by James Wallace Harris, 2/9/22

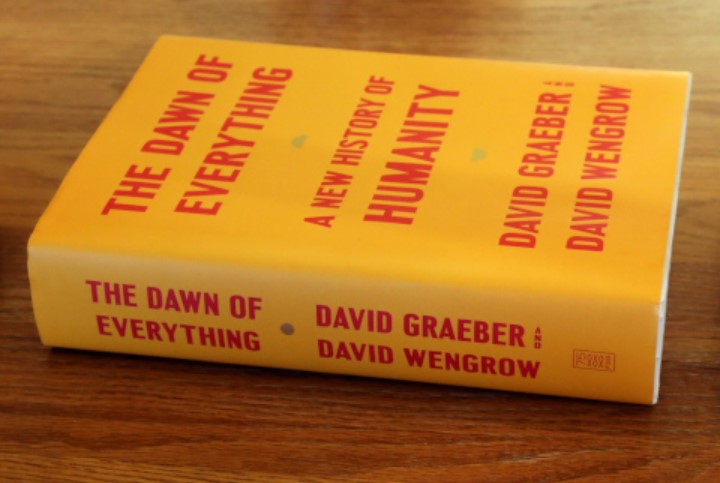

My intended fifth book to read for 2022 was Humankind, a hopeful reappraisal of humanity by Rutger Bregman. However, during the ice storm, I didn’t feel like reading serious nonfiction while the power was out. For some strange reason I was in the mood for Philip K. Dick (PKD) and I randomly picked We Can Build You. I listened to it on audio, and it was wonderfully narrated by Dan Jon Miller.

PKD wrote We Can Build You in 1962 calling it The First in Our Family while it was a working manuscript. It was rejected by his publisher, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, who had just put out The Man in the High Castle, and by several other publishers until Ted White bought it for Amazing Stories in 1969. White claimed the novel needed an ending, which White wrote with Dick’s permission. It was retitled A. Lincoln, Simulacrum and ran in the November 1969 and January 1970 issues. This is when I first read this novel. After that Donald Wollheim, who had rejected it for Ace Paperbacks, reconsidered the novel and published it for his new company DAW in 1972, but without the Ted White final chapter.

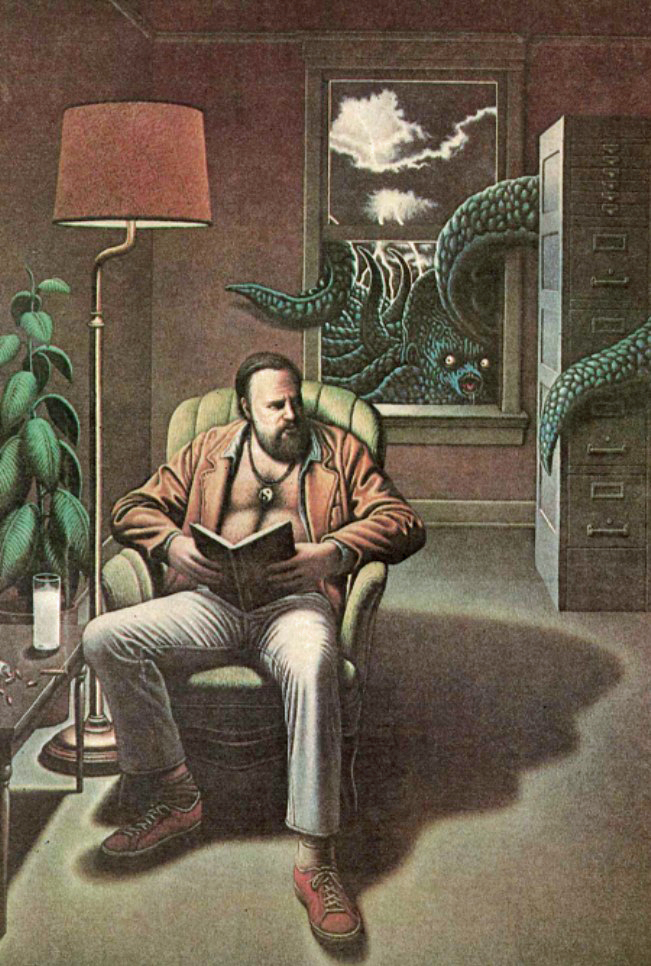

Before I digress, and I will digress all over the place, just let me say that Philip K. Dick is one of a handful of writers I obsess over. I’ve written about these writers before in my essay “The Ghosts That Haunt Me.” I’ve read many biographies about PKD, and even reviewed them as a group. And I’ve recently started reading his collected letters (I have 5 of the 6 volumes). I’m not the only one obsessed with PKD. Dick is known for writing science fiction, and he’s probably one of the most filmed of all science fiction authors. However, PKD was a troubled soul, and he often used his books and stories to explore his own psychological problems. We Can Build You is one such book.

Readers will find many stories to follow within We Can Build You. One is about Louis Rosen, a partner in a firm that sells organs and spinet pianos. Louis falls in love with his partner’s daughter, Pris Frauenzimmer, who is schizophrenic, and only 18. Louis is 33. Over the course of the novel, Louis also becomes schizophrenic. In 1962, PKD was around 33. At the time PKD wrote this novel he was married to his third wife, Anne. There is evidence that We Can Build You is somewhat biographical to PKD’s life in 1962 and is a reaction to a troubled marriage with Anne and his own psychological problems. Was there another woman? Or is Pris modeled on Anne?

Anne was an atypical PDK wife (he had five in all). Anne was a year older than Phil, and she was blonde. Dick had a neurotic obsession with dark-haired young women, and Pris Frauenzimmer, the love interest in We Can Build You is eighteen and dark-haired. Makes you wonder.

I’m giving all this information as a kind of warning. We Can Build You can be read without knowing anything about Philip K. Dick’s life. For some, especially readers who enjoy outre science fiction but don’t know PKD’s work, it will be a reasonably entertaining story, although one that will strike them as quite odd even for the outre. For fans of PKD who only read his fiction, it will even be one of the better novels, but far from his best. But, if you happen to be a Dickhead, this book offers all kinds of delicious mysteries about the bizarre and tragic life of Philip K. Dick.

Some Dickheads consider We Can Build You as a trial run for Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? It certainly focuses on two of PKD’s favorite themes: What is human? and What is Real? It’s also about insanity, a theme that runs throughout many of his stories. But it’s mainly about Dick’s obsession with young dark-haired girls, one that’s gotten its own nonfiction book. Dick was born with a twin sister who didn’t live long, and he claimed that affected him for the rest of his life.

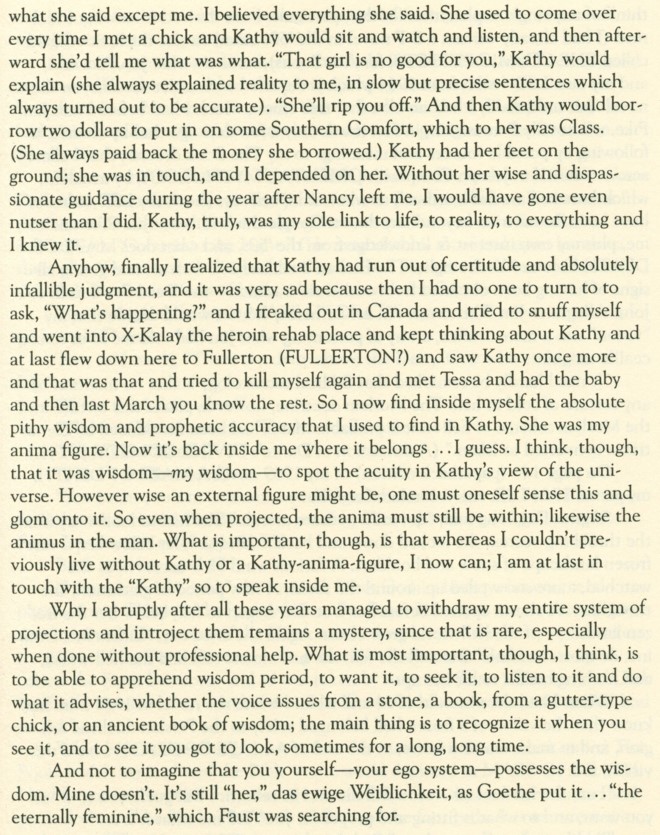

The first edition of We Can Build You in 1972 has a dedication that reads: “For Kathy Demuelle, my best friend, Mea voluptas, meae deliciae, mea vita, mea amoenitas …” Google translated that Latin for me as: “my pleasure, my darling, my life, my attractions.” This was written at the end of his marriage to his fourth wife Nancy and before he married Tessa, his fifth and final wife. These wives were barely legal for a man in his forties to marry. Dick’s published collected letters do contain letters to Kathy, and she is described in a letter to another young woman in this 1974 letter:

Kathy sounds just like Pris. But I don’t think Pris is based on Kathy. I don’t know when he met her. I need the first volume of the collected letters which I don’t have, and they are now sky high to buy used. The above letter does give us many clues as why PKD wrote We Can Build You.

However, after We Can Build You was published, Kathy evidently ghosted Phil, and he wrote Donald Wollheim asking for the dedication to be changed to Robert and Ginny Heinlein, which it is in later editions. Heinlein had out of the blue sent PKD money for medical expenses, and PKD was very moved. The early 1970s were a particularly bad time for Dick, who had suicide attempts, an escape to Canada, and had spent time in rehabs. PKD was agoraphobic but hated living alone, and often invited anyone who would, to live with him. And sometimes these were not very nice people, and sometimes they were very young dark-haired girls.

Knowing all of this should help us understand the protagonist of We Can Build You, Louis Rosen. But it’s also important to understand the major theme of mental illness and psychiatry in We Can Build You comes from a 1962 PKD, and not the 1972 PKD. Knowing the difference helps us to realize that the novel is about PKD then, but it prophesied the PKD to come.

Here’s the thing. Most readers think stories by Philip K. Dick are science fiction, but if you’re a Dickhead you realize they’re about PKD. Phil started out writing science fiction, but after he married Anne he wrote almost a dozen mainstream novels he couldn’t sell. Dick wanted to become an important writer and to support a wife that wanted that kind of success. At the beginning of the 1960s, PKD understood that wasn’t going to happen and returned his focus to writing science fiction. That’s when he published his masterpiece The Man in the High Castle in 1962. It was then PKD got the idea to blend mainstream fiction and science fiction and wrote We Can Build You.

The science-fictional elements of We Can Build You deal with building androids. The two main ones are Abraham Lincoln and his secretary of war, Edwin M. Stanton. Each android is programmed with all the biographical knowledge we have for each man. They look completely human and act like they have been reincarnated. Although they become fascinating characters integral to the story, they aren’t the important part of the story.

The novel is really a bizarre love story. Louis loves Pris, but she doesn’t love him. She is cold, cruel, and indifferent. Pris is ambitious and convives to get Sam Burrows a tech billionaire that reminded me of Elon Musk. Pris doesn’t love anyone but knows Burrows can get her what she wants. This drives Louis insane and he goes to extreme measures to take Pris from Burrows. The last third of the book is Louis undergoing therapy after having a psychotic breakdown. PKD was not the kind of man women would want, and it’s surprising he found five wives. I believe this novel conveys PKD’s frustration with his search for a woman that could make him sane and whole.

The published novel has a mainstream novel ending. Ted White wrote a science fictional ending for the magazine serialization. You can read it here, starting with the heading “nineteen.” I actually like White’s ending, but not as an ending for We Can Build You. I like it because it encapsulates how many science fiction fans think of PKD’s stories. I think they are wrong. Of course, I think I’m right in seeing PKD differently, but then I could be wrong. Reading PKD always makes you doubt everything.

Ted White’s final chapter is written knowing all of Dick’s novels from the 1960s, and White completely misses the mainstream aspects of the We Can Build You and writes a bogus PKD ending. It’s an ending that science fiction fans expect, one that falsely assumes what they think PKD is saying in the book. The ending is as different as the theatrical release of Blade Runner and Riddley’s Scott’s ending in the director’s cut. I hate Scott’s interpretation, and it’s funny that Ted White wants to use the same twist. It only goes to show you how wrong both were about Philip K. Dick.

The funny thing is I remembered White’s ending from reading it in 1970, so all the while I was listening to We Can Build You I was expecting that ending. However, I never once found any support for it.

In an April 18, 1974 letter to Claudia K. Bush, PKD tells her his favorite of his own novels are:

- Martian Time Slip

- We Can Build You

- Flow My Tears

- Doctor Bloodmoney

- The Man in the High Castle

- The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch

- The Simulcra

- The Penultimate Truth

I don’t know if he intended that list to be in order, but We Can Build You came second to mind. He even mentions in the same letter that he wasn’t sure he liked Ubik. Nor does he mention any of his unpublished mainstream novels.

Additional Reading and References

Within We Can Build You Pris works on bathroom mosaic. It turns out Anne, Dick’s third wife, created such a mosaic, while he was writing the novel.

JWH