by James Wallace Harris, Monday, March 25, 2019

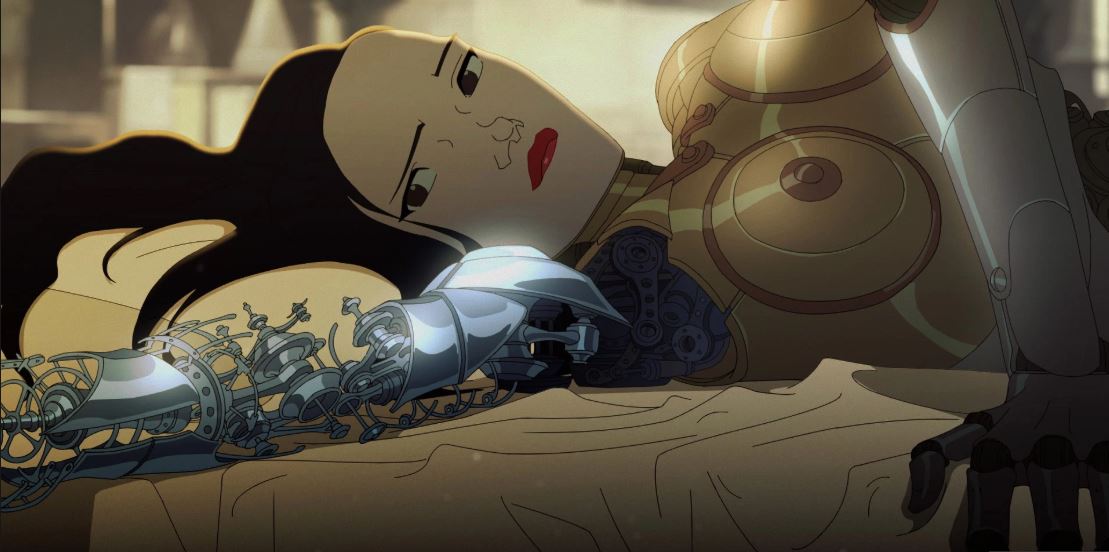

Love, Death + Robots showed up on Netflix recently. It has all the hallmarks of mature entertainment – full frontal nudity, sex acts of various kinds, gory violence, and the kind of words you don’t hear on broadcast TV or in movies intended for younger audiences. There’s one problem, the maturity level of the stories is on the young adult end of the spectrum. 13-year-olds will be all over this series when it should be rated R or higher.

When I was in high school I had two science fiction reading buddies, Connell and Kurshner. One day Kurshner’s mom told us almost in passing, “All that science fiction you’re reading is so childish. One day you’ll outgrow it.” All three of us defended our belief in science fiction, but Mrs. Kurshner was adamant. That really bugged us.

Over the decades I’d occasionally read essays by literary writers attacking science fiction as crude fiction for adolescents. I vaguely remember John Updike caused a furor in fandom with an essay in The New Yorker or Harpers that outraged the genre. I wish I could track that essay down, but can’t. Needless to say, at 67 I’m also starting to wonder if science fiction is mostly for the young, or young at heart.

I enjoyed the 18 short mostly animated films in the Love, Death + Robots collection, but I have to admit they mostly appealed to the teenage boy in me, and not the adult. Nudity, sex, violence, and profanity doesn’t equate with maturity. But what does? I’ve known many science fiction fans that think adult literary works are equal to boredom.

So what are the qualities that make science fiction mature? I struggled this morning to think of science fiction novels that I’d consider adult oriented. The first that came to mind was Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell. Orwell died before the concept of science fiction became common, but I’m pretty sure he never would have considered himself a science fiction writer even though he used the tricks of our trade. Margaret Atwood doesn’t consider herself a science fiction writer even though books like The Handmaid’s Tale are both science fiction and mature literature. Other mature SF novels I can think of are The Road by Cormac McCarthy, Earth Abides by George R. Stewart, and Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro. These are all novels that use science fiction techniques to tell their story but were written by literary writers.

Of course, I could be howling at the moon for no reason. Most television and movies are aimed at the young. Except for Masterpiece on PBS and a few independent films, I seldom get to enjoy stories aimed at people my own age. Which brings me back to the question: What makes for mature fiction? And it isn’t content that we want to censor from the young. If we’re honest, nudity, sex, violence, and profanity are at the core of our teenage thoughts.

Mature works of fiction are those that explore reality. Youth is inherently fantasy oriented. The reason why we’re offered so little adult fiction is that we don’t want to grow up and face reality. The world is full of reality-based problems. We want fiction that helps us forget those problems. Getting old is real. We want to think young.

Love, Death + Robots appeals to our arrested development.

I’m currently reading and reviewing the 38 science fiction stories in The Very Best of the Best edited by Gardner Dozois. I’m writing one essay for each story to discuss both the story and the nature of science fiction in general. I’ve finished 10 stories so far, and one common aspect I’m seeing is a rejection of reality. These stories represent what Dozois believes is the best short science fiction published from 2002-2017. On the whole, the stories are far more mature than those in Love, Death + Robots, but that’s mainly due to their sophistication of storytelling, and not philosophy. At the heart of each story is a wish that reality was different. Those wishes are expressed in incredibly creative ways, which is the ultimate aspect of science fiction. But hoping the world could be different is not mature.

Science fiction has always been closer to comic books than Tolstoy, Woolf, or even Dickens. And now that many popular movies are based on comic books, and the whole video game industry looks like filmed comic books, comic book mentality is spreading. The science fiction in Love, Death + Robots is much closer to its comic book ancestry than its science fiction ancestry, even though many of the stories were based on original short stories written by science fiction writers. Some reviewers suggest Love, Death + Robots grew out of shows like Robot Carnival and Heavy Metal. Even though Heavy Metal was considered animation for adults, it’s appeal was rather juvenile.

I know fully well that if Netflix offered a series of 18 animated short science fiction films that dealt with the future in a mature and realistic way it would get damn few viewers. Even when science fiction deals with real-world subjects, it seldom does so in a real way. Maybe it’s unfair to expect a genre to be mature that wants to offer hope to the young. Yet, is its hope honest? Is it a positive message tell the young we can colonize other planets if we destroy the Earth? That we can solve climate change with magical machines. That science can give us super-powers. That if we inject nanobots into our bloodstream we can be 22 again. That don’t worry about death because we’ll download your brain into a clone or computer. Doesn’t science fiction often claim that in time technology will solve all problems in the same way we rationalize to children how Santa Claus could be real?

Actually, none of the stories in Love, Death + Robots offered any hope, just escape and the belief you can sometimes shoot your way out of a bad situation. But only sometimes.

Maybe that’s not entirely true, one story, “Helping Hand” by Claudine Griggs is about a very realistic situation that is solved by logical thinking. Strangely, it’s the only story by a woman writer. A “Cold Equations” kind of story. That’s a classic 1954 short story written by Tom Godwin where the main character has to make a very difficult choice.

My favorite three stories (“When the Yogurt Took Over,” “Alternate Histories” and “Three Robots”) were all based on stories by John Scalzi and have kind of zany humor that provides needed relief from the grimness of the other tales. I actually enjoyed all the short films, but I did tire of the ones that felt inspired by video game violence. Even those films like “Secret War” and “Lucky Thirteen” which aimed for a little more maturity, rose higher than comic books, but only to pulp fiction.

The two films based on Alastair Reynolds stories, “Zima Blue” and “Beyond the Aquilla Rift” seemed to be the most science fictional in a short story way. I especially like “Zima Blue” for its visual art, and the fact the story had an Atomic Age kind of science fiction feel to it. So did the fun “Ice Age” based on a Michael Swanwick story. Mid-Century science fiction is really my favorite SF era. Finally, “Good Hunting” based on a Ken Liu has a very contemporary SF feel because it blends Chinese myths with robots. World SF is a trending wave in the genre now.

I’m still having a hard time pointing to mature short SF, ones that would make great little films like in Love, Death + Robots. Maybe “Good Mountain” by Robert Reed, which I reviewed on my other site. I guess my favorite example might be “The Star Pit” by a very young Samuel R. Delany, which is all about growing up and accepting limitations. Most of the films in Love, Death + Robots were 8-18 minutes. These stories might need 30-60. It would be great if Netflix had an ongoing anthology series of short live-action and animated science fiction because I’d like to see more previously published SF stories presented this way. Oh, I suppose they could add sex, nudity, violence, and profanity to attract the teenagers, but what I’d really want is to move away from the comic book and video game plots, and into best better SF stories we read in the digests and online SF magazines.

JWH

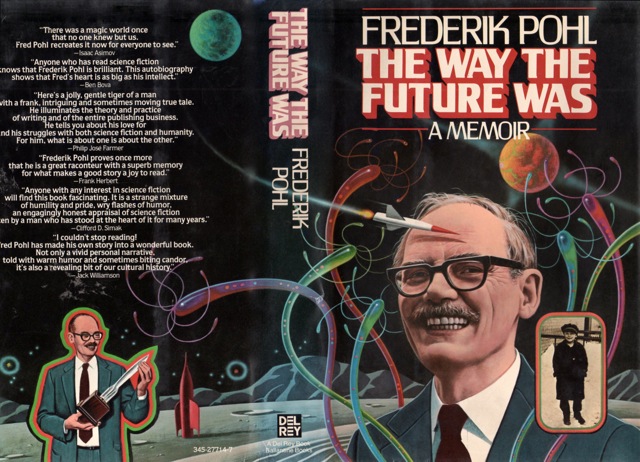

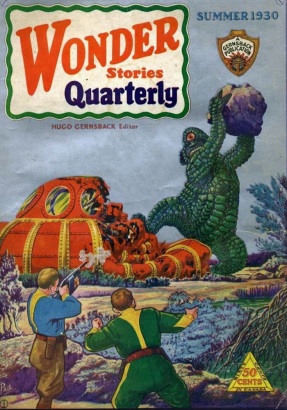

Hugo Gernsback began the science fiction genre by publishing Amazing Stories in April 1926, but soon lost control of the magazine, and started another magazine Science Wonder Stories in June 1929. Astounding Stories of Super-Science began it’s run in January 1930. The earliest science fiction fans, sometimes called First Fandom, all began reading science fiction about this time. Fred Pohl discovered science fiction in the Summer 1930 issue of Wonder Stories Quarterly. Pohl wrote, “I opened it up. The irremediable virus entered my veins.”

Hugo Gernsback began the science fiction genre by publishing Amazing Stories in April 1926, but soon lost control of the magazine, and started another magazine Science Wonder Stories in June 1929. Astounding Stories of Super-Science began it’s run in January 1930. The earliest science fiction fans, sometimes called First Fandom, all began reading science fiction about this time. Fred Pohl discovered science fiction in the Summer 1930 issue of Wonder Stories Quarterly. Pohl wrote, “I opened it up. The irremediable virus entered my veins.”