By James Wallace Harris, Thursday, May 7, 2015

If you live long enough you can watch science fiction evolve. Most fans automatically assume that it’s the advancement of science that spoils older science fiction, but I disagree. “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” by Roger Zelazny is downright silly when it comes to science, but I still love the hell out of that story. It’s my contention that writing dates older science fiction, and not the science.

I just finished reading The Three-Body Problem by Liu Cixin, a sophisticated 21st century science fiction novel from China. Joshua Rothman at The New Yorker called Cixin “China’s Arthur C. Clarke.” I’ve read others who have given Cixin that tag too. Clarke wrote some exciting science fiction back in the 20th century, but The Three-Body Problem storytelling dwarfs anything Clarke wrote. Clarke wasn’t much of a writer, and no stylist at all. His characters were chess pieces used to fictionally illustrate his scientific prophecies. Isaac Asimov wasn’t much better. Heinlein had some writing chops, decent enough in the 1950s, but his later works devolved into solipsistic characters all chatting amongst themselves.

The prose of The Three-Body Problem is refined in ways older science fiction writers never imagined. One way to understand why, is to read another essay by Joshua Rothman, “A Better Way to Think About the Genre Debate.” Rothman uses an idea by the critic Northrop Frye to explain the evolution of fiction over time. Frye believed four genres exist: novel, romance, anatomy and confession. Most science fiction and fantasies are romances. Back in the 19th century before the term science fiction existed, science fiction was called scientific romances. What we call literary, Frye calls novel. Satire, social commentary, philosophy is what goes into anatomy. Confession is autobiographical. The best fiction combines three or four of Frye’s genres. The best of 1950s science fiction combined romance and anatomy. The better 21st century science fiction writers combine novel, romance and anatomy. Ulysses by James Joyce is considered a novel that combines all four forms.

I’m in a 1950s science fiction reading group and we’re discovering that most of the books now considered classics of the genre are rather poorly written. Many, are becoming almost unreadable. But that writing was light-years beyond the science fiction written in the 1920s and 1930s. E. E. “Doc” Smith is painful to read today. I’m worried that my favorite SF books from the 1950s and 1960s will cause young readers today to cringe at its creakiness.

Part of the clunky factor of older science fiction was the poor writing standards of that era. SF editors of the time were not very discerning, and most SF writers wrote quickly to pay bills. Much of the stuff being published in the 1950s came from 1930s and 1940s pulps, and most of the original SF written in the 1950s was slapped together for cheap paperback publishers.

Genre SF tended to focus on the fantastic, the adventure, and were all romance in Frye’s terminology. The trouble is, the fantasies of one generation eventually fail for future generations. To last, a book needs elements of the novel and anatomy by Frye’s definitions. Modern readers will find E. E. “Doc” Smith’s romances silly today. They were pure romance, crudely written. His books might still work for people who enjoy a comic book level of fictional reality, but not for anyone who enjoys the richness of modern fantastic literature.

Goodreads has a nice listing of Best Science Fiction of the 21st Century. At the top of the list is Ready Player One by Ernest Cline. Cline’s exciting and fun story is still not a literary masterpiece by snooty New York literary types, but it is better written and told than most 20th century science fiction. It’s not brilliant like Nineteen Eighty-Four, but then George Orwell wasn’t a genre novelist. Nor does Cline attempt a distinctive style like Samuel R. Delany, J. G. Ballard or Ursula K. Le Guin began doing for SF back in the 1960s. Cline just uses all the good writing practices that modern writers use today. Cline’s novel is fun and speaks to a 21st century audience that remembers the 1980s. I grew up reading Heinlein and Bradbury, writers shaped by their personal experiences of the 1930s and 1940s. Since science fiction tends to be about the future, younger writers are both more savvy about the future, and better trained as writers. They have decades of better novels to study, and they probably graduated from writer workshops like Clarion, or even attend MFA programs.

The exciting aspects of The Three-Body Problem still involve science fictional concepts that have been around since the 19th century, but with new 21st century twists. Just being able to integrate computer networks, the world wide web and computer games into a story gives 21st century science fiction a huge advantage over 20th century science fiction. But I don’t think that’s why Cixin novel is better. His plot is elegantly complex. His characters, although not great by modern literary standards, are far more engaging than what we encountered in most 20th century science fiction. But most of all, he knows how to weave far more information into his fiction without doing infodumps. Older writers often stopped their story to just narrate information they wanted their readers to know. Newer writers know how to paint the background while keeping the story going.

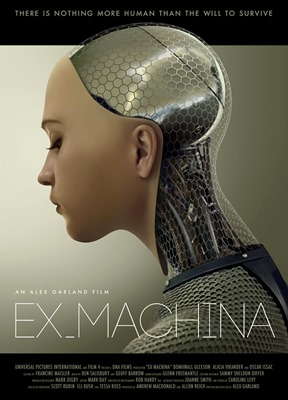

Certainly the Ex Machina robot Ava beats the hell out of Robbie the Robot from Forbidden Planet in both looks and AI mind power. But if you watch the old movie today it creaks. Ex Machina deals with the complexity of artificial intelligence so adroitly that it’s narrative creates a thrilling fictional mystery that even people who have no interest in AI can engage. That was also true for The Imitation Game. Good modern writers can take even the most abstract subject and make it into a compelling story.

It’s surprising how quickly old science fiction develops a patina of quaintness. And for any theme within science fiction, we can see evolutionary development over time. The Sparrow by Mary Doria Russell from 1996 is far more sophisticated at exploring religion and first contact than 1958’s A Case of Conscience by James Blish. More than that, her story is told with far more skill. I expect the next science fiction writer to take a swing at the subject will supplant the other two for a couple decades. And that’s the nature of writing science fiction. We’ve been rewriting the old science fiction ideas since H. G. Wells. New writers have to top old writers. If they don’t, readers will just keep reading the old favorites. Sure science advances, but writing seems to be advancing faster. Otherwise, how could we keep telling alien invasion stories over and over?

Sometimes an old book is just as good or better than a modern equivalent exploring the same theme. Station Eleven is beautiful written, but it doesn’t have the insight into after the apocalypse that Earth Abides revealed to readers in 1949. Both are great novels. And here’s the case for young people to read older novels. Not everything from the past suffers literary decay. Earth Abides can still take on a recent heavy-weight like The Road by Cormac McCarthy. George R. Stewart wasn’t writing from inside the SF genre. And many of the powerful science fiction books that survive from that era turn out to be written by non-genre writers. Two other examples are On the Beach by Neville Shute and Alas, Babylon by Pat Frank. Fifty years from now, future readers will probably be reading The Time Travel’s Wife by Auddrey Niffenneggar rather than any time travel stories from Asimov’s Science Fiction or Analog.

I believe most of the old classic science fiction from the 20th century that’s still in print is because of nostalgic rereading. Baby boomers and millennials push their favorite books onto their children and grand children, and keep them in print. Very few great science fiction novels from mid-20th century remain relevant today. A story like Earth Abides by George R. Stewart still works because a world-wide plague that kills off 99.99% of the population can still happen. But 1950s interplanetary adventures and galactic empires just seem silly today, like a Buck Rodgers serial did to me in the 1960s.

Post Hubble Space Telescope astronomy has made the cosmos light up in IMAX Technicolor so old science fiction seems like old black and white movies. Yet, that’s not the reason why those old novels are becoming forgotten. It’s the writing. Not the science. I’m not sure any of the nine novels selected by the Library of America as the best of 1950s science fiction will survive. My friend Mike claims The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester is just as fresh today as it was in the 1950s. That’s because of Bester’s skill at writing. In the last few years I’ve reread A Case of Conscience, The Long Tomorrow, Double Star, The Space Merchants and More Than Human, I tried to read Who? and The Big Time. I’m sorry, but these books just don’t stack up to what I’m reading today.

One of the challenges facing older science fiction fans reading modern science fiction is the trend for literary writers to invade our genre. Literary novels are slower in pace and more wordy, so fans of older action oriented pulp fiction can find the newer stories plodding. But I encourage them to try and adapt. One reason why Flowers for Algernon is still loved and read today is because Daniel Keyes was a good writer and introducing literary techniques to the genre fifty years ago.

Every decade or two I’ll reread my favorite science fiction books I grew up reading. Sometimes I find a nostalgic glow of rediscovery and sometimes I find a scary sensation of surprised disbelief that I ever loved this story. Because the words in the books don’t change I have to worry that it’s me that’s gone through some kind of cynical transformation. As teenagers we find books that are easy and exciting to read. We don’t have much life experience or critical wisdom. Most of us at that age read whatever we stumble upon. We can bond and imprint on books that are terrible examples of writing. Then as we grow older, and read widely, we get exposed to better writing and writers. We may love our old raggedy stories, but eventually they become toys we need to put away.

A post that actually justifies the cliché “thought provoking”.

I’m glad you avoided arguing that sf was progressing towards something. Linear progression of art is a fixation that goes back to the general idea, developed by St. Augustine, that history is moving towards something. In the area of science fiction, to name an example, people say space opera has progressed beyond Larry Niven to Charles Stross. (That is an example of the rhetoric. I’m not going to evaluate that particular claim.) Implicit in a remark like that is that there is a growing complexity and sophistication which progresses through time and things must and shall move in that direction.

As you say, the raw ingredient of science in science fiction does change.

But you are suggesting an argument of literary ecology, that there are habitats of prose, Frye’s taxonomy describing them. You seem to argue that, as time progresses, more and more sf stories are vital and adaptable enough to inhabit more and more of Frye’s habitats. Thus the modern reader finds the modern sf story more congenial and artful than the old.

But the literary genome — not just subject matter but all the techniques (exposition, plot structure, level of detailed description, pacing, theme, characterization, person of narrator) of literature — behind a story works along many dimensions. How have all those bits changed in modern literature and has the change really made the fiction more timeless and of better quality?

If Frye describes the habitats a novel can exist in, the culture of readers at a given time is like Earth’s climate — it changes and some literary habitats die out (or get their range restricted) and, by extension, the stories that live there. (Death in the sense of no real cultural interest among people to read them.

But metaphors can lie. But I think your post is useful in thinking about sf moving in clades, an evolutionary process where the old is not supplanted, necessarily, by the new but an additive process too.

At least that’s my half-baked response.

I don’t believe we’re moving towards something, but I do believe we’re throwing out swirls of more complex eddies. We live in a universe ruled by the second law of thermodynamics. Statistically, the whole is heading towards greater disorder, yet, in local areas, swirls of higher order appear. I don’t think there is a reason or cause. Sure, St. Augustine and Teilhard de Chardi would argue against me, but I’m fine with being part of a statistical aberration.

Of course, by this philosophy, sometime in the future, writing will get less orderly, and things will fall apart. And it’s interesting to think of science fiction as a clade moving through time, and even becoming extinct.

Mostly what I liked about your post was an alternative to the “sf is progressing” idea.

Evolution strikes me (and I picked up the notion, in various pieces, from Baird Searles, Norman Spinrad, and John J. Pierce) a useful metaphor for thinking about literary development.

Thermodynamics may work too. Our far future descendants may tell sf tales we regard as low-bandwith, simplisitic, and banal. Or there may be great complexity in the stories but without certain elements. For example, maybe, in the singularity, something will tell stories, but the idea of a confessional story will be contemporaneously impossible since all knowledge is shared.

Or, rather like our Hamlet not being the 16th Century’s Hamlet, they may read our stories and get something a bit different out of them than we do.

Now, that’s a fascinating idea – that citizens of future centuries will read our science fiction and see things in it we never imagined, and maybe even missed what we saw altogether. Sort of like the future thinking Elvis was a great religious prophet. Makes me want to write a story about a kid in the 22nd century who reads 20th century science fiction and imagines something truly wonderful. But for me to write it, I’d have to imagine a black swan.

You mention a lot of your favorites were from your youth, Sci-Fi in my youth was mostly Star Wars (still is). But i did like Bradbury, Phillip K. Dick (through Bladerunner) and Herbert’s Dune, although I only read the first book for some reason. It’s an interesting list of a lot of books I haven’t read yet but I’d like to check out.

A great place to learn about science fiction books is Worlds Without End. It collects all kinds of best of book lists. See https://www.worldswithoutend.com/index.asp

Hi! Here via twitter, and I am a big fan of Walter M. Miller and Ursula LeGuin, and a lesser fan of Ray Bradbury. I think all three wrote literary SF in the 1950s and 1960s, and I happily introduce teens to their work and don’t find it dated at all.

I will add that I’m very much looking forward to reading “The Three Body Problem”. May I ask – what did you think of Weir’s “The Martian”? I enjoyed it enormously – thought it a strong story with loveable characters. But I wouldn’t claim that it’s literature. By that criterion, it may not have the enduring value of the other works you mention.

Oh – in addition to Bradbury, some of my young SF and fantasy fans have gotten into Jules Verne. You don’t mention him as being superseded, either.

I reread The Martian Chronicles recently, and it does hold up very well for the most part. Many in our 1950s SF Reading Challenge have been impressed with it too. I’m glad your students still find it worthy. But I am curious to their reaction to A Canticle for Leibowitz, if that’s the story you’re assigning them. Because it’s a fix-up novel, I wonder if it holds up as a novel.

I found The Martian riveting. The writing was nothing fancy but great storytelling. It’s an exceptional reading experience, sort of like Gravity was at the movies. Like you, I don’t know if they will still work with readers decades in the future.

I’ve been meaning to start rereading Jules Verne. I haven’t read any of his books since the 1960s. I did buy an audio book edition of The Mysterious Island recently because of fond memories of reading it in the 7th grade in 1963. I have reread Wells and Mary Shelley and their stuff does hold up well. I’m currently listening to The Last Man by Mary Shelley.

Lately, I’m always surprised when my friends who don’t normally read science fiction, discover a novel like Station Eleven and really get into it. I wonder if science fiction wouldn’t be more popular if there were more well written best sellers that deal with science fictional subjects.

Oh, I work in a public library, and I don’t assign books to anyone! I just recommend them. What is a fix-up novel? “Liebowitz” is still one of my favorite books, and I should be hearing back about it from a couple of teenage boys. Then I’ll know what the modern generation thinks of it.

As I think I said in my original post, I pretty much loved “The Martian”, too, but I don’t know how well it will hold up according to your criteria.

Thanks for your response!

A fix-up novel is one that is composed short stories/novelettes/novellas that were published earlier and separately. The Foundation Trilogy is a set of separately published stories tied together by theme. Many of the classic science fiction “novels” of the 1950s were fix-ups. A Canticle for Leibowitz is based on three stories. The trouble with fix-ups is they usually don’t have a whole unified plot, and often the characters change. I’ve always liked A Canticle for Leibowitz but have always been partial to the first story.

Here’s Wikipedia’s take on the fix-up http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fix-up

Be sure and let us know what your young patrons think of the book.

How much of this is just taste, Jim? How much just changing popular styles? And it’s not just science fiction, is it? Don’t people tend to think that modern books are better written and that older books are quaint, no matter when you ask that question? Won’t the books you admire today seem quaint to future readers?

I didn’t read science fiction as a child, but I was always reading old books. I enjoyed them, but they did seem quaint. They weren’t written to the modern style of that time. Of course, ‘modern’ books back then seem quaint to us these days. So what makes you think that modern books now won’t seem just as quaint to future readers?

True, some books hold up better than others, but you and I probably wouldn’t agree on which books those are. After all, we tend to have different tastes in reading. You think Mary Shelley holds up? I couldn’t even force myself to finish Frankenstein. Different tastes.

I do think that writing has improved over time, but it’s hard to separate that from the simple fact that I’m living now. So, naturally I’d think that writing in current styles and to current tastes is better.

Also, I find that science does date some science fiction. It’s hard to get past vacuum tubes in spaceships, for example. But generally speaking, I can overlook outdated science and old-fashioned writing a lot easier than I can past cultural assumptions (racism, sexism, colonialism, etc.).

For me, that’s what really dates fiction.

Bill, you bring up so many things to explore. Sure, it’s a matter of taste. That’s why so many us baby boomers are still reading the classic SF from the 1950s – we acquired that taste growing up. Since I’ve immersed myself in 19th literary, I’ve acquired the taste, so Mary Shelley prose is pleasing to my ears. Younger readers can develop a taste for older science fiction, even creaky stuff like Doc Smith, but it’s not common.

And you’re also right, that cultural changes and political correctness is a huge factor in turning off people to older books. You’re very science oriented, but you read science fiction – which usually abuses science. I think that makes you forgiving of the older science fiction. Your tastes are quite varied, but among your favorites is Lois McMaster Bujold. She’s a very good storyteller. My guess is you read her because of her writing ability, and not what she has to say about science.

But how many stories do we read at Classic Science Fiction book club that we enjoy but have horribly outdated science and technology? A good story will make us very forgiving of vacuum tube space ships.

People in the future will find most books from the 2010s quaint someday. Writing is always evolving. Most people find Shakespeare’s writing very hard to parse. Part of that’s because the language has changed, but part of that is style. Plus word spellings and meanings have changed, and he alludes to thousands of things our education hasn’t prepared us to understand. Yet, people still love his work because of the storytelling.

Who knows, maybe a hundred years from now Doc Smith’s prose will inspire some movement that enjoys his style as some kind of delicious classic sci-fi kitsch.

We read science fiction for the fiction and not the science. The better the fiction, the greater the chance the story will entertain readers in the future.

Am I ‘science oriented,’ Jim? I’m not a scientist and I’ve had very little formal education in the sciences. But maybe I am. Still, science fiction isn’t science. It’s fiction. If you want science, you’re not going to read fiction.

Does science fiction ‘abuse’ science? I don’t see how. As Mary points out, the science in science fiction is normally a thought-experiment. It doesn’t even have to be science, although in our technological world, it’s science which creates change, and science fiction speculates on change.

Thus, there’s a good reason why it’s called ‘science’ fiction, even though there may be no science in the story at all. It’s a subset of speculative fiction, but it’s not even possible to draw a clear line between science fiction and fantasy.

So, yeah, I agree with you, though I think there are multiple ways in which science fiction can feel dated. And in every one of those ways, the feeling will be different for each individual reader, since fiction is entirely subjective.

Sorry – one more thought, if you don’t mind me butting in, Jim and billgarthright! You say, “We read science fiction for the fiction and not the science”. True – but, to illustrate from another genre, Tolkien (another of my writing heroes, who’s certainly read today!) said that speculative fiction was the purest sort of “subcreation”, and that it would therefore always find readers. The “science” in SF can be a sort of thought-experiment: what if there were a planet where no one was divided by gender? What if we blew up the world in the 1960s, and culture got preserved by a bunch of Benedictine monks? What if a young man found out how to create life? – and so on. I think thought experiments like these, which deal with the human condition, may well lead to stories that endure.

Very true Mary, and an excellent point. That’s what I love best about science fiction over other genres – the fact that it speculates about all kinds of possibilities. But the very best speculation comes through beautiful storytelling. When the author paints the background in fine, realistic detail, it makes us see the possibilities, and then we feel things through the characters way of living in that world.

A fascinating article. There is a lot of schlock in the 50s, and a lot of strictly mechanical stories. There is the beginning of transcendence, though. I’m glad you picked up on the Keyes.

I’d be very interested to see what you think of the stories I’m reviewing…

I assume you mean at http://galacticjourney.org/

I like your project of reviewing old issues of SF magazines. I read your review of Brain Wave, my favorite Poul Anderson story.

I’m not sure I agree at all since my personal experience is largely at odds with the theory presented here.

I don’t have a problem reading/re-reading the classics, nor even many of the proto classics. (Let’s talk masochism here: a few months back I re-read Ralph 124C41+. For the 2.5th time). Did I recognize it as being ‘clunky’? Sure. But I also recognized that it was a progenitor of the genre, Gernsback trying his best to provide an exemplar for the kind of fiction he was looking for. And I had no trouble getting into it, appreciating the speculation, proto world-building or feeling a sense of wonder.

You mentioned Robbie vs the Ex Machina robot. While it is probably true that SF is not DELIBERATELY progressive or evolutionary, surely we recognize that the ideas build upon prior knowledge and experience. There surely is some Robbie in Ex Machina.

More so: To arrive at the ex machina AI, Robbie, and the B5 Robot, and Asimov’s R. Daneel Olivaw, and Binder’s Adam Link, and Fondly Fahrenheit, Smith’s Underpeople, and Collosus, and Skynet, even Jone’s Professor Jameson were ‘necessary’. If those prior articulations hadn’t been in the ouevre, Ex Machina would certainly have been different.

And how does this theory account for the thriving, modern day ‘pulp’ market? Are authors and readers deliberately writing/reading bad, style – less re-hashes, because what? They can’t handle ‘modern’ literary styles? They like bad writing? They’re stuck in a nostalgia groove?

No, I think there’s a couple of things going on. First – the older works had a distinct style and a different focus to their art, Older ‘classics’ focused their efforts on discovering what our species might ‘do’ and how to do it. While more modern SF focuses on ‘who we are’ and ‘what we might become’. Along with that, I believe that style and presentation were used (by good writers, let’s leave hacks out if the discussion entirely) in service to the goal of illustrating what we might do. Space limitations (pulp mags) also constrained style. Why spend words on characterization when it didn’t matter? Good guys, bad guys, got it, move on with the adventure please. And (this isn’t popular) they also relied more on the reader’s sense of wonder than most do now (particularly in film, but it is creeping into literature as well). Read one pulp and you had a good idea of what the interior of a spaceship was like, no need to go all expositoray on us. Somewhere there were controls, somewhere a viewport, somewhere an airlock. And probably a ladder leading to other decks. (Close your eyes, imagine it. I’m pretty sure is resembles the preceding, or the interior of an Apollo command module…)

Second, what about sense of wonder and willing suspension of disbelief? I find it very hard to understand how a sophisticated (experienced, well read) SF reader has difficulty reading older works, either because of stylistic issues or because of dated science. Chances are such a reader has no trouble reading older non-genre works, many of which may have the same issues. I’ve no trouble getting past computers that use tape, for example – that’s the way it is in that universe. Mine is different and isn’t that part of the fun? Style? Like many baby-boomers, I grew up on the entire then history if SF. 1920s thru 60s SF was on the shelf and I read it all and enjoyed most of it. And still do…except for this modern ‘literary’ stuff that thinks it needs to ‘tell’ me everything….

While it is probably true that SF is not DELIBERATELY progressive or evolutionary, surely we recognize that the ideas build upon prior knowledge and experience.

Good point, Steve. I remember reading Michael Crichton’s Sphere (1987) with complete disgust, because it seemed like he’d never read any previous science fiction novels. At the very least, he ignored speculation made by countless previous authors, which made his own story seem laughably clueless.

Still, this progress – not in science, necessarily, but in ideas – is going to make earlier science fiction seem dated, don’t you think? Of course, it will affect different readers in different ways. Fiction is inherently subjective, and we all have different tastes.

You make a good point when it comes to the art of writing, too. Now, I know very little about art, but I do know that ‘primitive’ art has been adopted by many modern artists as a deliberate style.

Many people – artists, too – have seen art as advancing from those primitive beginnings. Certainly, we’ve seen artists become more skilled in scale and proportion, among other things. But is art ‘primitive’ anymore when it’s a deliberate intent to abandon such things?

As I say, I know nothing about art. But I doubt if we’d call modern art deliberately created in an earlier style as ‘dated.’ And literature is art.

To me, there seems to be no particular reason why a modern author couldn’t write in an earlier style,… deliberately. (Indeed, I know it’s been done.) Of course, our appreciation of that would vary. As I say, fiction is inherently subjective, and we all have different tastes. There is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ when it comes to fiction.

That last part isn’t really true. In film, I have a major issue with being “shown” everything, rather than being allowed to participate by using my own imagination. I’m convinced that if someone were to re-make Forbidden Planet, we’d see the following: an entirely different Star Cruiser C57D – one that wasn’t saucer shaped and all kinds of protrusions and pods, turrets, bubbles and whatnots sticking out all over it. Altaira’s zoo wouldn’t just consist of a tiger and a deer – we’d see her gamboling about with a whole menagerie; when ‘Cookie’ gets his load of whiskey, we’d see Robbie constructing an entire distillery; The monster from the Id would ALWAYS be visible; our tour of the Krell city would take up a full 45 minutes as we explore every single level; those giant machines doing incomprehensible things would be explained in detail (this is the fribulator complex that regulates the small aerating creatures – similar to our earthworms – in the soil); at the end when the planet blows up, we wouldn’t see it through a polarized screen as a flash of light on the character’s faces, we’d be out in space, the explosions would roll on and on and the ship would get hit with debris….

There’s plenty of “literary” quality new SF literature that doesn’t do this, but I am concerned that for every, say Three Body Problem or Ancillary Justice, we’re getting ten “show me and explain everything” stories because a good part of the audience is coming to the literature through film and television and games, and the focus there is on eye candy, not the inner mind.

Does anyone remember the first time they read Asimov’s NIghtfall? (Not the novel with Silverberg, the original short.) Ok, the name’s were silly (but there was a convention of number-names at the time and once you got used to it, it was really no more jarring than strange-sounding alien names; I think it took writers until the sixties to get to the “your species can’t pronounce it, so call me X”).

Do you remember trying to imagine what the multi-sunned sky looked like? Do you remember realizing that the thing everyone was so afraid of was the night sky you saw all the time, and how twisty your thoughts got trying to imagine that night sky thru the lens of the character’s mindset?

All of that took place off the page.

Don’t get me wrong. I still love the old science fiction stories. I recently bought a Blu-ray edition of The Forbidden Planet. And I can remember when I first read “Nightfall” by Isaac Asimov. Of course, it helps I was twelve at the time.

If “Nightfall” had never been written and someone wrote it today I’m not sure just how different it would be. What if it was written by Ted Chiang? Or even yet, Alice Munro? Short stories are impressionist by their very nature, so I’m not sure how literary a modern version would be. I guess what we need to ask is: Are there stories being published today that have the same impact and elegant feel?

The writing style would be different, but would the sense of wonder feel about the same?

You and I are too old and experienced with decades of science fiction reading to know. We need a bunch of middle school kids to tell us what stories blew them away with a far out science fictional concept.

But in our experiment, we should give “Nightfall” to a bunch of twelve year old kids and see how it works on them. Will they object to the writing, or only react to the sense of wonder.

Steve, aren’t you a special case? You publish Amazing Stories, so you have a special love for that era. There are always some new science fiction readers who do love the really old stuff. They just develop a taste for pulp fiction. And we don’t have to associate dated with bad, although many people do. And most modern science fiction stories are still action-oriented with little characterization and descriptive narrative.

There are readers who still love Skylark of Space or Captain America, but I think most people who read space adventure stories today will prefer Old Man’s War by John Scalzi or Leviathan Wakes by James S. A. Corey.

Let’s not assume dated equals bad but reflects changing styles. Steve, don’t you think if you were given stories from different decades from the SF magazines, you could guess their age, and maybe even which magazine they came from? Even at Amazing, Gernsback edited stories from the 1920s feel different from Palmer’s in the 1940s, and Cele Goldsmith in the 1960s and Ted White in the 1970s. Didn’t F&SF, Galaxy and Astounding in the 1950s all have different flavors to you?

Sense of wonder endures across all styles and ages, but I’m afraid, dated styles can keep some readers from getting into the story. Popular culture is always changing, and the generations change with it.

My point is writing dates a story more than science. For some readers, that’s not a condemnation, just a subtle aspect, like detecting flavors in wine. The science does date science fiction. We generally know that inhabitable Mars and Venus exist in stories before Mariner 4 flew by Mars.

Science fiction readers have to be much more sophisticated today. Writers have to base their stories on if not fact, at least plausibility or possibility. If a writer predicts that one day everybody will have a hot robot girlfriend, he’d better tell me how we are supposed to pay for it.

James, Bruce.

James – yes, I currently edit Amazing, but as you know we publish very little fiction and, with one or two excpetions, what we have published has been contemporary sf/fantasy/horror written by contemporary authors.

The word ‘dated’ in the context we’re discussing comes across as a negative to me. You may not intend it that way, but it is how I perceive it. And thus my previous response (which was not meant to be argumentative so much as expository).

Herein lies my rub with this basic argument of datedness: which style is more dated in actual language and years – SF from the Smith/Campbell/Edmonton super-science years (1930s) or any of Shakespeare’s plays or sonnets?

The answer is obvious. Yet we continue to laud Mr. S as one of the greatest authors in the English language of all time, teach classes in ‘how’ to read him (some of the usage is so dated that unless you get a history lesson, you are lost, won’t understand the double/triple entendre), frequrntly are presented with ‘updates’ by exoerimental theatre companies (and film…Forbidden Planet) yet we dismiss works less than 100 years old that are arguably more inventive (at least for their era), deal with subjects far-surpassing much of what S concerned himself with.

I’m not arguing that Asimov was “as good a writer as William Shakespeare” – certainly not (bu:t was Twain? Or Faulkner, or Hemmingway?). What I am arguing is that the generally acknowledged “problem” with golden age/classic/antique SF is more than just an issue of language or science. There’s something else also going on, not that I can put my finger on it. Perhaps its that societal concerns have shifted so much that much of it no longer resonates. it may be that most readers have seen the ideas and concepts in later iterations so many times already that it really isn’t anything new or different or interesting enough. (Which I believe is a large part of it).

I don’t really expect a ‘kid’ who was exposed to Halo to get excited by Ringworld. I do expect someone who is “into” science fiction literature to read it, appreciate it, understand that historically it is one of the seminal Big Dumb Objects tales, and to at least acknowledge, if not appreciate Niven’s touch with aliens and with getting the reader deeply involved with the logic puzzles he plays with.

I expect intelligent, experienced readers to realize what era a work was written in – and not get upset when scientists discover a new “ray” that causes or solves (or both!) Their problems. (Unless of course it was written sometime in the past 50 years or so).

So this ‘dated’ writing thing is not the whole story, I don’t think.

Bruce, true enough. I think you can pretty much count on that being the intent of the author for anything written after October, 1939. {at least in Astounding) and for just about everything from about 1955 on. But the question of plausibility has to be asked in terms of the knowledge at the time of writing, not at the time of reading.

For most people, dated does mean something negative. I know lots of people that don’t like old movies, old music and old television shows. They are dated to them. Then again, I know lots of people who prefer old movies, old music and old television shows. But dated also implies something is past its expiration date.

Science fiction is a very popular concept now, but most kids like movie science fiction. There are plenty of young people that read science fiction, but I’d guess most of them like whatever is new and popular with their friends. But there are some fans that dig into the past, and get into the history of science fiction, like the study of literature. Even though I was born in the 1950s, I love movies from the 1930s. Most of my friends won’t watch those old movies with me. They are too dated for them. I can understand that.

I’m currently reading The Last Man by Mary Shelley. It’s very dated, from the 1820s. I like it, but I don’t expect most science fiction fans would, not even fans who claims they like old science fiction, and mean the 1950s.

Asimov wasn’t a good writer in terms of literary qualities, but he was an amazing writer of science fiction. Accepting that he was a bad literary writer doesn’t say anything about his ability to entertain science fiction readers.

Goodness didn’t this spark the discussion. Did you see story about old radio sci-fi series x minus one in nyt magazine last Sunday? A slightly different perspective.

Thanks Linda, I had not seen that piece. To help other people read it, here’s the link http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/10/magazine/letter-of-recommendation-x-minus-one.html?_r=0 . This makes me want to go listen to X Minus One.

Loved your blog James ❤ very well-written. Science fiction is one of the most remarkable genres there is. It gives people a good grasp of what the future might bring.