Marie Kondo, the guru of tidy, preaches, “Discard anything that doesn’t spark joy.” I’ve been buying music CDs for over thirty years and my collection is a huge mess. I definitely don’t love all the albums I own. There’s always the conflict between collecting and playing. Like all hoarders, I tell myself that one day I will want to play this album. Well, I have albums I haven’t played for a quarter century. I bought Marie Kondo’s the life-changing magic of tidying up because she talks about sorting through books. I figured the same approach applied to albums. This issue is further complicated by the fact that nine-five percent of the time when I play music, it’s via Spotify.

Six key issues to consider:

- Does owning compact discs spark great joy?

- Do I find great joy in the high fidelity of compact discs?

- Do I find great joy in the album or the song?

- What sparks the deepest joy in collecting albums?

- How does digital libraries affect the philosophy of tidying up?

- How many albums is too many?

Does owning compact discs spark great joy?

Streaming music services like Spotify offer gigantic music libraries for a low monthly subscription. Why bother keeping my thousand albums when I have instant access to millions? Kondo says we should only own things that bring us joy. Is the physical container of music something that brings us joy? Even though I’ve put the price of a SUV into my music collection, is it still worth keeping? Does the whole collection have sentimental value, or just parts of it?

Kondo tells us “The criterion is, of course, whether or not it gives you a thrill of pleasure when you touch it.” Does a CD have some kind of emotional physical value? Is a favorite song less meaningful to my life if it streams through my Roku rather than plays on my CD player? To be honest, I don’t have any physical attraction to my CDs. I was quite sentimental over my LPs when I bought them back in the 1960s and 1970s, but when I started buying CDs in the 1980s, they never acquired that aura of emotional objects.

If I knew I could always have access to the same music I own through renting I’d get rid of all my CDs. Because I don’t have that assurance, I want to keep all my albums that I treasure. Yet, what do I treasure when its not the physical object? Is it all the songs on an album, or just special ones?

Some albums bring me great joy. Some albums are keys to memories. I need to save those keys.

Compact discs were always too small to enjoy visually, and their booklets were always too hard to read. They succeeded because of convenience and sound quality. Streaming music is even more convenient, but the sound quality isn’t quite the same.

Do I Find Great Joy in the High Fidelity of Compact Discs?

One of the main reasons to keep compact discs is their high fidelity. This only matters when I’m sitting in my den and I’m listening to music in the same way I concentrate on a movie at the theater. Otherwise, 320kbps streaming files are fine. However, there are times when I want as much sonic detail as I can get. The other day I read One Way Out, a history of the Allman Brothers. It inspired me to get out my Allman Brothers albums that I haven’t played in a decade. Once again I was back to listening so intently just to distinguish Duane from Dicky. Listening with intense concentration to every instrument begs to have the fidelity to create a large soundstage that showcases every musician’s performance.

Until Tidal, all subscription services used highly compressed files that have less fidelity than compact discs. And there are other digital formats that offer great fidelity than CDs. Unfortunately they involve buying digital files I’d have to maintain, and that’s a kind of clutter that’s more difficult to manage than physical clutter.

When it comes right down to it, the essential reason to own a compact disc is because I want to have it forever. I don’t want to ever lose access to some songs. Second in importance is to have the highest fidelity possible. I’m going to assume that future streaming will involve higher fidelity. But I can’t assume Spotify or its competitors will always have a license to stream my most cherished memories.

Do I Find Great Joy in the Album or the Song?

Most of the albums I bought in my life were because of one song. Few albums spark joy in their entirety. Blonde on Blonde, even though it’s a double album, in one I embrace in its wholeness. It’s a complete work of art. As I study what Kondo is trying to teach me, a philosophy of how to live with objects and always keep them in their place, I push myself to understand why I love certain things. When dealing with albums and books, I’m really judging them as containers of art. The art is priceless, but the containers are just that.

Compact discs are storage bins for music. Spotify is another kind of storage bin. Contemplating this tidying-up issue, I realize there are two kinds of music containers – one which I never want to lose no matter what. That involves keeping the album. Songs, on the other hand, which appear in various other kinds of containers – best of albums, anthologies, singles, soundtracks, etc, are much easier to rent through Spotify.

I’ve always loved the 1965 hit single “Eve of Destruction” by Barry McGuire. Yet, I’ve never been without a copy. I’ve had it on 45, LP and CD in various collections. Now I stream it. And I believe it will always be on streaming. I recently owned the original LP album it appeared on, but it was an old beat up copy I got for 50 cents. When I cleaned out all my LPs I gave it to the library because it was the only song on the album I liked. There was no sentimental reason to be attached to the LP.

When I ask myself if a CD/LP sparks joy, it can’t be just for one song – unless that song is nowhere else. “Song for Our Ancestors” by the Steve Miller Band, off their Sailor album, is the only song that sparks Kondo joy. Actually, it’s the only Steve Miller Band song that unlocks a memory. It’s not available on streaming. I have to save that CD if I want to always have access to “Song for Our Ancestors.” If that song had been on a Best of Steve Miller Band album, I wouldn’t save Sailor.

This also makes me ask: Should I save Best Of albums? Hits are the one type of song I can depend on Spotify to always have. Hit songs are constantly repackaged, anthologized and put on soundtracks. Hits are frequently heard on radio and Pandora.

What Is The Deepest Joy In Collecting Albums?

I love to visit someone’s home and look through their shelves of books, music and movies. When we collect, we create the fingerprint of our pop culture soul. The albums I want to save are the ones that define me. Not because I want my friends to see them, even thought I dig when they do, but because I want to define myself to me. My shelves of books, movies and albums should be a mirror for self-examination. Growing up, I tried to define myself by the size of my library, but now the only thing that matters is what each work of art reveals about myself. When I play an album I love it’s an act of meditation.

How Does Digital Libraries Affect Tidying Up?

It’s quite easy to part with albums that I know are on Spotify. Do I learn the same lesson from giving them away if I knew I couldn’t listen to them again online? Because of Spotify, Netflix, Amazon Prime, Audible, Kindle and Scribd I now buy fewer books, albums and movies. My pile of digital clutter grows and grows, but it’s out of sight. Can I still derive the psychological rewards of being tidy that Kondo promises if I have an invisible pile of possession in the cloud?

If every book, movie and album was on Scribd, Netflix and Spotify, I could just own nothing, and just think of all those works in someone else’s library. Then it would be Scribd, Netflix and Spotify’s problem for keeping things tidy. I could reduce my home library to a chair and iPad for Zen like simplicity. I could paint the walls white, wear white clothes, and sit in my room reading and listening to music in my tidy personal Shangri-La.

How Many Albums Is Too Many?

After a lifetime of buying thousands of albums, I realized I no longer listen to most of them. When I retired I had about 1,600 CDs and hundreds of LPs. Two years of culling and I’m down to about 900 CDs and 50 LPs. Soon, I’ll be down to less than 500 CDs and no LPs. Yet, I expect my collection to keep shrinking. 500 is still too many. Kondo tells her clients to have a goal in mind. My goal is to have a library of albums I absolutely adore. I can’t even remember what I own. That’s not special. It’s like having more children than you can remember their names.

When I first retired, I realized I could have become a record collector because I was buying used LPs and CDs five or ten at a time. However, the convenience of Spotify has spoiled me. I only get out a CD when I’m in the mood to thoroughly focus on the music. And that tends to be for albums I really love – the ones I want to play straight through. What I’ve learned from fifty years of buying music is most of what I bought hasn’t been memorable.

I had a friend, John Williamson, who died back in the 1990s. John was crazy about music. Before he died, he told me he had gotten down to listening to just Benny Goodman and Duane Allman. My sphere of music is shrinking too. To maintain a vitality for life you have to maintain as many interests as you can. Yet, getting old means learning to live with less, and as we age, the amount we can handle dwindles. Two years from now I might still love 300 albums. If I live to 80, I might just cherish a 100. I believe John died young because he got down to only two musicians. I wonder who he was hearing when he left this world? Benny or Duane.

I’ve been playing Blonde on Blonde for half a century. Will it be playing when I fade out of existence?

Some of my younger friends fear this trend. They see losing interest in things once loved as a bad sign, but I see a positive angle in my declining years. As my record collection shrinks I get to know what’s left better. It’s a musical tontine.

Music is like a drug that energizes me. If I’m feeling down, music can lift me up. Music hyperlinks me to people and events. Music anchors my memories. It’s terribly sad when I play an album I bought long ago and can’t remember why, when or where I bought it, nor remember any of the songs. That’s an area of my garden I neglected and now it’s patchy with dirt and weeds. What’s best is to let another album expand into that space. I think shrinking my collection as pruning.

Using Spotify has taken away the incentive to buy new CDs, but I do on rare occasions. I still discover new artists on Spotify, and when I find one I want to keep forever, I buy their CD. For instance I’ve bought the last three CDs of Sarah Jaffe. I don’t think I will ever get so old that I’ll stop adding albums to the library of music that defines me.

Nor, have I found all the replacement CDs from the past LPs I loved. The last LP replacement I bought was Shady Grove by Quicksilver Messenger Service – an album I’ve been waiting for a decade to come to subscription music. I finally gave up and bought it. I bought it the first time in 1970 as an LP. It had just one song I loved, “Edward, (The Mad Shirt Grinder)” I couldn’t get on Spotify.

Another positive purpose in culling albums is it gives me purposeful activity. Being retired, and having all my time free, requires a knack for keeping busy. I should be outside tending to a real garden, but I’m not that kind of guy. I’d rather tend a sound garden, or make up metaphors about one.

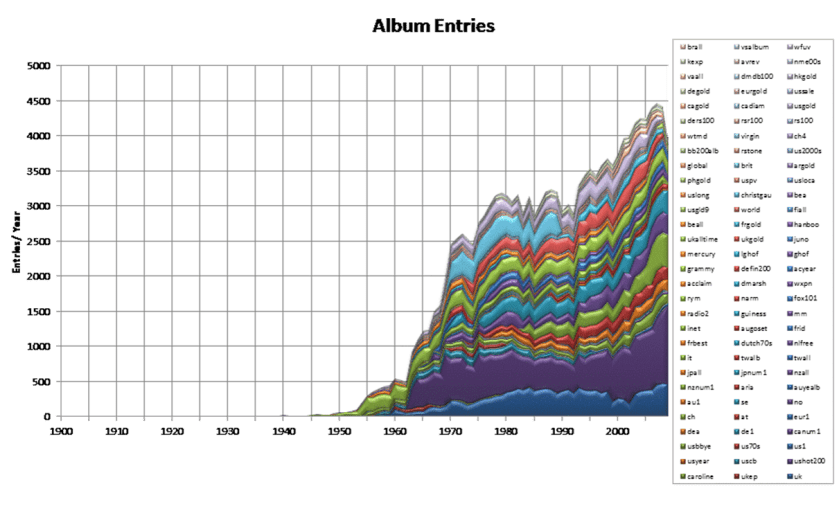

Since 1965 I figured I’ve bought between 2,500 and 3000 albums in my life. That’s about 2,600 weeks ago, so call it an album a week on average. Although for many years, I averaged four albums a week. I started out with LPs and 45s, but eventually bought mostly CDs. The way music is delivered has changed a lot in my lifetime. I mainly skipped the cassette and 8-track phase, but I did dip into SACDs and iTunes singles. I pretty much went from CDs to streaming music, which is where I’m at now. I could go to Spotify for all my listening, but I still want to own a album collection. I’ve had one since I was thirteen, so I can’t stop now.

In the heart of Marie Kondo’s book is the lesson to save what you cherish. I’m on a journey to discovery those albums I truly love most – and defining that library sparks joy.

JWH