by James Wallace Harris, 9/7/23

Alfred Hitchcock often talked about using the concept of the MacGuffin in his films. The MacGuffin distracts the audience into thinking the movie is about one thing when it’s really about something else. In Notorious (1946) we think the movie is about Nazis in South America acquiring uranium just after WWII. Instead, it’s about fucking. I hate to use the F-word here, but it’s the most exact terminology to make my point.

Back in 1946 movies couldn’t deal directly with sex, especially intercourse. Movies had to follow certain censorship guidelines, and so did books. It wasn’t until 1959 when the laws began to change, allowing art to become more explicit. What that meant was Hitchcock couldn’t directly focus on his theme. The MacGuffin suggested that Notorious was about war criminals and Nazis and that help Hitchcock hide his intended topic from censors.

People under seventy have only vague ideas about what people from the 1940s were like. We get our ideas about life in the 1940s from movies; in the same way we get ideas about American society of the 1950s from old television shows. However, Americans weren’t like the people we saw in movies, or read about in books. 1940s Americans were quite different from 2020s Americans. When we watch old movies from the 1940s, we must remember the censors wanted us to think one thing, the filmmakers another, and the actual reality of American lives were quite different still. There was far more sex going on, of all kinds, and persuasions.

Alfred Hitchcock uses Notorious to observe a very particular thing about Americans in 1946. Alicia Huberman (Ingrid Bergman) is the daughter of a Nazi war criminal who has just been sentence to twenty years in jail. A government agent, T. R. Devlin (Cary Grant) wants to use Alicia to infiltrate a Nazi plot in Rio de Janeiro. The government knows two things about Alicia. Because they bugged her conversations with her father, they know she’s pro-American and against the Nazis. Because they also know she regularly sleeps around and is alcoholic that she might be willing to do anything they ask. This is where the film title comes from, her notorious reputation.

Devlin contacts Alicia and Alicia falls in love with him because he appears to accept her as she is. She cuts back on her drinking and stops her cynical jaded sniping. Then Devlin tells her why they met and introduces her to his boss. This is when Alicia finds out that the American government wants her to seduce Alex Sebastin (Claude Rains) and get inside the Nazi organization.

This 1946 movie can’t have the feds saying, “we need you to fuck Alex Sebastin,” but the audience can read between the lines. Alicia is hurt. She can’t believe Devlin is asking this of her — doesn’t he love her? Alicia waits for him to tell her not to take the job. But Devlin wants her to say no on her own – – to prove she’s not a loose woman. Because Alicia is hurt that Devlin doesn’t stop her, she agrees to become a spy.

Throughout the rest of the movie, until near the very end, there is tension between Devlin and Alicia over her screwing Sebastian. The more Devlin becomes surlier and snarkier in his jealousy, the more Alicia applies herself to becoming the perfect Mata Hari. It’s never stated, but Hitchcock shows us the double-standard of the time. Not only are women not supposed to be sexually active outside of marriage, but they are also judged differently from men regarding what they choose to do. Audiences then, and now, would consider it nothing if a male secret agent seduced a woman spy for his country, but not for a female spy to make the same patriotic sacrifice.

Alicia rather quickly seduces Sebastian and lets Devlin know. He puts her down by suggesting a woman of her type would get the job done quickly. Eventually, Alicia marries Sebastian and goes on a honeymoon. She becomes part of his life.

I thought this part was interesting. Sebastian, the bad guy, is overjoyed to catch a woman like Alecia. He assumes she’s upright and moral. She’s younger, and quite beautiful. He is rich, suave, and sophisticated, but also shorter and much older. Sebastian and his mother totally accept Allecia into the family. On the surface, this is the path that 1940s (and 2020s) moral Americans wanted from women. The evil Nazi is proper family man, while the spies Alicia and Devlin are amoral and dishonest. What exactly is Hitchcock saying here?

At one point Sebastian sees Devlin and Alicia kissing and he’s tremendously hurt. But he doesn’t turn against her until he discovers she’s a spy. That mistake means he and his mother will be eliminated by his Nazi associates.

All through the Notorious, I wondered how Hitchcock was going to resolve his story. Not the spy story, that never mattered. It was the MacGuffin, and I knew it right from the start. If Devlin resented Alicia for fucking Sebastian and Alicia resented Devlin for arranging it, how would they ever come together?

I really didn’t want a happy conclusion to Notorious, but I knew one was coming. I wanted a 2020s realistic ending where Alicia wouldn’t forgive Devlin and tell him to fuck off in the end. However, I knew Hitchcock wouldn’t defy 1940s romantic convention in this film. He had to get Alicia and Devlin together.

In the end, Devlin admits he was wrong, and Alicia immediately forgives him. It wasn’t said directly, but I interpreted the scene to mean that Devlin apologizing for assuming Alicia would sleep with anyone because she had an active sex life. Of course, that ignores that Alicia did sleep with Sebastian, a man she previously rejected, because the American government asked. But is that the real story?

Like I said, sleeping with spies is something James Bond does all the time. I wondered if Hitchcock was also saying we should accept it when Jane Bond does it too? I doubt Hitchcock was concerned with this issue, but it’s there to consider. It’s possible that Devlin’s judging Alicia by a double standard was another MacGuffin, and Hitchcock’s real theme was about judging spies and their gender roles.

I do have another theory. Hitchcock might not care about anything we could put into words about in his films, but merely loves to create scenes with various kinds of emotional tensions to see how his audiences react to them emotionally. His films are often episodic, and he constantly plays with our reactions. Maybe the plots and themes are MacGuffins too?

JWH

While reading Davin’s history I also read “In Hiding” by Wilmar H. Shiras, which first appeared in the November 1948 issue of Astounding Science-Fiction. John W. Campbell, the conservative editor of Astounding, said this when “In Hiding” was voted 1st Place in the readers poll, “Wilmar H. Shiras sent in her first science fiction story, ‘In Hiding.’ I liked it and bought it at once. Evidently, I was not alone in liking it: it has made an exceptional showing in the Lab here—the sort of showing, in fact, that Bob Heinlein, A. E. van Vogt and Lewis Padgett made with their first yarns. I have reason to believe we’ve found a new front-rank author.” Shiras wrote four more stories in the series to create a fix-up novel, Children of the Atom (1953 Gnome Press). Many older fans fondly remember that novel, even if they didn’t know Shiras was a woman. (I thought Wilmar was the male version of Wilma.) Shiras only wrote a handful of stories after that, and then disappeared. Why?

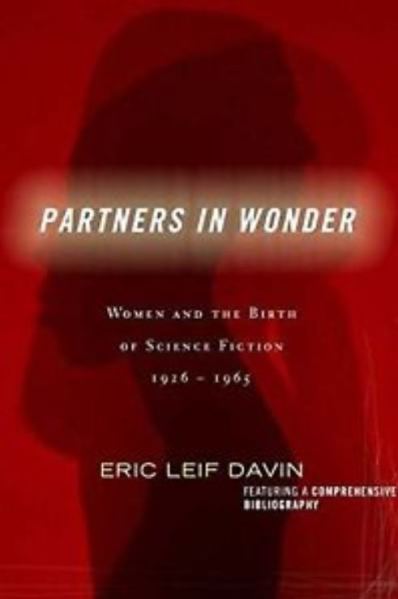

While reading Davin’s history I also read “In Hiding” by Wilmar H. Shiras, which first appeared in the November 1948 issue of Astounding Science-Fiction. John W. Campbell, the conservative editor of Astounding, said this when “In Hiding” was voted 1st Place in the readers poll, “Wilmar H. Shiras sent in her first science fiction story, ‘In Hiding.’ I liked it and bought it at once. Evidently, I was not alone in liking it: it has made an exceptional showing in the Lab here—the sort of showing, in fact, that Bob Heinlein, A. E. van Vogt and Lewis Padgett made with their first yarns. I have reason to believe we’ve found a new front-rank author.” Shiras wrote four more stories in the series to create a fix-up novel, Children of the Atom (1953 Gnome Press). Many older fans fondly remember that novel, even if they didn’t know Shiras was a woman. (I thought Wilmar was the male version of Wilma.) Shiras only wrote a handful of stories after that, and then disappeared. Why? I believe one reason young people read old science fiction is to study those changes, and study how people in the past looked at their future, our present. It’s quite revealing to learn what doesn’t change and what does, and why. Another reason to read classic SF is to search for all those pioneer women writers who were hiding in plain sight. In a recent Book Riot essay, “

I believe one reason young people read old science fiction is to study those changes, and study how people in the past looked at their future, our present. It’s quite revealing to learn what doesn’t change and what does, and why. Another reason to read classic SF is to search for all those pioneer women writers who were hiding in plain sight. In a recent Book Riot essay, “