by James Wallace Harris, Sunday, November 3, 2019

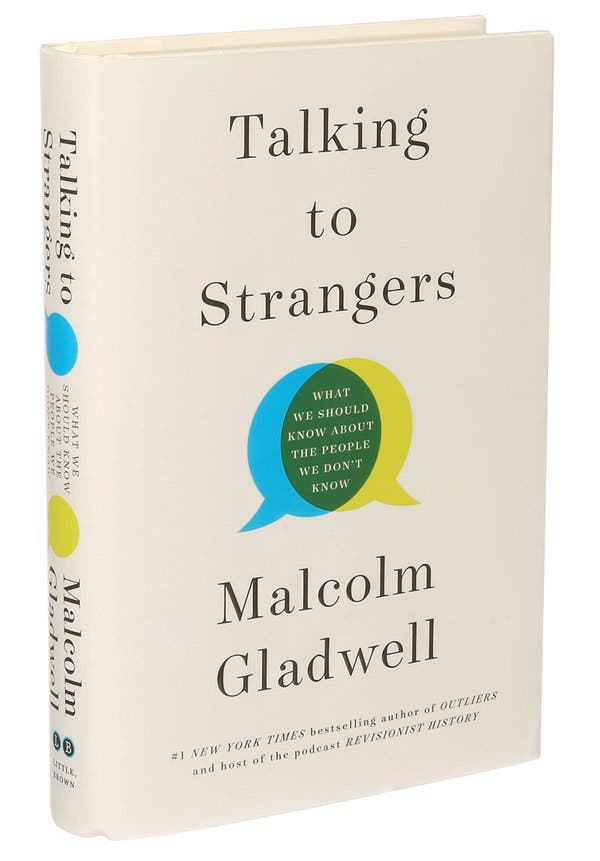

Talking to Strangers: What We Should Know About The People We Don’t Know is Malcolm Gladwell’s sixth book. I’m a big fan ever since his first book, The Tipping Point. Gladwell is an explainer, but he’s not straight forward in how he explains things. He enlightens by having the reader go step-by-step through the data he’s gathered to reach the same conclusion he has carefully discovered himself. He doesn’t just try to tell us the answer. Gladwell sees the world multidimensionally, so simple explanations won’t do.

In Talking to Strangers Gladwell wants us to understand what happened to Sandra Bland. Bland was pulled over for not using her turn signal when changing lanes, ended up being arrested, and committing suicide while in jail. The story was in all the news in the summer of 2015, and there was even an HBO documentary about the incidence. Gladwell became quite angry by the event and feels the media has failed to explain what happened and why.

It’s such a complicated story that Gladwell doesn’t even get to Bland’s story until page 313, but when he does, it all comes together perfectly.

Many people feel society is coming apart. That politics is disintegrating our culture. That everyone is on a short fuse, overly sensitive, and too easy to take offense. That there is little honesty in the world, and too many people want to carry guns. Our society is being overrun by mistrust and resentment. I am reminded of an experiment I heard about in school back in the 1960s. It involved cramming rats into a cage to simulate overpopulation. The stress of being forced to interact made them go mad and attack each other. Gladwell doesn’t mention this, but I was reminded of it constantly as I read his book.

Gladwell says we don’t know how to talk to strangers. He then goes on using various famous historical and news events to explain how miscommunication created extreme problems, often resulting in lethal consequences. His examples are quite fascinating. The first goes all the way back to Hernán Cortés meeting the Aztec ruler Montezuma, an extreme case of strangers meeting. Then he deals with Cuban spies and the CIA. This chapter is a mind-blower because Gladwell presents several historical cases where the CIA were completely fooled by double-agents. This is impressive because we assume CIA agents are highly trained at observing and understanding people.

After covering the CIA’s failure to detect traitors, Gladwell goes into detail about how Neville Chamberlain totally misread Adolph Hitler. These are fascinating cases of how we misread strangers, but they are so varied that you have to wonder what they mean to Sandra Bland’s case. Gladwell reminds us occasionally that Bland is his real goal, but he also tells us we’re not ready yet. He was right. You really want to stick close to Gladwell’s examples and explanations, because they do pay off big.

The problem is most people default to the truth, which is Gladwell’s way of saying we tend to believe other people are telling the truth. After reading his studies you feel like you should distrust everyone. Gladwell then gives cases of people who are always wary, and this is actually a worse way to live. To complicate matters, he gives several cases, such as Amanda Knox’s and Bernie Madoff’s where people act contrary to how they should act, which makes them even harder to read. I’ve seen a lot of news stories and documentaries about both of these cases and they don’t get to the details and insights that Gladwell does. I get the feeling that Gladwell wrote Talking to Strangers to show us how we’re all thinking too simplistically.

I’m not going to reiterate all of Gladwell’s arguments and cases. Besides not being able to tell when people are lying, and for many reasons, Gladwell gets to two other important insights. Coupling and location. He uses Sylvia Plath’s suicide and various studies on crime reduction methods to explain them. This is where Gladwell’s insights get more subtle. We want problems explained with one answer. Gladwell teaches us that sometimes a problem requires multiple datasets to understand what’s really going on. All too often we jump to what we think is the obvious conclusion when were missing whole areas of evidence. Evidence that sometimes appears to have no connection to the case.

Talking to Strangers is not a book you want to read casually, although it is very easy and entertaining to read. In essence, Gladwell is being a Zen master trying to explain the sound of one hand clapping. His examples bring us to the point where we have to have our own “I see!” moment. He can’t tell us. When Gladwell finally gets down to explaining what happened with Sandra Bland you should come to the conclusion that our present-day problems can’t be explained with the kind of logic we ordinary use with our friends or the kind of thinking we hear from pundits on TV. We’re too quick to lap up easy answers.

The trouble is most people will never understand what Gladwell is teaching. Most of us will continue to act on instinct using very limited instinctive thinking. Humans can’t handle the truth. This is my conclusion, not Gladwell’s. We think we know when we don’t. In fact, too many people are absolutely certain of their conclusions because their own explanations feel so right. We all live in the film Rashomon, each thinking we see the truth, but can’t understand the multiplex view we’d get from watching our lives from an outside vantage point.

Talking to Strangers, like other Gladwell books, are ones we should reread periodically. It’s so easy to fall back into simplex thinking. One of my favorite novels is Empire Star by Samuel R. Delany. It’s a science fiction novel about a farm boy from a backward planet traveling to other worlds and cultures. Before he leaves a wise person tells him that there are three kinds of thinking: simplex, complex, and multiplex. What this kid learns is most people are stuck in simplex and maybe complex thinking, and very few achieve multiplex thought. The story is about the kid evolving through the three stages of thinking.

Talking to Strangers is Gladwell’s attempt to get us to think in multiplexity.

JWH