by James Wallace Harris, 1/14/25

This essay is about memory and history. What can I remember? What can I document with photographs or research with Ancestry.com? What can I find on the internet? I want to know as much as possible about Helen Harris. I plan to update this page as I find more information. The photo on the left at the top of the page is me with my grandmother around 1953. I was her first grandchild. The next photograph is of my grandmother with me and my sister in 1959. The last picture is just the best portrait I have of her. I believe it was taken in the 1960s.

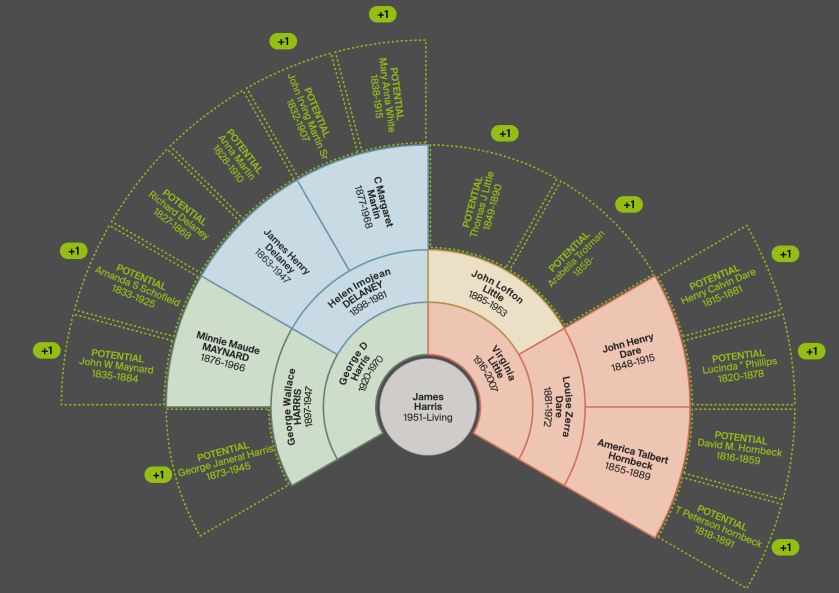

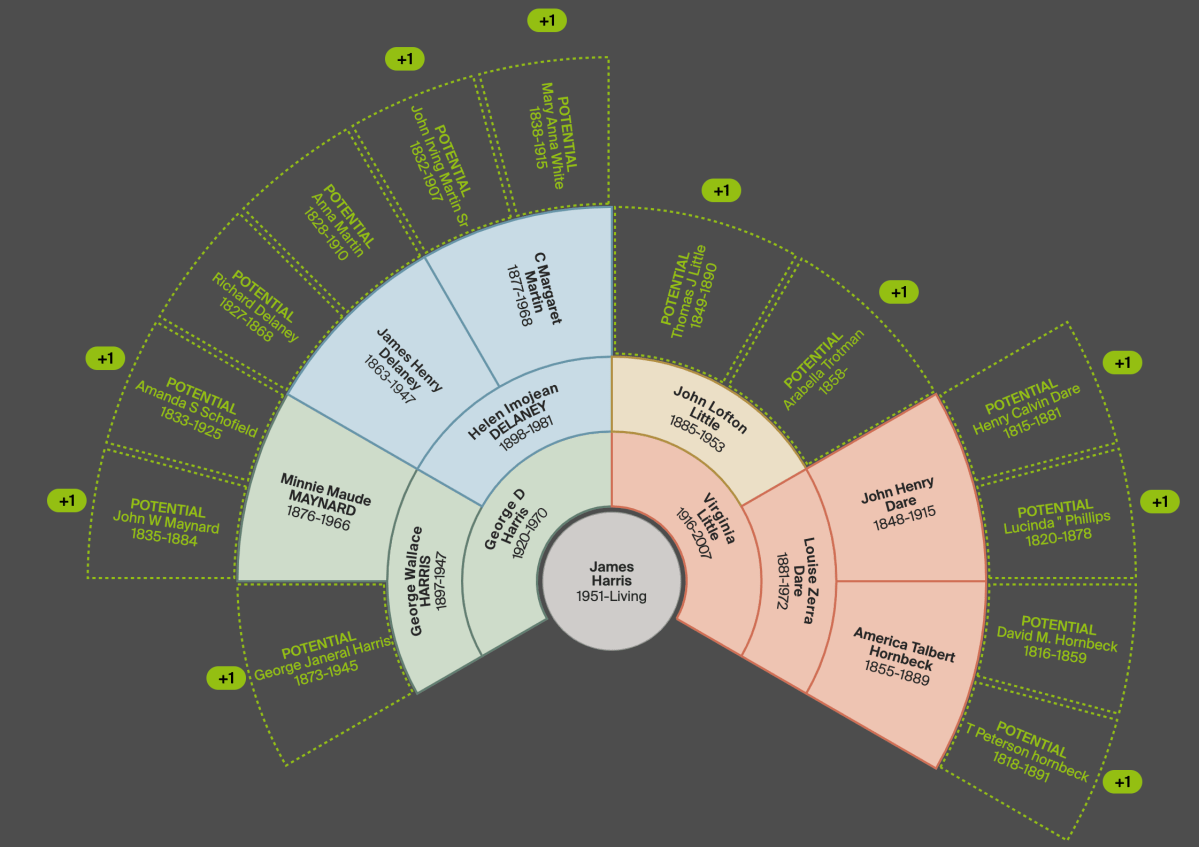

Helen Harris was my grandmother, my father’s mother. I’m learning to use Ancestry.com by researching her records. This essay aims to show how genealogy research works and to push my memory to remember everything I can about my paternal grandmother. I’m also using clues I found on Ancestry.com to research on Google. Here is the current state of my family tree.

I’m going to start with my grandmother’s birth and work forward in time.

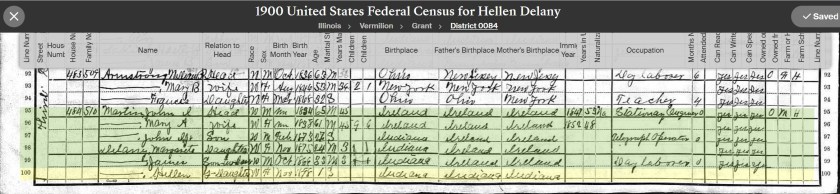

1900 United States Federal Census (June 20, 1900)

I cannot find a birth certificate for my grandmother. I discovered on Google that Indiana didn’t require birth certificates until 1907 (but some counties had them as early as 1882). I’m not exactly sure where my grandmother was born. The first official document that lists my grandmother is the 1900 United States Federal Census.

Helen is listed as a granddaughter living with John I. Martin and Mary A. Martin, her maternal grandparents. My grandmother’s mother is listed as Margarete Delany and her father James Delany lived with them. Delaney was spelled without the e. Spellings, especially first and last names were often inconsistent in historical documents.

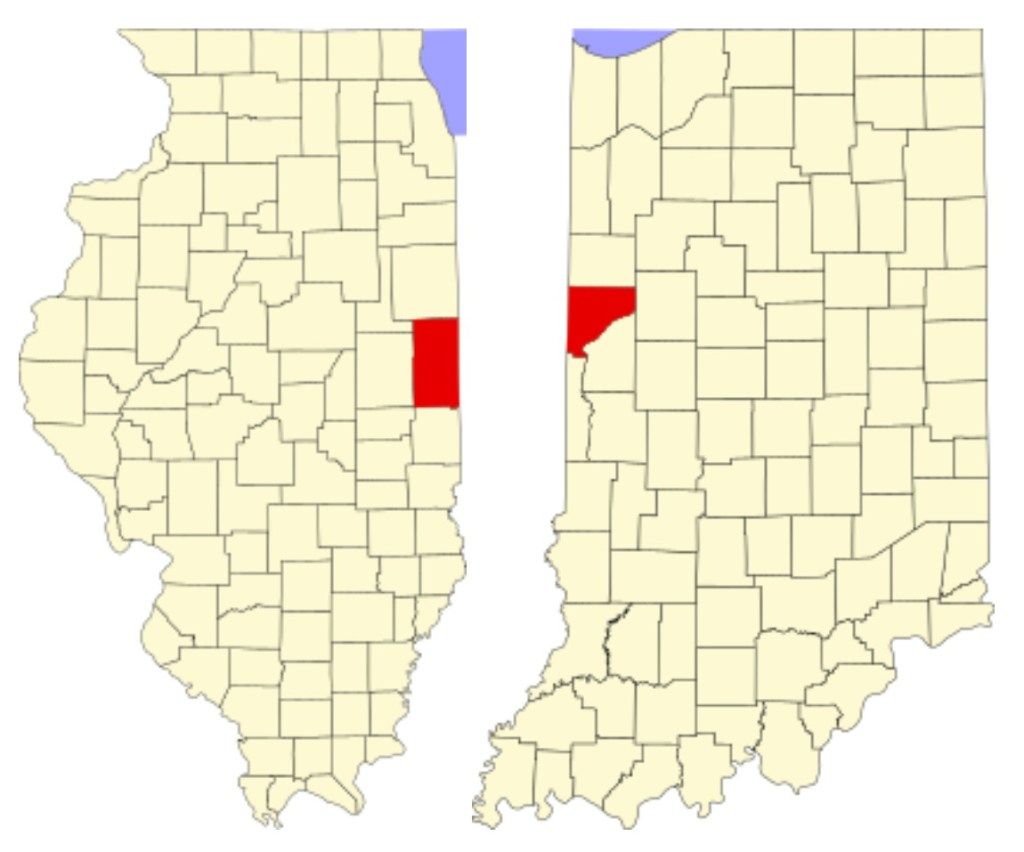

They lived on 484 Third Street, Hoopeston, Grant Township, Vermilion County, Illinois. The census was taken on June 20, 1900. My grandmother’s grandfather was born in Ireland in 1848. His wife came from Ireland in 1857. I don’t know if they were married in Ireland or America. That puts me five generations from being an immigrant on that side of the family?

Third St. Hoopeston is now divided between north and south. There’s no telling where 484 would have been. This photo shows a 2024 view of 452 and 498 of N. Third. The house in the back looks old. Maybe 498 could have once been 484?

This is about where 484 S. Third Street should be.

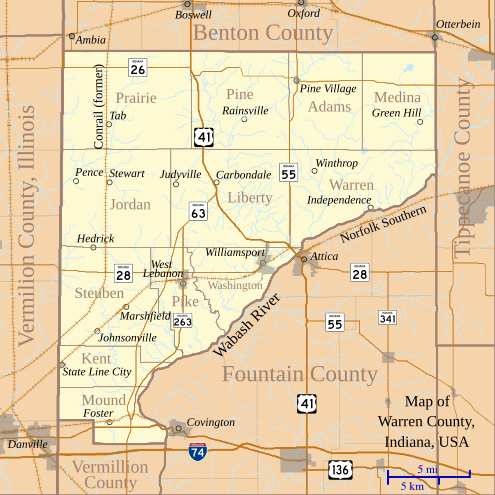

This brings up the question: Why was my grandmother living in Illinois at one year and seven months when she was born in Indiana? Vermilion County is right on the border with Warren County, Indiana. Evidently, it’s close enough for dating. I wish I knew where my grandmother was born.

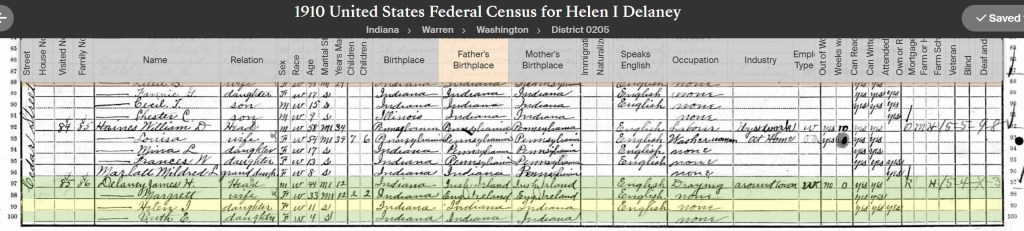

1910 United States Census (April 10, 1910)

Helen Harris was 11 and living on Cedar Street, Williamsport, Washington Township, Warren County, Indiana. Her father was listed as James H. Delaney (44) and her mother Margrett Delaney (33). My grandmother now had a 4-year-old sister Ruth. That validates real life because my grandmother had a sister Ruth. The names have different spellings. This map shows how close they were to Vermilion County, Illinois, and the location of Williamsport. In 1910, the town’s population was only around 1,200.

I was always told she was born in Indiana, but I can’t validate that in any way. Was Williamsport her birthplace and family home? Later records claim she was born Helen Imojean Delaney on November 28, 1898, to James Henry Delaney (1863-1947) and C. Margaret Martin (1877-1968). I might find out more when I research Margeret Martin.

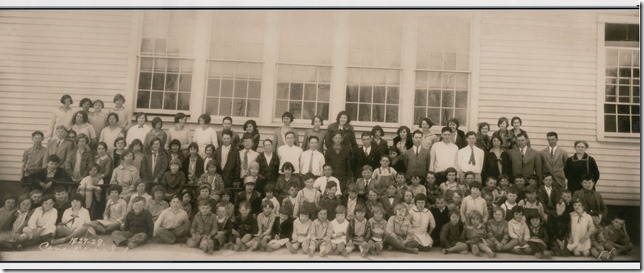

Here is a photograph from Williamsport in 1910. My grandmother would have been eleven. I wonder if she is in this group of people? How far can I go with this research? Just how many pieces of evidence of our lives do we leave behind? I wonder if I drove to Williamsport if I could find more clues?

My next bit of evidence comes from 1915. I don’t know where this clipping came from. It appears to be a look at the past. My grandmother is about 16. She’s third from left in the back, wearing the weird hat. It’s the earliest photograph I have of her. (Strangely, I also have an old newspaper photograph of my mother on a basketball team.)

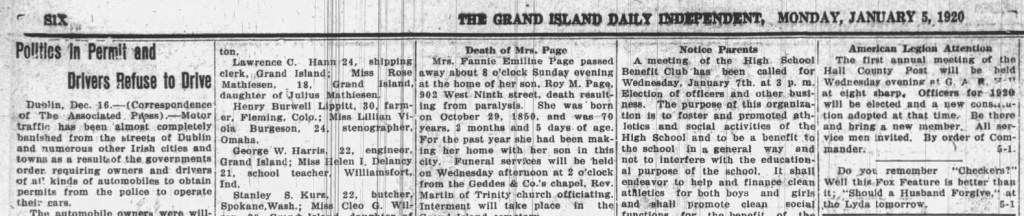

The next record I can find about my grandmother is a marriage notice in The Grand Island Daily Independent for Monday, January 5, 1920. Helen Delaney married George W. Harris, 22, an engineer. She is listed as 21 and a school teacher.

I wonder what they mean by an engineer? Was he a college graduate? After he moved to Florida, my grandfather worked as a border agent. Supposedly, his picture was once in Life Magazine arresting illegal aliens coming in by boat. My grandmother once told me she had been a schoolteacher in a one-room schoolhouse. So that fits. My father, George Delaney Harris, their first child was born on October 12, 1920.

How did she meet a man from Nebraska? This is the earliest photo I have of my paternal grandfather, George W. Harris. He is on the far right. Those are his parents and brothers, my great-great-grandparents. He looks older than 22 there, so I’m guessing it was after 1920.

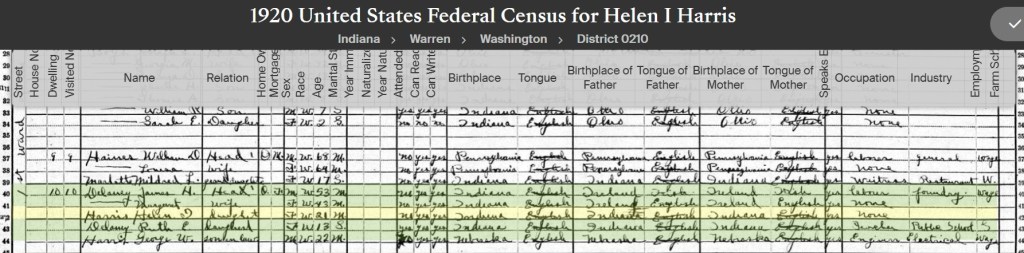

1920 United States Federal Census (June 2, 1920)

My grandmother and grandfather are living with her parents in Williamsport, Indiana. Was the Nebraska newspaper notice of their marriage just a notice, and they weren’t living in Nebraska? Or had they gone there to marry, and then returned to Indiana to live? My grandmother is unemployed, but my grandfather is now an electrical engineer.

Sometime during the 1920s, they move to Florida. I have no proof of when or where. The next record to validate their existence does put them in Florida. I’d love to know the story behind the move.

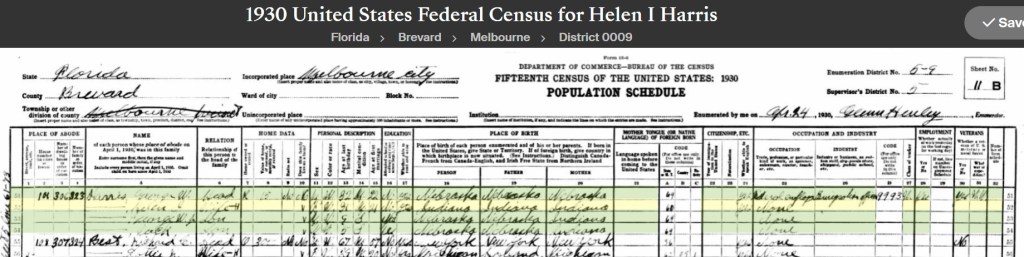

1930 United States Federal Census (April 4, 1930)

I never heard anyone in the family saying they lived in Melbourne, Florida in Brevard County. The census document says they live at 101 “Wolfe” Street. But I’m not sure of the handwriting. Can’t find a Wolfe street. My grandfather’s occupation is now listed as a federal employee and an emigration officer. That fits with family stories. My grandmother is still unemployed, but now has a second son, my uncle Jack.

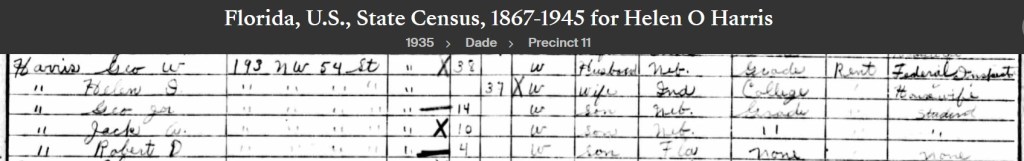

1935 Florida Dade County Census

They rented a house at 193 NW 54th St. My grandfather was a federal inspector. All three sons are now here, including my Uncle Bob. My dad was 14.

1936 City Directory

My grandmother is listed as living at 324 NW 53rd Street in Miami. Here is a current Google Maps Streetview photo. This

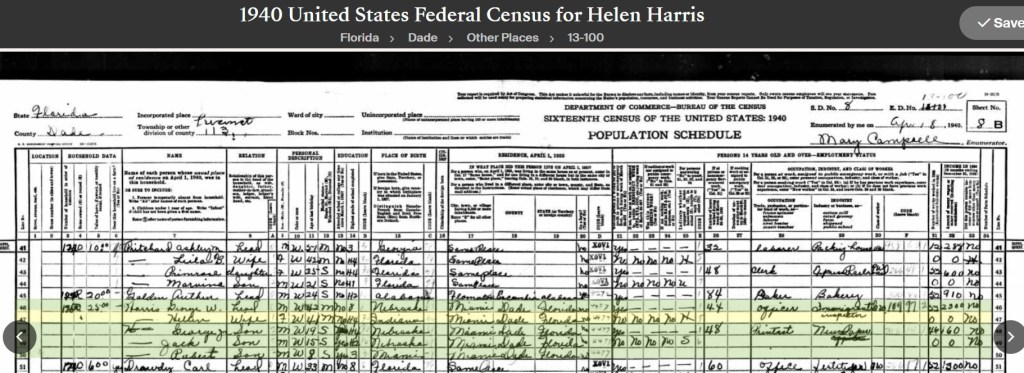

1940 United States Federal Census (April 8, 1940)

They are now living in Dade County, where Miami is located. However, I can not make out the township. I would love to know their address. I remember visiting my grandmother in a little house in the early 1950s. My grandfather had died in 1947.

My grandfather is now an Immigration Inspector, and my father, 19, works for a newspaper. I have a clipping from a Miami newspaper, describing my father studying advertising layout in high school. I won’t include it here, just evidence for my grandmother. Uncle Jack is 15 and Uncle Bob is 8. I have one photo from around this time. My Uncle Bob is in the middle, and he looks like a teen, so I’m guessing it’s around 1945?

Here’s a picture of my grandmother with my mother. My mother and father got married in 1945. I assume this photo was taken before I was born in 1951.

1953 City Directory

My grandmother is listed as living at 1131 NW 55th Terrace in Miami. I would have turned two that year. I remember visiting her in the mid-1950s, in a small house. This could have been it. Evidently, she was living alone by then. Here’s what it looks like from Google Maps Streetview. My memory is of a house on a corner surrounded by lots of trees looking like the two below.

I can’t find any more resources on Ancestry.com for my grandmother. She’s not in the 1950 United States Federal Census, and Ancestry.com doesn’t seem to have access to censuses from 1960 forward. Nor can I find any more city directories. I wonder if my grandmother didn’t fill out a 1950 census. She was a widow by then, and I assume her three boys had moved out.

My Memories

I mainly grew up around Miami Florida. That’s where my father’s side of the family had been living since the 1920s, or so I thought. However, my father and his father were from Nebraska, and his mother and family were from Indiana. I never knew how my father’s parents met. That’s the kind of mystery you wish pursuing genealogy would answer but doesn’t. My grandfather died before I was born, so I have no memory of him, and very few stories.

My earliest memory of my grandmother, Helen Harris, is visiting her in a tiny house in an old section of Miami. Back in the 1950s, Miami seemed mostly new housing divisions, but sometimes we’d visit older sections that were probably built in the 1920s or 1930s. I’d love to know where that house was located. This was probably mid 1950s.

My next memory of my grandmother was visiting her at an old apartment on 8th Avenue, which I believe is Flagler, and is now considered part of Little Havana. She was the manager, and this was in the late 1950s or early 1960s. The place was old. I loved roaming the old interior halls, with the ancient musky-smelling rugs, and talking to the old people living there.

Around 1959 my mother was diagnosed with TB and was sent to stay at a sanatorium in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. My father was in the Air Force and stationed in Canada. So my grandmother moved into our house in Hollywood, Florida to care for Becky and me for about six months. I have several memories from this time. (The center picture at the top of the page is from this time.)

After that, she moved to an apartment complex on Bayshore Avenue, right on Biscayne Bay. She stayed there, I believe until she died in 1981. But I’m not positive. My father died in 1970 and my mother, sister, and I moved to Memphis, Tennessee. I only saw my grandmother a couple more times after that when I would visit Miami to see a friend. The last time was in 1978 when I got married and took my wife Susan to meet her.

Most of the other memories I have of Helen Harris were when she came to family Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners. I did stay with her several times at the apartments on Flagler and Bayshore Drive.

I do have some specific memories. When my grandmother kept Becky and me in 1959, I was seven, and sometimes still wet the bed. She knew I admired her large leather-bound zip-up 3-ring notebook which she used to organize all her bills and paperwork. She told me when she came that if I didn’t wet the bed while she was there she’d give me her notebook when she left. I got that notebook. My parents should have tried bribing me earlier.

One of the most exciting memories I have of my grandmother is when I stayed with her at the apartments she was managing. I had seen the 1958 movie, A Night to Remember about the Titanic, and told her about it. She introduced me to an old lady living at the apartments who had been on the Titanic as a child. Years later, I wondered if I could track down who that lady was. I don’t remember her name.

I can’t remember too many details about my grandmother’s personality. She was jolly and I loved her. She collected glass figurines of dogs, so my sister and I always gave her a little dog figurine for her birthday or Christmas. I remember seeing her several times reading a book about the medicinal value of honey. She also talked about Edgar Cayce, the psychic. I can’t remember anything else she liked. I don’t recall her watching TV, playing music, or reading novels.

In 1965, I stayed with her at the Bayshore Drive apartments. I remember helping her clean out an apartment. I found an old tackle box which she let me keep. She didn’t see that it had a switchblade knife in it. I loved that knife and took it to school with me. I never told any grownups about it. I use the tackle to fish off the sea wall. While I was staying with her I would gather coconuts and unhusk them. I sold a dozen coconuts to a vegetable stand in Homestead for 50 cents each.

I remember she had friends named John and Alice. I believe we rented their house for a couple months in 1958 before we moved into our house in Hollywood, Florida. I think this might be Alice and John on the left, but I’m not sure. The other man was named Ollie. But that’s all I know.

The next photo might be the last photo I have of my grandmother. I believe it’s with her sister Ruth but it might be Alice. It was taken at the Bayshore Drive apartments, I believe in the 1970s. The last time I visited my grandmother was in 1978. I had just married Susan and we had gone down to Miami so I could introduce her to my grandmother.

Helen Harris died in 1981. I regret not calling or writing her more. If I had known I would one day be writing this essay I would have asked her a lot more questions. And I would have saved more documentation.

The faithful believe they will be reunited in heaven with their loved ones. That would be nice, but I’m not a believer. We’re often told that those who pass will live as long as someone remembers them. Helen Harris might be down to three people who remember her, maybe four. If by chance you do, leave a comment. I might have hordes of unknown relatives that remember her.

One last memory. Once my grandmother told me about her high school class. It was small. I want to say thirty people. She said they had agreed to a tontine, and the last person living would get some object I’ve now forgotten. Over the years, I wonder who won the tontine. I wonder if genealogy research could lead me to her graduation class.

We leave behind very little which proves that we were once here. Eventually, it all fades away.

JWH

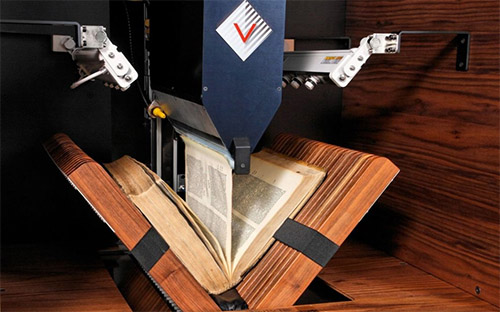

Most of us do not have evidence that will matter to historians, but you never know. And even if we did, how do we pass it on? If you’re a famous person you can donate your papers to a library. One thing us ordinary folks can do is to share photographs with relatives, or anyone who is pictured in the photographs. I have some old school yearbooks that I’m going to scan and upload to the Internet Archive.

Most of us do not have evidence that will matter to historians, but you never know. And even if we did, how do we pass it on? If you’re a famous person you can donate your papers to a library. One thing us ordinary folks can do is to share photographs with relatives, or anyone who is pictured in the photographs. I have some old school yearbooks that I’m going to scan and upload to the Internet Archive.