by James Wallace Harris, 11/28/24

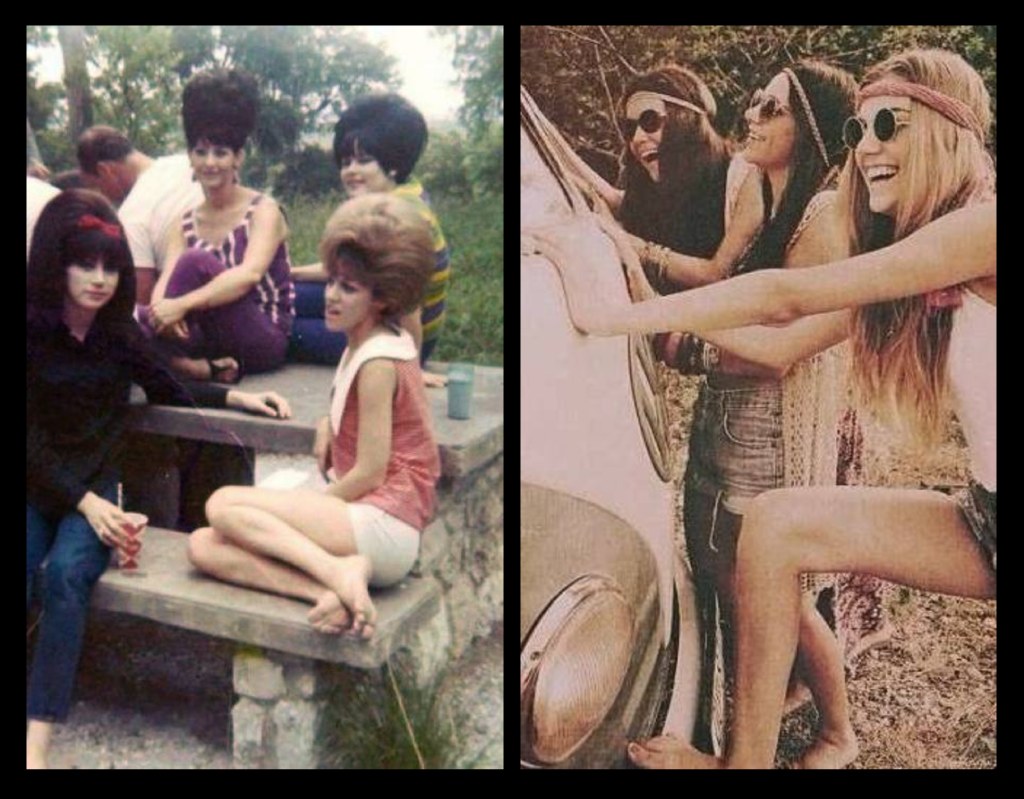

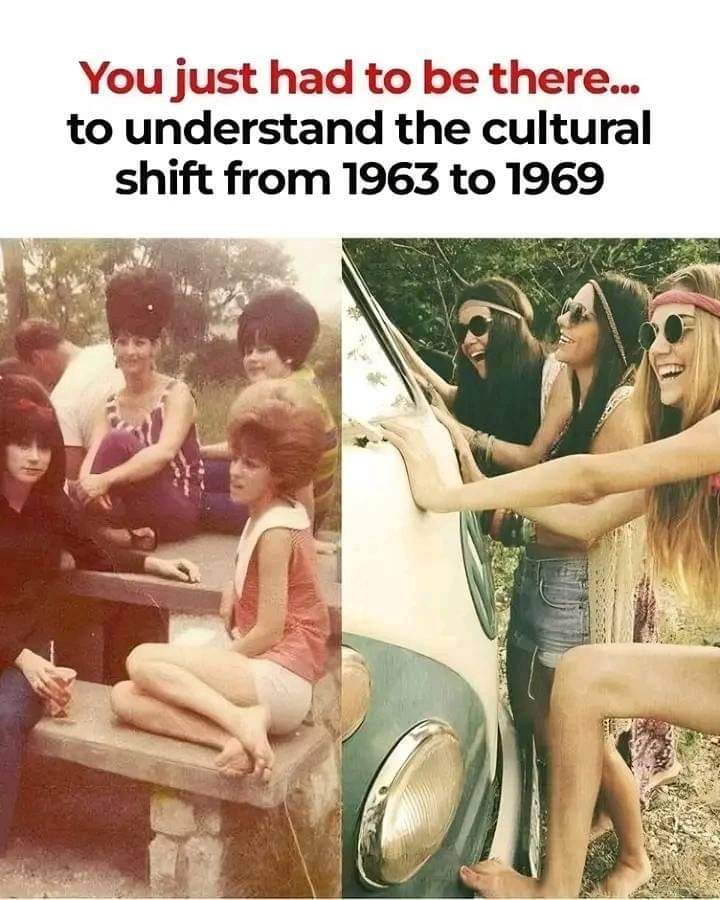

Seeing the above photos as a meme on Facebook made me think about how much people, society, and pop culture changed in the 1960s.

If a picture is worth 1,000 words, then are two pictures only worth 2,000 words? I don’t think so, I think it’s 1,000 words times 1,000 words, or 1,000,000 words. I could easily write that many from all the ideas my mind has generated since I began meditating on those photos.

Here’s the original meme from Facebook:

I was eight on 1/1/60 and eighteen on 12/31/69. I have always thought the longest years of my life were from 1963 to 1969 because so much happened to me and the world I lived in during that time. For folks who didn’t grow up in the sixties, it was much more than what you can learn from watching Grease or American Graffiti and contrasting it with Hair or Woodstock.

When I first saw the meme above I instantly thought about how rock and roll music of the 1950s ended up becoming the rock music of Woodstock. I’ve tried several times just to write an essay about that, but after typing over 5,000 words, I realize I’ve barely hinted at what I could say. That’s too long for a blog post.

I recommend that you find two photos that bracket your adolescent years or the decade you identify with the most and meditate on them. Start with remembering every place you lived and what you did each year. Remember your family and friends, your pets, your homes, your schools and workplaces, the clothes you wore, all the activities you pursued, everything you wanted to buy. Then write the shortest essay that makes it all coherent. You will then feel the mental anguish I am feeling right now.

Then branch out in your meditations. The easy and fun things to contemplate are the changes in pop culture — how music, movies, books, TV shows, games, and technology evolved over ten years. But then move on to the political and social changes. That’s when things get heavy. Can you connect your firsthand experiences with all those external events? Have you ever compared the life you lived to what you saw on the TV news every night?

Every one of us has the life experience to write a Proust-size novel and has lived through enough social change to write a series of history books about the formative decade of our lives. If you don’t think so, meditate more on the two photos you have selected.

I turned seventy-three on Monday, and getting old has made me more susceptible to memes about the past. My memories are fading away so I desperately want to cling to them. Emotions gnaw at me to make sense of everything I’ve experienced. The urge is to put it all down in words, but I don’t have what it takes to do the job and do it precisely.

There is an undefinable mental barrier that keeps me from organizing my thoughts into coherent histories. And I’m not talking about writing something worthy of publication for others to read, but just producing a narrative that makes sense of things for myself about myself and what I’ve learned. The older I get, the more I want to understand.

This essay started out about when rock and roll music became rock music. After several drafts and much contemplation, I narrowed it down to the summer of 1965 when I first heard Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” on the radio. As I kept trying to document my theory, I realized I could write a whole book on it.

Then as I was researching the subject, I found that Andrew Grant Jackson had already published the book I wish I had written, 1965: The Most Revolutionary Year in Music. His book is what I wanted to write in this essay when I first saw the meme above.

The Kindle edition is currently $2.99, and it’s a perfect example of what I’m talking about when I suggest we should chronicle our lives. Even if you don’t buy the book, read the sample at Amazon. I feel the format of organizing the narrative around a month-by-month description of what was happening is a great template to use for writing about memories.

JWH