by James Wallace Harris, 10/10/22

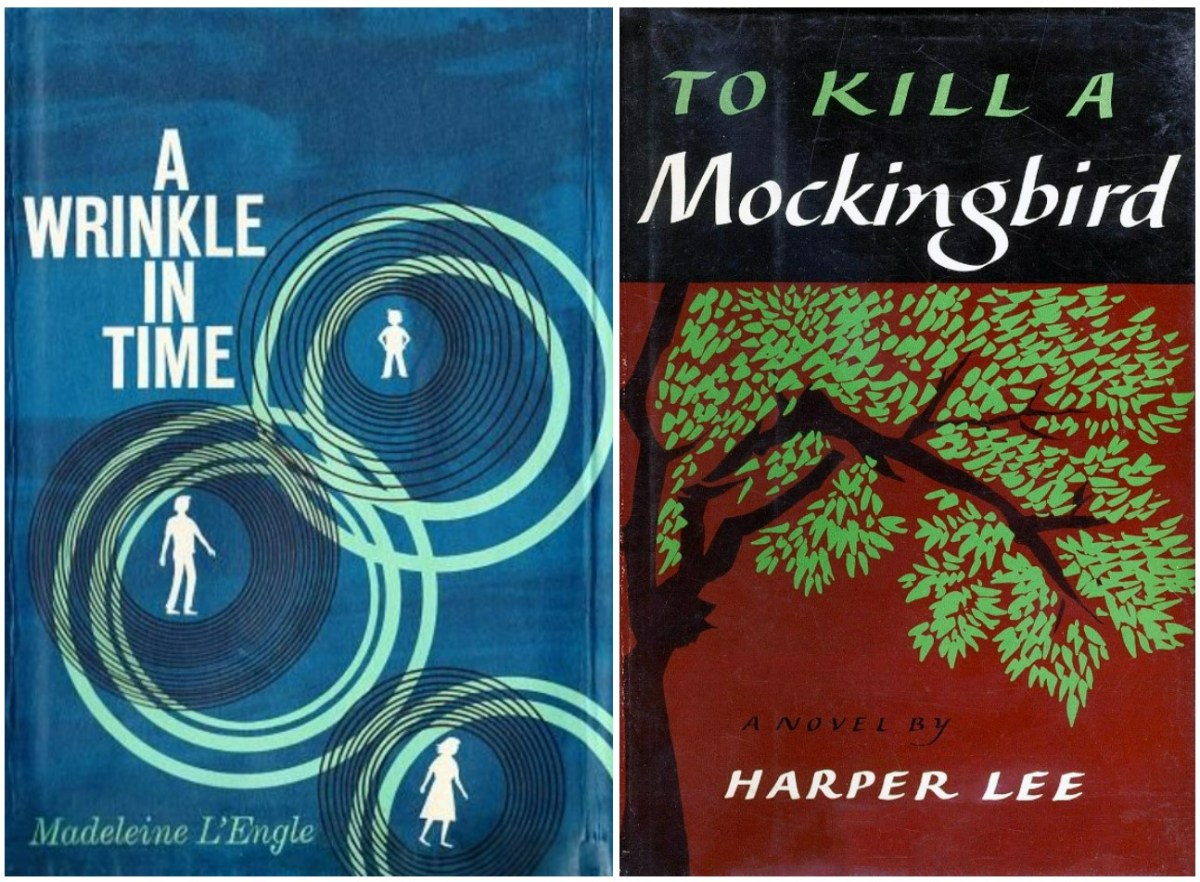

In 1962, when I was in the 6th grade, my teacher Mrs. Saunders would read to the class after lunch. The book I remember from that year is A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L’Engle. I found it so exciting that I went to the school library and checked out a copy so I could read it faster than 30 minutes a day. At the time, I didn’t know the novel was science fiction, or that the story belong in a category of fiction. But looking back, I see Mrs. Saunders had put me on the road to becoming a science fiction fan.

Yesterday, I wondered if Mrs. Saunders’s influence on my life would have been different if she had read To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee instead? Would I have become a different kind of bookworm? Instead of being fascinated with space and time travel, would I have become interested in social justice and equality? I did come to care about those issues later on in the 1960s as the decade progressed, but could I have been made aware of them sooner by reading the right book?

Even though I mostly read science fiction, I do read some serious literature. I was an English major in college. I know when they come out, The Best American Short Stories 2022 will have far deeper, more mature, better-written stories than The Year’s Best Science Fiction Vol. 3: The Saga Anthology of Science Fiction 2022. Yet, the odds are I’ll probably buy and read the science fiction anthology.

In eighth grade, my English teacher required us to read three books each six-week grading period and raised our earned grade by one letter if we read five. She had an approved reading list. That’s how I discovered Heinlein. She gave me the chance to read science fiction and non-fiction, and I took it. What if I had read A Tree Grows in Brooklyn or The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank instead? Would I have matured sooner? Would I have been more conscious of the real world?

What if in 1965 I read The Painted Bird by Jerzy Kosiński instead of Stranger in a Strange Land? Would I have become a different person? Or, did I read what I read because I was an immature kid that could only handle the immaturity of science fiction? I tend to think it’s the latter because I know serious literature is far superior to science fiction now and I still seldom choose to read it.

I believe I read science fiction then and now to escape from the real world. I read nonfiction as a kid and as an adult to learn about the world. However, I do wonder how I would have been different if I had gotten addicted to serious literature as a kid.

If I had a time machine and could go back to talk to my younger self I would tell him to read To Kill a Mockingbird. I’d say, “Kid, stop daydreaming about going to the Moon and Mars. Other people will do it, but not you. And if you could, you wouldn’t like it. Our personality isn’t suited for space travel. Spend more time with people and less time with books, and when you read a book, make sure it helps to know more about people.”

I’m pretty sure my younger self wouldn’t listen. People don’t take advice. Not even from our future selves.

For all I know, Mrs. Saunders may have read To Kill a Mockingbird to us and I just ignored it. She read us several books that year, and A Wrinkle in Time is the only one I remember.

JWH

Does science fiction really ignore the real world? There is plenty of SF that deals with social issues other space travel, ranging from environmental issues to political freedom, and realist, everyday literature that doesn’t deal much with them.

Yes and no. A comic book can deal with a serious issue. There’s a difference in how an issue is handled. A lot of modern SF stories think they are dealing with a vital issue, but they usually don’t deal with the subject in depth. If you compare literary writers who have written science fiction, such as Orwell, Atwood, Ishiguro, etc. to how science fiction writers handle the same subject, you’ll see what I mean.

Which science fiction novels would you point to as being deep and heavy about reality?

I think some genre SF–Asimov, Heinlein, Bradbury–has deal with political repression in as much depth–or at least, with as much eloquence–as Orwell and Atwood. Heinlein’s early story “The Long Watch” struck me as a strongly anti-fascist story. Asimov’s story “The Winds of Change” (written in the late seventies) is a vivid evocation of religious fundamentalism. Harry Harrison’s 1966 novel Make Room! Make Room! is a powerful portrayal of environmental crisis and its effects on ordinary people.

Science fiction writers often deal with an idea, but seldom convey it on a personal level. You seldom feel their characters experience the ideas like Offred in The Handmaid’s Tale or Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four. I did feel it with Ish in Earth Abides, but George R. Stewart wasn’t a genre writer. I do remember Make Room! Make Room! having an impact because of the ideas, but I don’t remember the character. I should reread it.

I thought the first chapter of The Ministry of the Future had tremendous impact and depth, but the rest of the novel was too cerebral.

Understood, although to me the experiences of the characters in the stories I mentioned were as vivid as the ideas.

Do you remember their names?

I remember the trio in “Make Room! Make Room!”—Solomon Kahn, Andy Rusch, and his girlfriend Shirl (I don’t recall her last name offhand). I don’t recall offhand the name of the young bomb officer in “The Long Watch” who dies in his resistance to Colonel Tower’s attempted military coup. But I remember vividly the actions and attitudes of all these characters, including several of their statements.

I need to reread those stories.

I think the best way I can illustrate the difference between literary fiction and science fiction is to suggest you read a volume of The Best American Short Stories.

“I think the best way I can illustrate the difference between literary fiction and science fiction is to suggest you read a volume of The Best American Short Stories.”

I’ve read a lot of realist, literary fiction—however one describes it—-and I understand the difference you’re referring to. I just think that SF isn’t completely escapist, and often deals with real-world issues, with vividly realized characters and situations, even if not the fully rounded, three-dimensional characters of “mainstream” fiction.

I see what you mean. That’s true, some science fiction is paying attention to reality. And the intent of the story is to get the reader to think about something real. For example, Heinlein’s story “Solution Unsatisfactory,” about dirty bombs. He was saying we’ll have to work like crazy to keep irresponsible counties from having that technology.

My problem is the story still has to work at an emotionally satisfying level while still be an engaging and satisfying story.

I think Heinlein did that with “Requiem.” But other stories from that time aren’t as tightly constructed. I need to reread “The Long Watch.” Wasn’t it written later?

I just looked up “The Long Watch” (in my copy of the omnibus collection The Past Through Tomorrow) and it was published in 1948, nine years after “Requiem.” I also found the name of the young protagonist of “The Long Watch,” Johnny Dalquist.

That was when Heinlein was aiming higher, for the slicks. I expect he wrote a lot tighter then. In my rereading project, I’m only up to 1940, so it will be awhile before I get to it.

The credit note reads, “Copyright 1948 by The American Legion.” I guess it was published in their publication. It does have a military, patriotic aura, albeit in the context of resistance to fascism.

I think Sputnik , when I was seven, set me up for science fiction more than any particular book. Not so much the launch, but the change in the environment. Science suddenly became acceptable.

Sputnik was long before my time–I was born in 1964–but I gather that not only science but also SF gradually became more acceptable after that. I grew up in the seventies, and while I haven’t known many people throughout my life who share my liking for SF, I also haven’t known many people who deride me for reading that Buck Rogers stuff, etc. which I gather was more common in earlier years.

Doug, I don’t remember Sputnik. I turned 6 the month after it launched and I wasn’t even watching the news then. But I followed all the Mercury launches and you’re right, the space program is probably the main reason I took to science fiction in 1962.

I enjoy hearing about everyone’s experiences. Strangely enough, I was never as interested in the real-life space program (NASA, etc.) as I was in reading and watching SF, including SF about space travel, etc. I always related to it as a branch of fantastic literature, parallel to fantasy, supernatural, etc.

You’re not alone. When I was young I thought all science fiction fans were fans of the space program too. But I’ve since discovered that’s far from true.

At times I was mildly interested in the space program–although I eventually developed reservations about the whole idea–but I was really an SF nerd rather than a NASA nerd.

I remember Sputnik well and being my elder age, I also remember a great little 30 minute TV show, probably in the 50s, called Science Fiction Theater. I have always liked science and sci-fi..

I was a big Star Trek fan, especially NG, and it makes me sort of sad, as I doubt whether much, if any, of those ideals and stories ever come true now.

Despite it’s appearance, I still think that science fiction is not really a genre. It was created as a genre by Hugo Gernsback, that to my knowledge, was restricted by a formulistic rigidity that could only have happened in the pulp magazines, at least until more radical authors like Robert Heinlein came along. I think that rather than being an homogeneous form of writing, it contains a variety of differing groups of authors, that fall into categories of basically straight science fiction, such as Robert Heinlein writes, the borderline science fantasy, plainer fantasy that authors like Michael Moorcock write, and the broader spectrum of speculative fiction, that more complex and visionary authors write. This isn’t meant to be a paradigm, because they can all overlap with tropes common to one of the others, but it’s definitely a group of divergent authors sharing a common mode that makes it more than a genre.

Olaf Stapledon wrote science fiction under general literature during the reign of the pulp magazines. Anna Kavan’s “Ice” was first published outside of science fiction before Brian Aldiss advised American SF house Doubleday to publish it. I wonder what the response to it would have been if it had happened the other way around? I think that Margaret Attwood’s “The Handmaid’s Tale” is what would have been a banal science fiction dystopian novel if it had of been published within the genre. George Orwell’s “Nineteen Eighty-Four” is a great literary novel that could probably have been a great science fiction novel. There’s “Frankenstein” of course, that was written before there was a science fiction genre, and Bram Stoker’s “Dracula”, both Gothic novels sharing a similar background before there were genres. Not all science fiction can’t definitely be concentrated at any one point in time and space, and nor perhaps can general literature.

I think you chose the literature you liked rather than be swayed by any popular consensus, but you weren’t limited to either realm. I’m perplexed by your attitude to SF, which you like and respect. Without it, you wouldn’t have read great authors like Philip K. Dick. I like to think I read what I like and is good.

s

I agree Richard that science fiction is entirely to varied to be pigeonholed by one label. Unfortunately, it is.

I love science fiction. My problem is I start reading so many stories that disappoint me. Like Sturgeon said, 95% of everything is crud. Now that I’m old I wish I hadn’t put up with so many of those cruddy stories. I wish I had spent the time on better stories and read more widely outside the genre. However I’m conditioned to read science fiction and its hard to switch now.

I just regret not reading more stuff from outside the genre. When I did read To Kill a Mockingbird I realized what I was missing. I just wondered today if I read it sooner would that have changed things.

We all have our regrets. I’ve read many stories and novels I didn’t care for (Philip Jose Farmer’s To Your Scattered Bodies Go, Poul Anderson’s Tau Zero), but I don’t regret having read them, since there’s no other way of discovering works that you do like. Perhaps my only regret in this regard is struggling through Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men until I was four-fifths of the way through, and not bailing out sooner.

My larger regret regarding SF is different from yours. When I got out of my teens, for some reason I forgot about genre SFF until I rediscovered it in my early thirties, and I’ve been very gradually catching up ever since. I sometimes regret all the reading of genre SFF I missed in the intervening period, even though during those years I discovered other worthwhile reading, such as the works of various Latin American writers, Yiddish and Hebrew writers, etc. (much of it with elements of the fantastic, magic realism, etc.), and I’m glad I discovered that as well. Nevertheless, coming back to genre SFF has been like coming home.

| didn’t like a substantial amount of SF, particularly that done by the more famous authors. It was the less famous but great authors, like Philip K. Dick, that turned me away from SF and in the direction of general fiction. There’s so much I haven’t read there, as there is in SF, but there’s good and bad in both realms. I wish I hadn’t read “The Handmaid’s Tale”, which is dreary like a fair number of mainstream books, but I’m glad I read SF for the very good stuff.

Sadly, I fear Mrs. Saunders would not be allowed to read or recommend To Kill a Mockingbird in many of our states today. It’s being banned in numerous states and school districts. And, even in the more liberal states, she would probably have to deal with parents who only want their children to hear their version of history. Maybe your reading would have ranged more widely if you had been exposed to different books earlier, but you still became a voracious reader and, clearly, an open-minded deep thinker. That’s saying a lot these days….

What books are kids assigned to read these days?

Now, that’s a great question. I have no idea what kids are reading in school. I don’t have kids and all the neighbor kids are now in college or beyond. I’d love to know what’s required and recommended reading these days. Hope they’re being challenged and exposed to lots of new ideas….

I found these lists:

6th grade – I’ve read just 4 of them:

https://www.differentiatedteaching.com/6th-grade-books/

8th grade – I’ve read 8 of them:

https://k-12readinglist.com/reading-lists-for-middle-school-children/reading-list-for-8th-grade-students-age-13-14/

Thanks for finding those lists. I have to confess I can recall reading only one from the first list and four from the second. Looks like there is some good stuff in there … and To Kill a Mockingbird should definitely be among them.

Many of the older recommended books are now banned, which is absurd…I saw a complete list and it’s unbelievable.

My grade school teacher back in the 50s would do the same, read from a book of her choice that she felt was fit for our age group. The only one I remember her reading was something from Mark Twain, which I had read years earlier since I learned to read at 6 years old and had already taken on Twain and many others. I loved ‘ To Kill A Mockingbird’ and read it many times over the years. It didn’t make me a social justice warrior, although it did give me a boost of interest into what I had already witnessed growing up in the south. Lee’s south, was realistic of how it was in the 30s, and that carried on into the 50s, 60s, and in some parts of the deep south, still exist today. We needed more than two books from her.

I think the books Mrs. Saunders read us where just ones she picked. I never felt like they were part of the curriculum. But then, maybe that’s how she wanted to sneak them in on us.

I grew up mainly in Miami, but I went to part of the 3rd grade in Marks, Mississippi, and part of the 10th in Charleston, Mississippi. Now that was an education. I also lived in South Carolina twice as a kid. But also Pennsylvania and New Jersey. All those schools in all those states were an education.

This according to the American Library Assoc.

Many books that were historically banned ended up becoming literary classics that are still taught in modern classrooms. Accordingly to the ALA, frequently banned classics include:

“To Kill a Mockingbird,” by Harper Lee

“The Catcher in the Rye,” by JD Salinger

“The Grapes of Wrath,” by John Steinbeck

“The Color Purple,” by Alice Walker

“1984,” by George Orwell

“Brave New World,” by Aldous Huxley

“Native Son,” by Richard Wright

“Slaughterhouse-Five,” by Kurt Vonnegut

“A Separate Peace,” by John Knowles

“The Lord of the Flies,” by William Golding

I’m curious who banned or challenged Orwell’s 1984, and on what grounds. Of course, the real reasons may be different from the given ones.

Finally, BannedLibrary.com’s entry on 1984, a bulleted list, explained:

1950 – Banned and burned in communist Russia under Stalin and USSR, ownership meant possible arrest for its anti-communist views. Allowed back in country after editing in 1990.

1981 – Jackson County, Florida – challenged for being pro-communist and contained “explicit sexual content.”

Wrenshall, Minnesota – teacher was fired for refusing to remove it from reading list (unconfirmed)

2009-10 – Amazon deleted it and Animal Farm from users kindles sparking controversy. Amazon found that the “copies” deleted had been published illegally from an independent publisher that had ignored copyright laws (1984 is under copyright until 2020) and the money spent was refunded. This was more of a recall to protect copyright than a ban or censorship case.

2017 – Idaho – book is under scrutiny after being challenged by a Jefferson County parent for having “violent, sexually charged language.”

Many thanks for all this background, maryplumbago! I shake my head at the obtuseness of many of these censors and would-be censors, although maybe obtuseness and censorship go hand in hand. Could anyone really describe 1984 as “pro-communist”? To characterize Brave New World as “anti-religion” and “anti-family” is equally curious, since two aspects of the totalitarian society which Huxley portrays (and deplores) are suppression of traditional religion and the traditional family. Maybe these censors confuse portrayal of an imagined world with advocating it.

(However, Brave New World was first published in 1932, so its banning in Ireland and Australia must have been a bit later)

P.S. I also wonder this about Brave New World. The reason I wonder about these two novels is that they are in some sense more respectable than the other books on the list, being mainly anti-totalitarian, and in the case of 1984, anti-Stalinist.

Brave New World was rated #3 on the American Library Association’s 2010 list of most challenged books, but history of controversy extends back to its publication. The novel was first banned in Ireland in 1931 for anti-religion, anti-family, and blasphemous content. Australia quickly followed by censoring the book in the same year. In the United States, there were eight separate accounts of censorship in states including Maryland, Missouri, Oklahoma, California, Alabama, Texas, Indiana, and Delaware, all of which occurred in US public schools. Brave New World continues to challenged in public schools for obscenity and vulgarity, and being therefore inappropriate for children. A father of a student has argued that “the novel’s dystopian setting disallows students from understanding ethical citizenship and morality.”