by James Wallace Harris, 7/17/24

Susan and I are watching the entire run of Leave It to Beaver. We’re currently in the sixth and final season, about to finish all 234 episodes. We watch two episodes a night, so that means we’ll complete six years of the original broadcast in 117 days. Back then they had thirty-nine episodes per season.

We’ve watched Jerry Mathers (Beaver) and Tony Dow (Wally) grow up. When the series begun in 1957, Beaver was seven and in second grade. Wally was thirteen in the eighth grade. Six years apart, but six years later, Beaver was in the eighth, but Wally was in the twelfth, four years apart. Evidently, the producers didn’t want Wally going off to college. Mathers and Dow were only three years apart in age in real life. Dow was born in 1945, and Mathers in 1948.

Leave It to Beaver premiered on October 4, 1957, the same day that Sputnik I went into orbit. I had just entered first grade and was five. I don’t remember seeing Leave It to Beaver as a kid in the 1950s. It wasn’t until sometime in the 1960s that I saw an episode, and I didn’t see it often. Susan didn’t watch it as a kid either.

In other words, we’re not watching Leave It to Beaver for nostalgic reasons. I’m not sure why we got hooked on it. We were just looking around for something to watch, and I suggested the show as something pleasant we both might like. Susan doesn’t like shows with violence (although I’ve got her to watch the Fargo series recently). I think I picked Beaver because Susan loved watching Andy Griffith so much.

I do have nostalgic memories of family shows like Make Room for Daddy, Father Knows Best, The Donna Reed Show, The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, and My Three Sons from the late 1950s and early 1960s, so it’s odd we picked Leave It to Beaver. We even signed up for Peacock with no ads so we could watch it without ads.

I can’t promise that Leave It to Beaver is one of the greatest TV shows ever. It’s pleasant. We like the actors and characters. The stories are quite simple, very pro-family, very didactic. The stories are also repetitive. For example, there are several episodes about Beaver getting a pet he can’t keep, including an alligator, rat, donkey, and a very ugly monkey. There were many shows where Beaver friends convince him they should all go to school wearing something weird, like a sweatshirt with a horrible monster on it, or show up for a special event not wearing a coat and tie, and Beaver shows up as the gang planned but the others don’t, making him look stupid. Another common plot was for Beaver’s friends to talk him into doing something he shouldn’t.

Most of the episodes had a message. Often it was: When your parents tell you something it is for your own good. But fairly frequently, there were shows about how parents should listen to their kids sometimes, because sometimes their kids knew better.

I remember Leave It to Beaver being about only the kids, sort of like Peanuts. But half the show is about Ward and June. I guess as a kid I just didn’t pay attention to adults, either in real life or on TV.

One of my favorite episodes has Beaver getting in an argument with a bigger kid and uses a cuss word. Of course, the school bell rings when Beaver says the word, but his teacher, Miss Landers, heard what he said. Miss Landers is shocked and sternly informs Beaver he’s in big trouble. Miss Landers tells Beaver to bring a guardian to school to meet with her. Ward is off on a business trip, and Beaver can’t bring himself to tell June what he said, so he convinces Wally to come to school as his guardian. Miss Landers accepts Wally because she doesn’t want Beaver to tell June what he said either.

Even though we time travel back to the 1950s and early 1960s when we watch Leave It to Beaver, it doesn’t feel nostalgic. It feels more archeological. The show just reminds me of how things were so different back then.

I thought I’d find episodes I would remember but I haven’t. The closest any episode felt like I had seen it before was the one when Beaver and Wally play the stock market. I do remember as a kid watching a TV show where the kids learn about the stock market, but I can’t swear it was on Leave It to Beaver. Maybe it was, maybe it wasn’t.

Quite often while watching other old TV shows I’ll tell Susan, “Oh, I’ve seen this one.” But that’s never happened with Beaver. But the intros and closing credit scenes to all six seasons seem burned into my memory, but not the stories themselves. I guess I remember the visuals and not the plots.

It’s weird to watch a show from the first to the last episode. I’ve done that several times now. It’s also kind of painful. Older TV shows depended on every episode being entirely self-contained. This approach leant itself to formulaic scripts, which was true with Leave It to Beaver. I’ve read that Beaver was the first show to have a finale, which was a unique episode. But for the most part, there was a commonality to every other episode.

As far as I can remember every episode featured the staircase. Most featured front or back door meetings, breakfast table meetings, dinner table meetings, doing the dishes together, sitting around the bedroom, living room, or den. For most seasons we saw Ward and June kiss in each episode. That seemed to fall off in the last couple of seasons. All four of the main actors had standard facial expressions and used specific body language in every show.

One thing I remembered wrong was the Eddie Haskell (Ken Osmond) character. I remember him as a juvenile delinquent, the bad boy. But the show portrays him as a sympathetic loser, on the pathetic side, one who tries too hard, has too much ego, and probably has bad parents.

Beaver had very few guest stars, which was what I enjoyed when watching the entire nine years of Perry Mason. However, a few of the actors, like Miss Landers (Sue Randall) I’ve seen on other shows. I saw her on Perry Mason. Of course, Fred Rutherford (Richard Deacon) went on to be Mel on The Dick Van Dyke Show.

Watching old TV shows from the 1950s and 1960s reveals an alternate reality that we all observed back then. The Beaver often mentioned the TV shows that were on when Leave It to Beaver was on the air, even making inside jokes about the competition. And to a degree it makes fun of other pop culture of the 1950s and 1960s. But it was very gentle. I even saw a science fiction magazine a couple of times. I’ve often wondered when science fiction was first mentioned in pop culture.

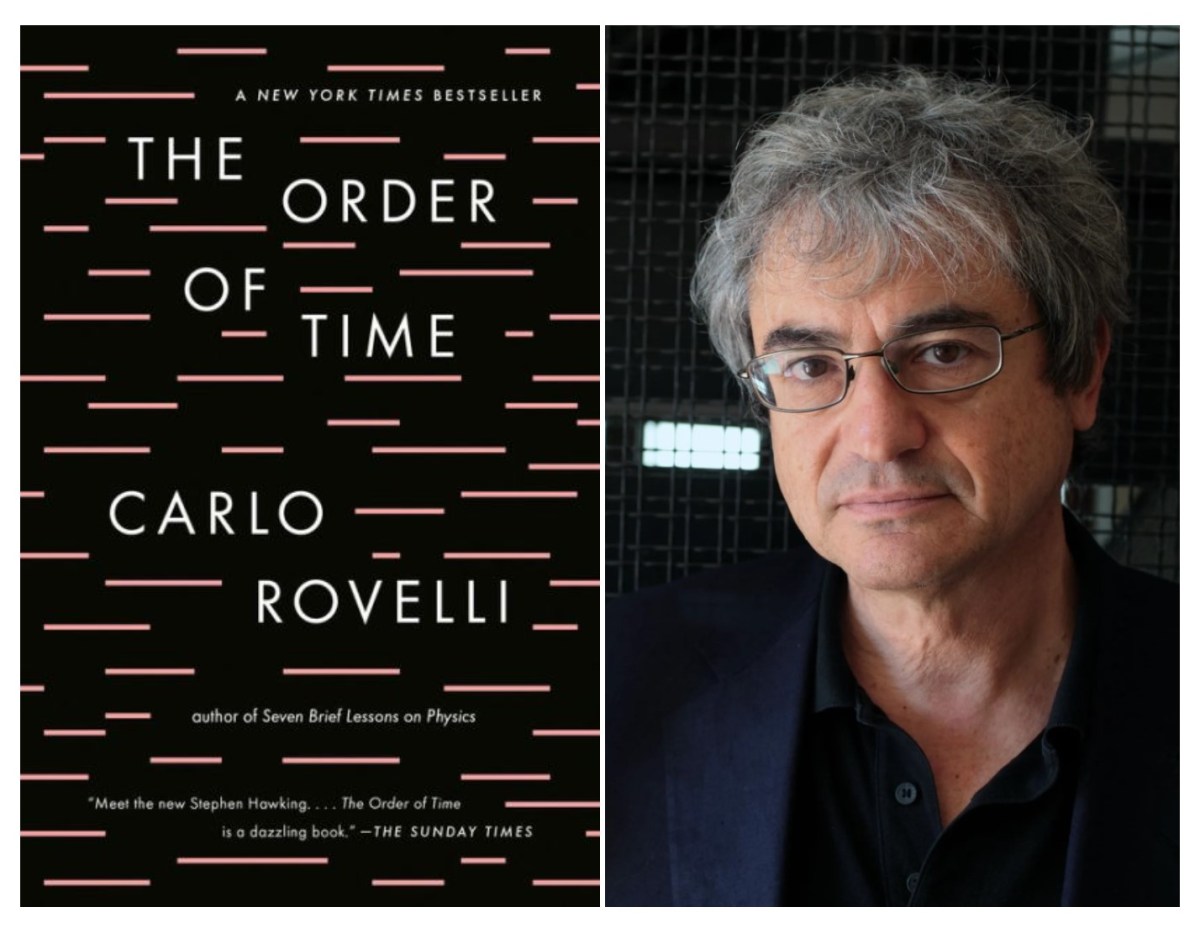

The show covered the phases of childhood and adolescence that kids were going through back in the 1950s and early 1960s. Leave It to Beaver went off the air in 1963, before the famous Sixties began. This photo meme on Facebook conveys that stark change perfectly.

Watching Leave It to Beaver explores the times before that cultural shift.

JWH