by James Wallace Harris, 10/19/24

Technically, My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante is the first novel in a four-volume sequence that is collectively referred to as the Neapolitan Novels. Now that I’ve read all four books, I dislike that tagline for the whole story. The four books are really one whole novel, and even though Naples, Italy is very important to the story, it doesn’t properly describe the complete novel. Each volume picks up exactly where the last one stops. If they were published in one volume with no subdivisions, you wouldn’t notice any transitions.

For this review, I’m going to refer to the whole as My Brilliant Friend, and when needed, I’ll point to the individual titles as part of the story. The structure below uses the dates for the English translation. The books were originally published in Italian one year earlier.

- My Brilliant Friend (2012)

- Prologue: Eliminating All the Traces

- Childhood: The Story of Don Achille

- Adolescence: The Story of the Shoes

- The Story of a New Name (2013)

- Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay (2014)

- Middle Time

- The Story of the Lost Child (2015)

- Maturity

- Old Age: The Story of Bad Blood

- Epilogue: Restitution

Circular Plot and Recursion

The complete story begins where it ends. And throughout this long story, it constantly refers to itself. It’s so recursive that it feels like two mirrors aimed at each other. It’s also cyclical because it’s about daughters and their mothers, who eventually become mothers of daughters. In so many ways, this story mirrors its parts.

The novel is about two women, Elena Greco and Raffaella Cerullo, who call each other Lenù and Lila. The story feels like an autobiography, and we have to remember that the author’s name is Elena too. Elena Ferrante hides behind a pseudonym, but this novel feels very autobiographical. Lenù and Lila react and respond to each other so intensely that it’s hard to tell who originates what traits. I even imagined that Elena Greco is writing about two versions of her own identity, the one who writes books, and her ordinary self. And it’s interesting that Ferrante hides behind her pseudonym, claiming she wants to remain anonymous while Lila also wants to remain anonymous throughout the story. So many reflections.

Literary Novels

I’ve always thought the greatest of literary novels feel biographical or autobiographical. They don’t need to be about real people, but they do need to feel like they are, and this novel offers two realistic portraits. Another trait of great literary novel is setting. We often think of London when we think of Dickens, or Russia when we think of Tolstoy, or Ireland when we think of Joyce. Ferrante has made her book about Naples and Italy.

If you’ve only read the first volume, My Brilliant Friend, you should tell yourself that you never finished the novel. The Neapolitan Novels boxed set runs 1,965 pages. On audio the four books run 78 hours and 52 minutes. To give perspective, War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy averages about 60 hours in the various audio editions. Different translations of The Bible run 82-102 hours. The seven volumes of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past runs 154 hours and 14 minutes. In other words, the whole My Brilliant Friend is a literary heavyweight.

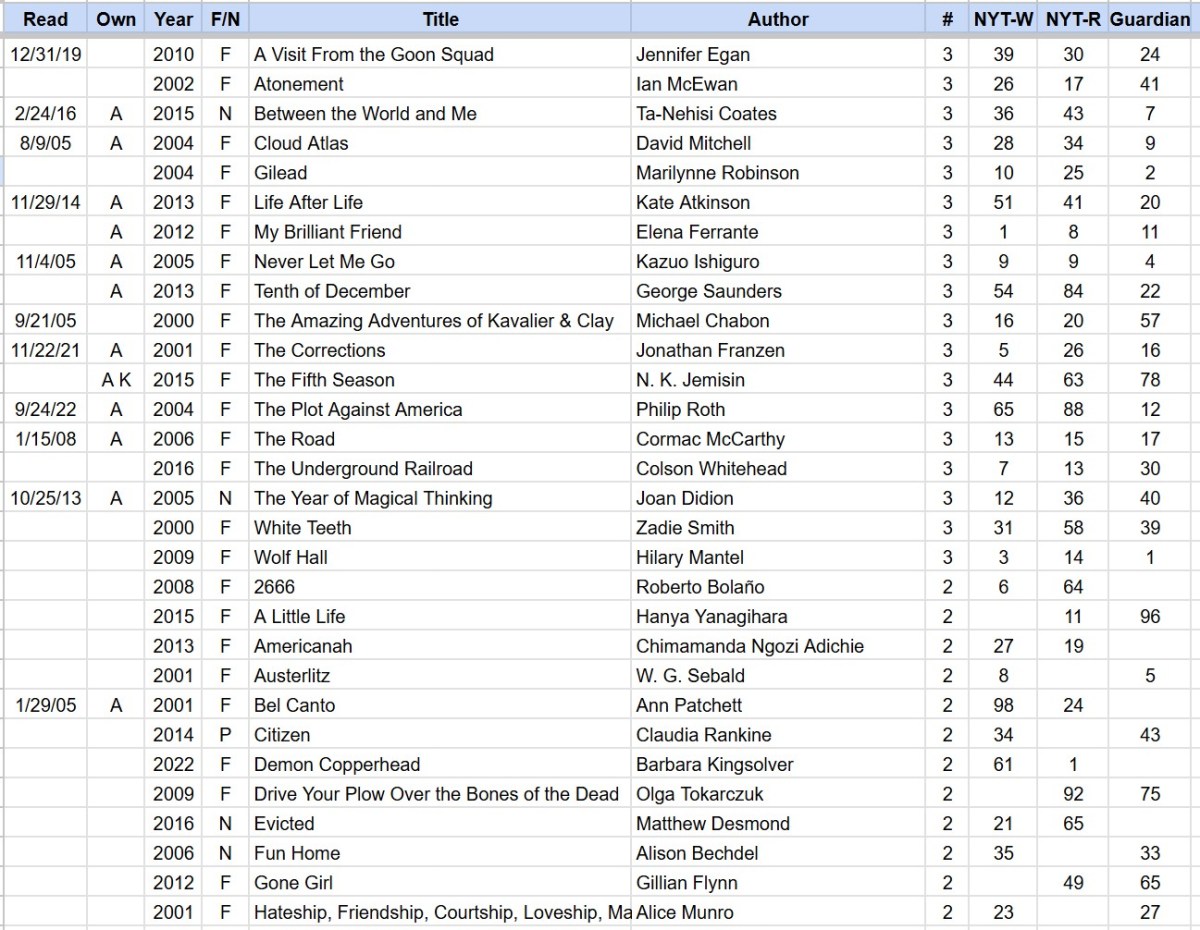

Most novels that come out in a series are never artistically heavier than a single volume. That’s why when I finished reading the single volume entitled My Brilliant Friend, I couldn’t understand why the writers polled by The New York Times considered it the top book of the 21st century so far. It was good, but not that good. That’s because it’s only one-fourth of a whole. Now that I’ve read all four volumes, I can easily see why it was voted the top novel of this century.

Will it Become a Classic?

Whenever I read a highly respective modern novel I’ve wondered if it will someday be considered a classic. I’ve never felt sure about any modern novel to predict one before. However, for the whole of My Brilliant Friend I felt like it was at least an equal to Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy. That novel only runs 36-40 hours in audio, so it’s about half the size of the full version of My Brillian Friend. The Ferrante novel is far more ambitious, at least in being a biography of two women, so maybe it needs twice the space that Tolstoy used to tell us about Anna Karenina. However, Anna is never developed in such detail like Lenù and Lila.

We follow Lenù and Lila from being little girls to old women, and that makes a huge difference in storytelling ambition. This novel is primarily about friendship, even though it says almost as much about kinship. Men do not come across well in this story. This novel is feminist at a visceral level. I’d also say this book is an anti-chemistry book in the sexual sense. Time and time again, hormones overwhelm Lenù and Lila into making bad life-changing decisions. The great loves of their lives are the same evil Mr. Right. Nino Sarratore is no Mr. Darcy. Ferrante makes Nino one of the detestable bad guys of literary history. I can’t believe that Lenù and Lila didn’t immediately recognize that he was a clone of his father, Donato, the slimy seducer they knew from childhood.

The Prose

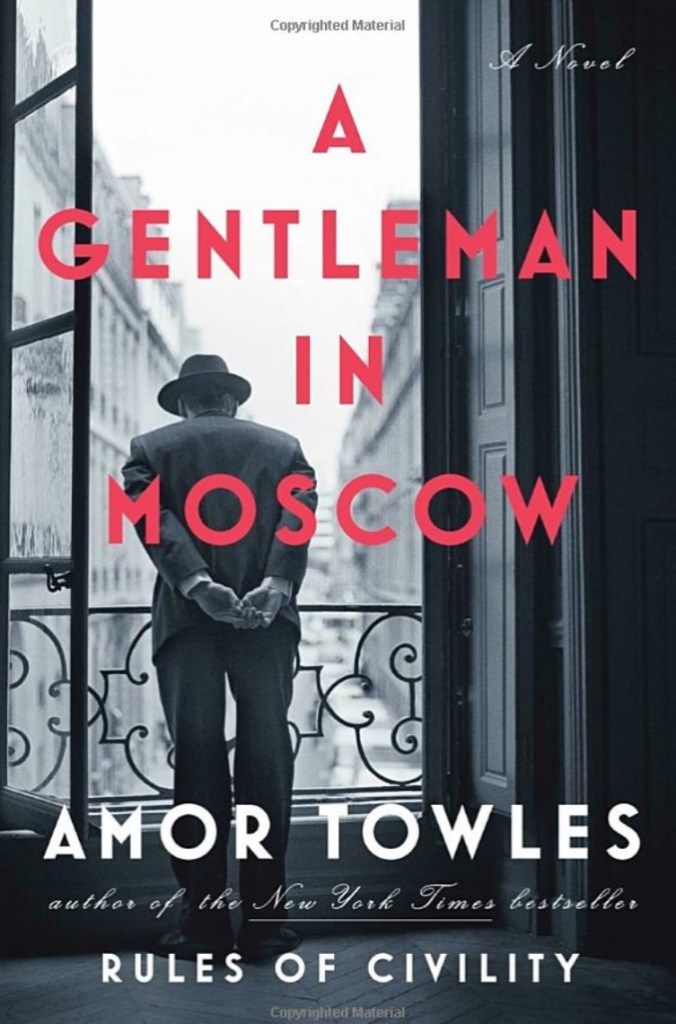

It’s hard to judge the writing of a translated novel. I do know that Ann Goldstein’s translation of Ferrante’s Italian prose is clear and precise, and the writing comes across as vivid and impactful, but the style is plain and unadorned. It lacks the colorful authorial voice of two recent novels where the prose enchanted me, A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles and Lessons in Chemistry by Bonnie Garmus. Nor does it have any the wonderful authorial commentary like old literary writers Dickens or Tolstoy since Ferrante’s story is told in the first person.

A lot of modern bestsellers have the highly refined writing style taught by MFA programs. Readability and clarity are valued over wordy digressions and colorations. This is one reason why I have a hard time predicting if a novel will become a classic a century from now. The classics we’ve crowned from the 19th century all have distinctive writer’s voices. Ferrante’s voice comes across through the characterizations of Lenù and Lila, and it’s confusing to distinguish Elena the author’s voice from Elena the character.

Final Judgment

I liked this story tremendously. It may have ruined me for reading lesser novels, especially for reading science fiction, which seldom achieves any kind of deep character development. The whole story of My Brilliant Friend reminds me of two other multi-novel sequences about characters as they age.

The first is A Dance to the Music of Time, a twelve-volume series by Anthony Powell which he wrote from 1951 to 1975 using his own life and friends for inspiration. I reviewed them here, here, and here.

And the other are books by Elizabeth Strout. Collectively, they follow the growth of two women too, Lucy Barton and Olive Kitteridge. I’ve reviewed them here.

This first reading of the entire My Brilliant Friend story will not be enough to truly appreciate this novel. Even though it’s told in a straightforward manner, it is quite complex in what it has to say. I listened to the books this time. Next time I’ll read them with my eyes. Luckily, I have a one-volume Kindle edition that includes all four books.

Ferrante made me think about my life as a whole. She also makes me think about aging. And she has quite a lot to say about the relationship between men and women. Her novel might be the perfect illustration as to why we don’t have free will. Whether or not it becomes a classic in future centuries, it is worth reading and contemplating now. It gives us lot to meditate on.

JWH