by James Wallace Harris, Wednesday, January 3, 2018

Years ago, after reading Outliers by Malcolm Gladwell I contemplated how my life had been shaped by not having a mentor growing up. Looking back now, I see I had mentor-like encounters. My reading was guided by random external influences and that worked as a kind of mentorship. We expect teachers to be mentors, but they can’t, not really, not with so many students.

This is going to be a long essay to explain how I select books today to read and why. I feel compelled to jump back and write a history of my evolution of discovering what to read. Looking back, I wish I had known right from the first that some books are significantly better than others — that I should seek out the best. I also wish I had read from a wider range of subjects — that I could have had far more favorite subjects. And I wished I had learned at an early age that some books can be like junk food — making me addictive to empty calories.

Society expects schools to pick the best books for children, but I always rebelled against their choices. How can we raise kids to be better book selectors?

Can teachers ever select books perfectly customized for the individual student? How can teachers avoid turning off students by promoting the reading of unrelatable classics? How can parents and teachers overcome the urge to make kids read the books they loved so passionately but might not be relevant to their children’s lives? If only one book is taught in any given class period what are the odds that all the students will respond to it? Is the goal to teach reading – the ability to decipher fiction and nonfiction – or to teach kids how to find the right book that will provide them cognitive maps to reality? Are kids ever taught the dangers of reading? Are they ever warned that books can become a crippling addiction? Are they ever taught that books can spread dangerous beliefs, delusions, prejudices, hate, and lies? I wished I had learned those things early on.

It has occurred to me that how I found books have always influenced what I read. And what I read has always determined the direction of my life. Thus, I need to be more careful with how I find books. If you are not a bookworm you probably won’t understand this insight. Back in 1971 when I first took a computer course they taught us this acronym: GIGO (garbage in, garbage out). Before that, I remember hippies preaching, “You are what you eat.” From this, you might assume I’m about to write an essay on “You are what you read.” However, I’m going to take one step back and write, “You are what you find to read.”

The first book I can remember is Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson. My mother read it to me in the third grade (1959/60) after I had seen the film version with Wallace Beery. If my mother had chosen a different book for me I would have followed a different path as a bookworm? Both my parents were readers of tattered paperbacks. I remember mother reading Perry Mason and my father reading Mickey Spillane. Neither encouraged me and my sister to read. I guess they assumed our teachers would do that.

Evidently, at the end of the third grade, my teacher told my parents I had a reading problem and should attend summer school for reading. I vaguely remember going to a small, wedged shape room, probably a large closet rather than a classroom. The teacher told me to find a book and start reading. I went over to a twirling wire rack and found a small paperback titled Up Periscope. I started reading. It turns out I could read just fine. I don’t remember the summer school teacher ever giving lessons or even talking to him again. I was just bored by what they made us read in class. That twirling rack was an important book mentor and changed the direction of my life. The lesson I learned was I could pick my own books.

Starting in the 4th, 5th and 6th grades what I chose to read was determined by the school libraries and the physical locations where I came to browse. I was my own reading mentor. I remember always going to the beginning of the A’s of the kid’s section at Homestead Air Force Base Library in the 5th grade (1961/62). That got me reading Tom Swift (Appleton) and Oz books (Baum). Eventually, I worked up to the Hardy Boys (Dixon). I would have tried a greater variety of books if I hadn’t gotten hooked on series.

My sixth-grade (1962/63) teacher, Mrs. Saunders was the first teacher to be a book mentor. She’d read us books after lunch. I remember her starting A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle and me rushing to the library after school and checking out a copy to finish on my own.

When I started the 7th grade (1963/64) at another school I found When Worlds Collide (Edwin Balmer and Philip Wylie) again by browsing the beginning of a range. That simple routine was a reading mentor of sorts. By then I’d range up and down the alphabet looking for the kind of book I liked. I’d read a lot of so-so books. Books were like television or cookies, I consumed them as fast as I could. They were a commodity. I didn’t know there were great books. That’s when I could have used a reading mentor most. If only someone had only shown me how to find purpose in reading, rather than using reading for cheap thrills. If only a wise reader had shown me how to compare books to reality, or taught me about the quality of writing.

At this time I was fixated on space travel and biographies. I read for vicarious adventure. I found a numbered series that published cut-down biographies for children. I remember reading books about Ben Franklin, Aaron Burr, PT-109 and John Kennedy, and Blackjack Pershing. The numbered series acted like a mentor to me because I wanted to read them all. It also showed me that some people are more interesting than others, worthy of being written about. I wish I had had a reading mentor that that taught me that living is better than reading. On my own, I decided reading life was superior to real life.

In the 6th and 7th grade, my schools gave us order forms for Scholastic Books. I still didn’t know there was a genre called science fiction but I was drawn to science fiction books. Because of Scholastic Books, I discovered Jules Verne and H. G. Wells (too far down the alphabet to discover on my own I guess). These were the first books I bought after begging my mother to write a check. This was my first taste of owning and keeping books. I wish I had had some way of knowing what the other books were like on the Scholastic list. This was my first time I encountered a book list or publisher’s catalog. In a way, the Scholastic sales flyer was a kind of reading mentor.

If I had found different books in the As and Bs at Homestead Air Force Base Library I could have taken a different path. I picked the Oz books because of the annual showing of The Wizard of Oz on television. Now that I am older I sometimes wish I had not started down the path of fantasy stories. I can see now that I didn’t pick what I chose to read. My tastes had already been shaped by television, which makes it another kind of mentor.

The first person to truly influence my reading was my 8th grade (1964/65) teacher. I’m sad I can’t remember her name because she was very important. She had an approved reading list. To keep the grade we earned from tests during each six week period we had to read three books, three magazine articles, and three newspaper articles — otherwise, our grade was dropped one letter. We could raise our grade each period if we read five of each. Eighth grade was the year I struggled with grammar, so I was able to turn my Cs into Bs by reading. This teacher is memorable for two reasons. She introduced me to Robert A. Heinlein and got me to read books other than science fiction. She also taught me library research and how to make bibliographic lists. This teacher couldn’t be a personalized reading mentor to all her class sections, so she worked out a method of inspiring reading and allowing us to choose our own books from an approved list.

Because I asked a librarian about Heinlein, I was shown the adult science fiction section at the Homestead Air Force Base Library. It was small, only two half-height bookcases of four shelves each. Those shelves shaped my reading for a year. Again, a limited set of books becomes a reading mentor.

In the 9th grade (1965/66) I started earning money mowing lawns and babysitting. This got me into buying albums and books. Having money and a bike let me ride to used bookstores. Because I was a science fiction fan I mainly bought books from the science fiction section. I could only afford cheap books. I mainly bought ten-cent used paperbacks that were very old. That limitation was a kind of reading mentor. I mass-consumed science fiction paperbacks from the 1950s. Even today I realize that shaped my personality more than anything else.

It’s a shame I didn’t know better. I should have read more widely. In junior high, I did branch into nonfiction reading books about science, nature, space travel, exploration, history, maps, sailing, etc., but it was still a limited focus.

In the 10th grade (1966/67) I joined the Science Fiction Book Club. This defined my reading for years. Also in the 10th grade, while going to school in Mississippi that only required 16 credits to graduate, I had two library study halls in a six-period day. Science fiction was rare in Charleston, Mississippi, so I began reading more nonfiction.

In the 11th and 12th grade I worked and went to school so I stopped watching television and got little reading done. (This also became true after I got married and worked full time.) Being a bookworm requires the luxury of time.

In the 1970s while in college, I joined the Book of the Month Club and The Quality Paperback Book Club. This broadened my reading somewhat. So these book clubs became reading mentors. Book clubs allowed me to acquire hardbacks at a discount, but the two monthly selections also became a reading mentor too.

By this time I was regularly reading the science fiction magazines, F&SF, Analog, Galaxy, If, Amazing, and Fantastic. These periodicals had book reviews, and they became another reading mentor. In the late 1960s or early 1970s, I read a review of Heinlein in Dimension by Alexei Panshin. That started me reading books about books. However, I seldom branched out of science fiction. It wasn’t until I became an English major in the later 1970s that I began studying books outside the genre. But even then I rebelled against what my professors wanted me to read. For every required classic I was forced to read to pass a test, I read ten or twenty books of my own choosing.

Unfortunately, most of the books I chose were science fiction, with a smattering of popular science and biographies. Now let’s jump ahead about thirty years. Amazon.com changed my reading habits a lot. But what really changed my reading habits was Audible.com. From listening to books read by wonderful narrators I learned I was a very poor reader myself. I also discovered my poor reading habits caused me to read too fast and love books that could be read fast. Once I started listening to books I tried all kinds of novels and nonfiction I would never have enjoyed before. Suddenly, I loved 19th-century novels. Ones that previously had turned me off by all the slow tedious descriptive bits. I also got into long rambling nonfiction books.

I have to say audiobooks have been my best reading mentor. I was reading around 12-20 books a year during the 1980s and 1990s. Mainly because of work and being married. From 1963-1973 I probably read several books a week. From 2002-2017 I read one book a week, or about 52 a year, mostly because of Audible.com. Not only did I read (listen) to more books, my range of reading topics exploded like a nova.

Then around ten years ago, I started blogging and writing about books. I began to think more about what reading meant. I read more book reviews. The internet gave me access to book commentary from all over the globe. I read blogs by other bookworms and discovered whole reading vistas I had missed. Sites devoted to books and reading maniacs showed me countless paths other bookworms had taken.

Since the 1980s I’ve been fascinated by meta-lists. I created one for science fiction, first for a fanzine, and then for the internet. Since then I’ve found others creating general fiction meta-lists, like The Greatest Books, or even collections of meta-lists like Worlds Without End. These are another kind of reading mentor.

Then there is Goodreads and Listopia where millions of readers gather to discuss books. I can even browse what books family, friends, strangers, and famous people read. That’s another kind of mentor.

Finally, in recent years I’ve been greatly influenced by Best-Books-of-the-Year lists, and especially meta-lists that collect them all together. For example, here is “The Ultimate Best Books of 2017 List,” a meta-list created by Emily Temple, where she combined 35 lists covering 520 different recommended books. These annual lists have been getting me to read 6-10 books each year I never would have tried before, and often they turn out to be the very best books I read in the year.

In conjunction with the Best-of-the-Year meta-lists is ebook bargain sales. I subscribe to a half-dozen email newsletters that tell me what books are on sale each day as ebooks. I’ve already bought three books from Temple’s 2017 list. It’s hard to resist trying a book that is on ten or more Best-Books-of-the-Year lists for only $1.99. That makes for a powerful reading mentor.

It turns out the wisdom of crowds is true. It might make the best reading mentor of all I believe. I would think if kids in school had access to meta-lists of books kids like themselves were recommending it might be an excellent mentor to aid teachers.

It would be great to have had a human reading mentor growing up. To be honest, I was never trustful of grownups as a kid. I was a know-it-all little schmuck who wanted to make my own decisions, even if they were bad. I was greatly inspired by my peers, but let’s be truthful here too, my peers were not that wise. We were all too influenced by trends. Plus, I became addicted to science fiction at an early age, which made me ignore most everything else to read.

A while back I wrote, “What 12 Books Would You Give Your 12-Year-Old Self.” Even if I had a time machine I doubt I could have been much of a mentor to my younger self. We all wish we had known what we know now back then, but we forget that most of us are hard of hearing when it comes to taking advice. Today’s kids seem more connected to their parents than kids of my generation. Maybe today parents can be mentors. Rich folks have always been great mentors to their children. I do believe Malcolm Gladwell was right in Outliers that the kids who succeed in life start early and have mentors.

We try to design education curriculums that has the wisdom of mentors, but I’m not sure if such one-size teaches all plans can ever succeed. We know the internet inspires both good and bad in children but will we ever be able to channel its chaos? I wonder if kids can find other kids on the internet who could act as their reading mentors and provide the kind of wisdom I missed growing up. Teachers might try to catalog the best young adult bloggers to show their students. And I assume the internet allows teachers to be far more in tune with their students than teachers of my era.

JWH

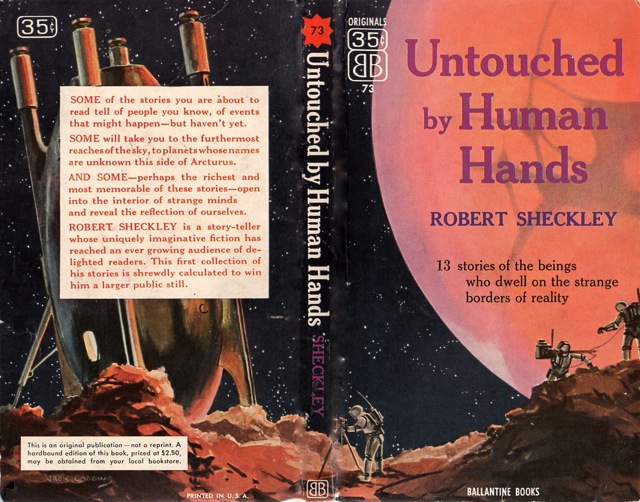

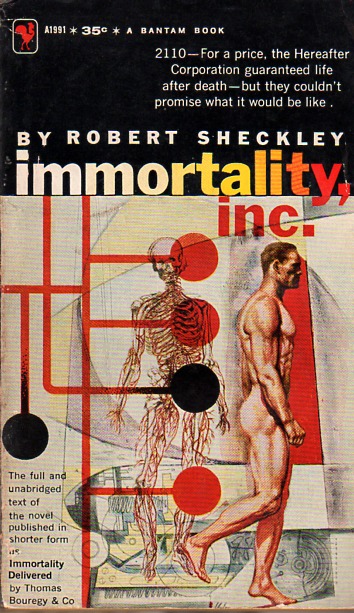

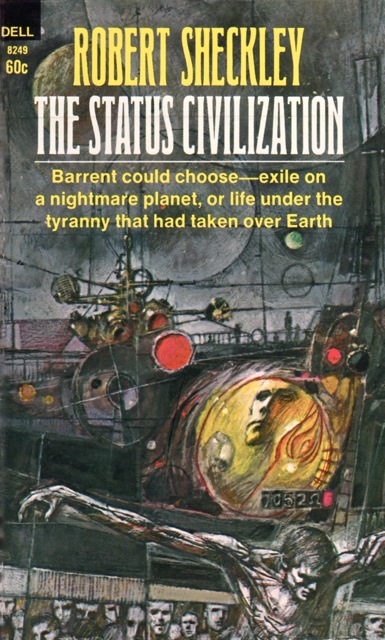

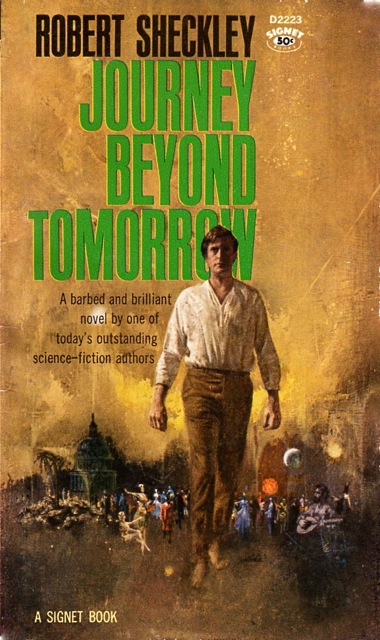

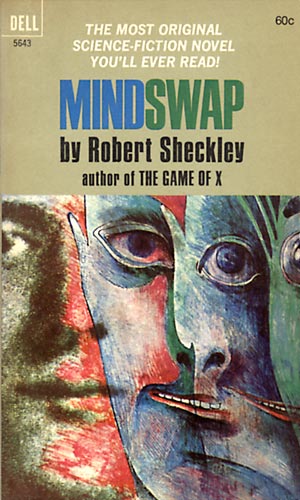

Monday, my buddy Mike and I were going up and down the isles of the science fiction section at Barnes & Noble looking to see if our old favorites were on the shelves. There were a few books each for Heinlein, Asimov, and Clarke, the Big Three SF writers of our childhood. But for many of the classic SF authors that we fondly remembered, none of their books were available. The last writer I looked up was Robert Sheckley. No luck. It’s sad to think modern readers won’t be discovering Mindswap or Untouched by Human Hands.

Monday, my buddy Mike and I were going up and down the isles of the science fiction section at Barnes & Noble looking to see if our old favorites were on the shelves. There were a few books each for Heinlein, Asimov, and Clarke, the Big Three SF writers of our childhood. But for many of the classic SF authors that we fondly remembered, none of their books were available. The last writer I looked up was Robert Sheckley. No luck. It’s sad to think modern readers won’t be discovering Mindswap or Untouched by Human Hands.