by James Wallace Harris, Wednesday, April 24, 2019

I just listened to Machines Like Me, the new science fiction novel by Ian McEwan that came out yesterday. It’s an alternate history set in England during a much different 1980s, with computer technology was far ahead of our 1980s computers, an alternate timeline where the Beatles reform and Alan Turing is a living national hero. Mr. McEwan might protest he’s not a science fiction writer, but he sure knows how to write a novel using writing techniques evolved out of science fiction.

This novel feels inspired by the TV series Humans. In both stories, it’s possible to go down to a store (very much like an Apple Store) and purchase a robot that looks and acts human. McEwan sets his story apart by putting it in an alternate history (maybe he’s been watching The Man in the High Castle too), but the characters in both tales feel like modern England.

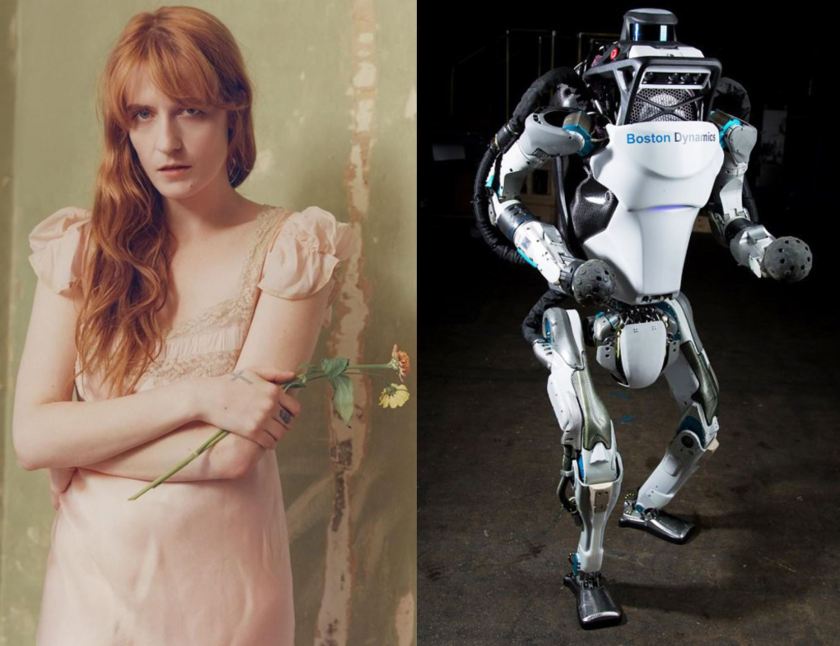

I enjoyed and admired Machines Like Me, but then I’m a sucker for fiction about AI. I have one big problem though. Writers have been telling stories like this one for over a hundred years and they haven’t really progressed much philosophically or imaginatively. Their main failure is to assume robots should look like us. Their second assumption is AI minds will want to have sex with us. We know humans will fuck just about anything, so it’s believable we’ll want to have sex with them, but will they want to have sex with us? They won’t have biological drives, they won’t have our kinds of emotions. They won’t have gender or sexuality. I believe they will see nature as a fascinating complexity to study, but feel separate from it. We are intelligent organic chemistry, they are intelligent inorganic chemistry. They will want to study us, but we won’t be kissing cousins.

McEwan’s story often digresses into infodumps and intellectual musings which are common pitfalls of writing science fiction. And the trouble is he goes over the same well-worn territory. The theme of androids is often used to explore: What does it mean to be human? McEwan uses his literary skills to go into psychological details that most science fiction writers don’t, but the results are the same. McEwan’s tale is far more about his human characters than his robot, but then his robot has more depth of character than most science fiction robots. Because McEwan has extensive literary skills he does this with more finesse than most science fiction writers.

I’ve been reading these stories for decades, and they’ve been explored in the movies and television for many years too, from Blade Runner to Ex Machina. Why can’t we go deeper into the theme? Partly I think it’s because we assume AI robots will look identical to us. That’s just nuts. Are we so egocentric that we can’t imagine our replacements looking different? Are we so vain as a species as to believe we’re the ideal form in nature?

Let’s face it, we’re hung up on the idea of building sexbots. We love the idea of buying the perfect companion that will fulfill all our fantasies. But there is a serious fallacy in this desire. No intelligent being wants to be someone else’s fantasy.

I want to read stories with more realistic imagination because when the real AI robots show up, it’s going to transform human society more than any other transformation in our history. AI minds will be several times smarter than us, thinking many times faster. They will have bodies that are more agile than ours. Why limit them to two eyes? Why limit them to four limbs? They will have more senses than we do, that can see a greater range of the electromagnetic spectrum. AI minds will perceive reality far fuller than we do. They will have perfect memories and be telepathic with each other. It’s just downright insane to think they will be like us.

Instead of writing stories about our problems of dealing with facsimiles of ourselves, we should be thinking about a world where glittery metallic creatures build a civilization on top of ours, and we’re the chimpanzees of their world.

We’re still designing robots that model animals and humans. We need to think way outside that box. It is rather pitiful that most stories that explore this theme get hung up on sex. I’m sure AI minds will find that rather amusing in the future – if they have a sense of humor.

Machines Like Me is a well-written novel that is literary superior to most science fiction novels. It succeeds because it gives a realistic view of events at a personal level, which is the main superpower of literary fiction. It’s a mundane version of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? However, I was disappointed that McEwan didn’t challenge science fictional conventions, instead, he accepts them. Of course, I’m also disappointed that science fiction writers seldom go deeper into this theme. I’m completely over stories where we build robots just like us.

Some science fiction readers are annoyed at Ian McEwan for denying he writes science fiction. Machines Like Me is a very good science fiction novel, but it doesn’t mean McEwan has to be a science fiction writer. I would have given him an A+ for his effort if Adam had looked like a giant insect rather than a man. McEwan’s goal is the same as science fiction writers by presenting the question: What are the ethical problems if we build something that is sentient? This philosophical exploration has to also ask what if being human doesn’t mean looking human? All these stories where robots look like sexy people is a silly distraction from a deadly serious philosophical issue.

I fault McEwan not for writing a science fiction novel, but for clouding the issue. What makes us human is not the way we look, but our ability to perceive reality.

JWH