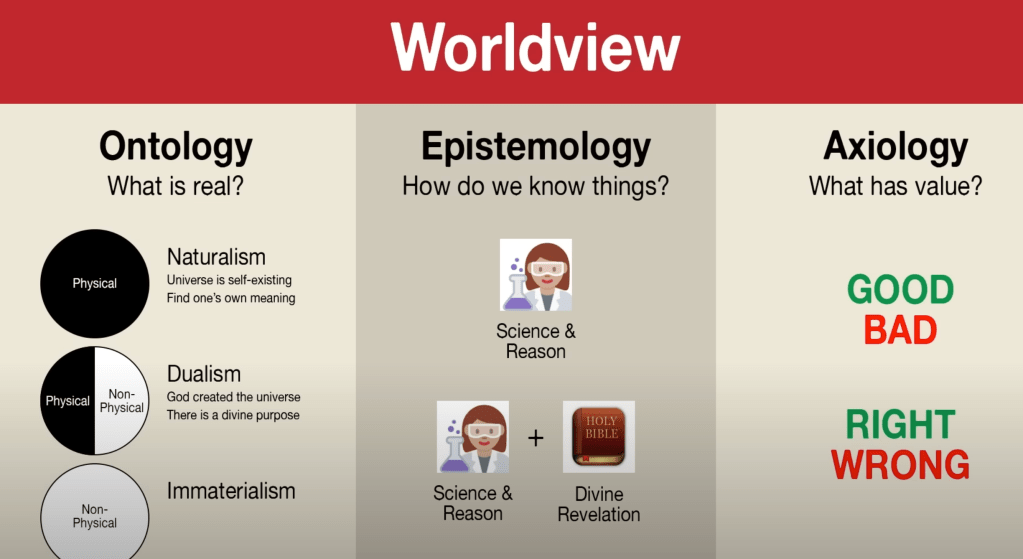

That’s a rather interesting statement, that the problems we face today aren’t logistical but metaphysical. Pogue then goes to say the subject of Murphy’s speech was “the fall of American neoliberalism.” I’ve read several articles over the last few years that mentioned the same thing. Neoliberalism is a virulent form of capitalism pushed by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. It’s an economic philosophy embraced by Republicans, but Bill Clinton went along with it when he got his chance. So did Obama. It was Trump who appeared to put on the breaks Neoliberalism when he was elected, and Biden even followed Trump in some ways. So, some pundits are now suggesting the tide has turned.

But has it? Isn’t prosperity through economic success what Republicans and Democrats both want? Pogue goes on to summarize:

Okay, I understand this. Civilization is collapsing and ultimately capitalism is a Ponzi scheme that will fall apart as the one percent squeezed all the wealth out of the ninety-nine percent. But I assumed we need to fix neoliberal capitalism, not reject it. It’s the only system that creates jobs and freedom. We just needed to make it more equitable and friendly to the environment. I assumed that’s what the Democrats want, but evidently according to this essay it’s not the solution the Republicans want.

Pogue says Murphy defines it as a metaphysical problem that masks a spiritual crisis, one that Donald Trump has tapped into. Trump recognizes this unhappiness and appeals to it. Murphy says Democrats have trouble even admitting that it exists. But where does neoliberalism come in? Trump heads the Republican party, and isn’t that party the guardian angel of neoliberalism?

How can a political party overcome a spiritual crisis and still race full steam ahead with capitalism? Pogue summarizes Murphy’s recognition of the problem that the Democrats need to address:

This makes things even more puzzling. I can understand where Democrats might want to regulate capitalism, making it more socialistic and ecological, but how can Republicans alter their religion to help the dissatisfied?

Murphy brings up Project 2025 but is that really a solution to the spiritual crisis he’s pointing at? Ever since FDR and the New Deal, Republicans have been wanting to undo it, and LBJ’s Great Society too. But wasn’t Neoliberalism a response to the Great Depression? But does Project 2025 offer a solution to Murphy’s problem? Isn’t it just consolidating power. It doesn’t claim to undo neoliberalism. Although, it hopes to rewind our sociological makeup back to the 1920s.

To me, the Republicans want to avoid taxes and regulations so they can make as much money as possible. They want private property protected and they want national security. Neoliberalism gives them all of that, so why would they want to undo it? I don’t think they do.

Lately, I’ve been reading books on the French Revolution and Napoleon. The French Revolution tried to create a democratic society based on Enlightenment ideals. The revolutionaries wanted to get rid of the aristocracy and the church. Napoleon believed democracy would just allow a class of wealthy to replace the aristocracy, and that either would need to keep the church because the church kept the poor from destroying either the aristocracy or the wealthy. Napoleon didn’t care for democracy and felt a hereditary aristocracy was a better system for maintaining order. He reinstated the church.

Aren’t the Republicans wanting to be the new aristocrats, and aren’t they embracing the faithful to protect them? Trump and the Republicans want to consolidate power. Is their promise of law and order going to solve the spiritual crisis that Murphy describes?

If the Republicans win in 2024, roll out their Project 2025 plan, and succeed at killing off the Democratic Party, they aren’t going to solve those spiritual problems Murphy points to. They will deregulate capitalism more, cut taxes for themselves, and go back to distilling American wealth from the ninety-nine percent to the one percent. They might make some Americans happier by legislating behavior, but I’m pretty sure they won’t put the breaks on neoliberalism.

Republicans will face a real revolution, like the one in 18th-century France. And we’ll discover the same problems as the French discovered. Between the fall of the Bastille and the coronation of Napoleon, they tried many kinds of governing theories based on the desires of the different factions of the population. None of them worked.

I believe the spiritual crisis Murphy points to has always been with us. There’s no form of government that makes most of the population satisfied. That the pendulum always swings between hope and the apocalypse but never reaches either. Murphy is saying that Trump and the Republicans are swinging the pendulum towards hope. That might even be true for some, but it doesn’t mean the pendulum will reach a point and make their followers happy.

I don’t think Trump is really offering an alternative to neoliberalism economics, but just appealing to isolationism, xenophobia, racism, and is anti-LGBTQ+.

Would it be cruel of me to point out that Christians have been waiting for the Rapture for over two thousand years. Republicans have been in the desert for forty years waiting to get into the promise land. They feel they are remarkably close. Religion and politicians have been promising to deliver people into the land of milk and honey for two hundred thousand years. We’ve never gotten there yet so why believe it now?

The essay goes on for a great length, but it finally gets down to talking about what the Democrats can do in response. I worry that the Democrats might promise pie-in-the-sky. I think we need to get away from believing political parties will save us.

Democrats and Republicans vilify each other, often to extreme. Each have legitimate complaints and desires.

The whole country needs to rethink what it wants, and not trust either party. I think Trump supporters should expect to be let down. I don’t think either party can solve the spiritual crisis that Murphy describes. We have a polarized political system that is stuck with always leaving half the voters unhappy.

I don’t know if we can fix our system, or even start over with a new one that works. But my gut tells me the present two-party system won’t ever succeed. I doubt a one-party system would either. I’d like to see more democracy, not less. We need to decide everything with referendums but change what a winning majority is from 50% to 66%. We need to move closer to a consensus rather than polarization. I think that might be possible with referendums, but not with political parties. Just study opinion polls. Political parties have succeeded in making minority rule work.

I want the Democrats to win in November, but I don’t expect them to solve the spiritual crisis Murphy describes. I just expect they will provide less turmoil over the next four years. Civilization will continue to head towards collapse. Theoretically, we might avoid that, but not with our present political system.

I also think whether the Democrats or Republicans win, they are just going to slightly modify neoliberal economics. The pandemic taught us that we shouldn’t depend on globalism for vital products, but corporations aren’t going to give up on global markets or moving jobs around the world to where labor is cheap. We’ll deploy some tariffs, but then we’ve always had. But the basic tenet of neoliberalism, that capitalism generates prosperity through unhindered commerce won’t end. Capitalism is destructive to the environment, and unkind to economic losers. By its very nature, capitalism generates inequality. The Americans who are suffering the spiritual crisis Murphy describes won’t be saved.

If we evolved a system based on referendums and larger winning majorities, the political parties would slowly fade away. Philosophers have always worried about democracy leading to mob rule. I’m not sure that would be true if we increased the size of the winning majority. It would force us to cooperate. It’s too easy to create minority rule with a fifty percent winning majority.

Our present situation is due to the wealthy getting what they want. Like Napoleon said, they are the new aristocrats, and they aren’t going to give up their power, privilege, and position. Any political or economic solution to help those suffering from the spiritual crisis that Murphy worries about will have to include the power of the wealthy in their equations.

Before neoliberalism was a period where the rich were taxed more heavily, and we had a larger middle class. I doubt Trump wants to use that solution. Neoliberalism wants to stop anything that gets in the way of the rich making money. I can’t believe anyone believes that any political movement will hinder that.

Murphy is right in that the Democrats don’t deal with the issue. But I don’t believe the Republicans are offering a solution either. I think they’re just lying to get elected. Trump’s isolationist policies will create some jobs, but other policies will do away with more jobs. And if he really deports millions of illegal immigrants it will make a huge dent in the economy. Even then, those policies aren’t altering neoliberialism.

I think Murphy and others have put their finger on the problem, but I don’t see anyone offering a solution that will work. Neoliberalism has made greed almost unstoppable. I say almost, because revolutions and apocalypses do happen.

To solve Murphy’s spiritual crisis, we need a lot more jobs and a lot less inequality. Unfortunately, this era also coincides with artificial intelligence, robots, and increased automation. The dream of capitalism has always been to do away with labor, and technology is getting closer and closer to doing that.

Sorry to be so pessimistic.

JWH