Yesterday I got in a Blu-ray copy of The Big Trail, an early widescreen movie from 1930. The Big Trail has quite a fascinating history behind it. Starting in the late 1920s Hollywood began experimenting with widescreen and Technicolor, but the depression killed off interest in these technologies, especially widescreen because it required special theaters, screens and projectors. The Big Trail was filmed from April to August in 1930 in black and white using both 70mm and 35mm cameras, creating two unique versions from different camera angles. The whole production was also shot in five languages using different lineup of actors for each language.

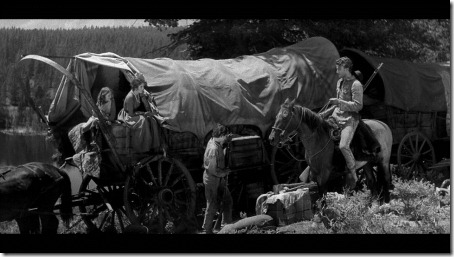

Epic production doesn’t begin to describe the making of The Big Trail. Seven different states were used for film locations, covering 4,300 miles, traveling in 123 baggage cars, with 93 principle actors, 2,000 extras at all the locations, 725 Indians from five tribes, 12 Indian guides, 22 cameramen, 1,800 cattle, 1,400 horses, 500 buffalo, 185 wagons and a production staff of 200. And they had the wagon train do everything wagon trains did back in those pioneering days, cross rivers, get lowered down cliffs, blaze trails through timbered lands, cross deserts, climb mountains, survive snow storms. All other wagon train movies since have been puny in scale. The Big Trail was a very gigantic production, but it’s not as famous as Gone With the Wind from 1939. That’s too bad, it should be better remembered.

I had to watch The Big Trail alone last night because none of my movie friends like old black and white films and I couldn’t convince them to give The Big Trail a try. What a loss for them. It’s a shame because as soon as I started up The Big Trail I was stunned by it’s beauty. Old movies are in a square format and seeing this movie in widescreen format on my 56” HDTV made my heart ache. If only this 70mm widescreen format had caught on in 1930. All my favorite old films from the 1930s and 1940s would have been so much more grandeur looking. And that’s what Fox called their experimental format, the “Fox Grandeur” process. What if Grand Hotel had been widescreen, or The Maltese Falcon, or The Wizard of Oz, just imagine how more magnificent they would have been.

[This screenshot is from Blu-ray.com – click for full size version]

Modern movie goers are used to high tech visual productions and when they see old movies, especially silent films and films from the 1930s, they think of them as primitive and crude, and often assume people of those days saw what we see today. Their technology was older and less sophisticated, but the prints we have are old and in bad shape compared to the original pristine prints audiences viewed in their day. Silent movie film goers didn’t see jerky prints with faded splotches and lines running through them. They were sharp and vivid with wonderful contrast and the motion was as natural as modern films. Sure the acting style is strange to us, but the acting style was normal to them. It was great acting by the way they judged acting.

Old movies are being restored all the time now, especially for the Turner Classic Movie crowd and Blu-ray movie fans. The restoration of The Big Trail is far from perfect, but I found it impressive to watch visually. I expect someday that digital processing will clean up even more of these film defects, and created a print closer to the 1930 original. For the most part the defects weren’t distracting. A couple of times I thought it was raining because of the tiny scratches.

The Big Trail was an experiment in many ways, not only for the widescreen filming. It was an early epic western about settlers crossing the country in a huge wagon train. The Big Trail was the first starring role for John Wayne, but many of the actors were from Broadway, because it was an early talky and they needed actors that could project their voices to outdoor microphones. Much of the dialog is stagey, and the cinematography is reminiscent of great silent films. Yet, the sets and costumes look very realistic. It would take another 60 years before citizens of the pioneering west looked so realistically dirty and grungy. Plus the Indians were real. Often the wagons were drawn by oxen and cattle rather than horses.

[Click for full size versions. From Blu-Ray.com]

Westerns weren’t this good for a long time, not until Stagecoach, ten years later. Most westerns of that era were B movies, shot full of action, produced from very small budgets. As I watched The Big Trail, I wondered how many people living in 1930 had once traveled across the country in a wagon train. The heyday of the wagon train was from the 1840 to the 1860s, when the continental railroad was built. It was possible that some of these pioneers were still alive to verify the realism of the film. I wonder if any of them wrote about it?

Westerns today, 80 years later, often work hard to appear realistic and historical. It seems like every decade has a different view on how the old west looked. Just compare the two versions of True Grit. There’s also a difference in how violence was portrayed. In The Big Trail, John Wayne only kills one of the bad guys, and with a knife. And the bad guys were on the hesitant and cowardly side, only willing to kill when no one was looking. Nobody was a great shot either. Today’s westerns have heroes that kill as many people as a mass murderer.

The Big Trail was an innocent portrayal of pioneers. At one point the John Wayne character was telling a bunch of boys what all he learned from living with the Indians and one of the kids asked, “Did they teach you were papooses come from?” That’s about as risqué as this movie got. But it was realistic enough to show a woman nursing a baby. And I thought the love conflict was reasonably sophisticated for a movie of its time. The plot of The Big Trail was gentile and slow. I’m not sure people only used to modern films would like it. Modern audiences are addicted to fast action, fast dialog, and lots of plot twists. I’ve seen The Big Trail three times now and I’m looking forward to seeing it again. It’s a classic western, and a classic 1930s film, my two favorite genres.

JWH – 12/29/12