by James Wallace Harris, Friday, January 12, 2018

I’m listening to the AmazonClassics audiobook edition of Journey to the Center of the Earth by Jules Verne, a novel originally published in France in 1864, and first translated into English in 1871. The translation I read was by F. A. Malleson, from 1877, and is considered a pretty good translation. Verne suffered from many bad translations, often ruining his reputation in the English speaking world. The story is impressively narrated by Derek Perkins. His voice perfectly matches this 19th adventure tale. This audiobook sounds more thrilling and real than most of the silly movie and television productions I’ve seen.

However, I have one problem with Verne’s story. It’s not very believable. Of course, it’s well over a century-and-a-half since Verne imagined it, and science has progressed a great deal, but was it even believable in his day? I wish I had an AI robot that could read and understand fiction and nonfiction. I want to talk to it like Alexa but it would be much smarter. I want my AI mind to crawl across the web and answer questions for me. Google is so goddamn stupid that it drives me crazy. I searched for [19th-century reviews of “journey to the center of the earth”] but it only brought up modern reviews of recent book editions and movie versions. I thought my query was quite explicit. If Google is such a leader in AI, why can’t it understand my query? Don’t you get tired of all the crap Google searches return?

I want to build an AI mind that I could input texts of all the science fiction stories and novels from the 19th and 20th centuries and have it analyze those works by correlating that content with information found on the internet. Journey to the Center of the Earth was originally published in a magazine for boys. I’ve love to find diaries, journals, essays, and books by 19th-century readers who read Journey to the Center of the Earth when it came out and to know their reactions. Verne adds a good deal of science from his day into his story to make it sound plausible, but was it?

Hollow Earth theories and stories go back much further than Verne. Were its proponents and speculating on real possibilities and taken seriously? Or, were they the UFO nutters of their day? I get the feeling that the concept of dinosaurs had inflamed 19th-century imaginations and Verne used his story to speculate how dinosaurs could still exist. He was doing the same thing that Doyle’s The Lost World and Crichton’s Jurassic Park did, creating a theory to present live dinosaurs. I have many theories about the evolution of science fiction, and having an AI collaborator could really help.

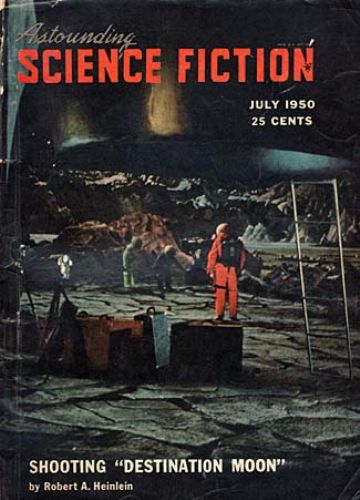

I’d love to build an AI robot that I could chat with me about science fiction. I picture talking my digital companion like Mannie did with Mike in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress (1965) by Robert A. Heinlein. I imagine creating my AI friend like the AI machines in When HARLIE Was One (1972) by David Gerrold or Galatea 2.2 (1995) by Richard Powers, where Harlie and Helen came into consciousness by interacting with a human mentor. I fantasize talking with this AI and collaborating on articles about the history of science fiction. And what if it woke up and became conscious?

Computer scientists are building AI machines using machine learning to do all kinds of things today. If they can master games like Chess, Jeopardy, Go, and old Atari 2600 games, or analyze MRIs and X-rays for cancer, why couldn’t they learn everything to know about science fiction.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about learning ML (machine language) using Python. I’ve been daydreaming about building a machine after reading (“Deep Confusion: Misadventures in Building a Deep Learning Machine,” “The $1700 great Deep Learning box: Assembly, setup and benchmarks,” and “Build a super fast deep learning machine for under $1,000“) or just paying for a hosting service like Paperspace. There’s a new edition of Python Machine Learning: Machine Learning and Deep Learning with Python, scikit-learn, and TensorFlow by Raschka and Mirjalili that could get me started, or Hands-On Machine Learning with Scikit-Learn and TensorFlow: Concepts, Tools, and Techniques to Build Intelligent Systems by Aurélien Géron.

Of course, I doubt if I could ever program such a fantastic AI machine or even learn the basics of ML at my age. I’ve been watching a series of videos from Google Developers on Machine Learning Recipes. I’ve also been reading about Natural Language Processing with Python, a book I bought years ago when this idea first came to me. The concepts aren’t hard, but it would be just the first steps on a journey of ten thousand miles. I’m not sure I have the concentration power or memory space anymore. I’m probably too old and too feeble minded to do it, but that doesn’t mean some youngster couldn’t.

I’m quite envious and jealous that young people today can choose this kind of work for their career. I programmed databases during my work years, and that was fun enough, but imagine getting to develop robots, AI minds, and machine learning? What an exciting time to be a programmer.

JWH

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume One is probably the most loved science fiction anthology of all time and comes in #1 at Goodreads list of

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame Volume One is probably the most loved science fiction anthology of all time and comes in #1 at Goodreads list of