by James Wallace Harris, 8/12/13

Most bookworms just want to be entertained. They know their tastes are so individualistic that no friend or authority can predict what they will like. However, teachers and literary scholars like to think that certain books should be read, and a tiny fraction of readers are willing to read books because they have a great reputation. We feel reading the classics makes us a better person.

There is no FDA like agency that officially rates books as choice or prime. So, what makes a classic novel? The common assumption is novels that survive the test of time are the real classics. However, you can go on Amazon and order a lot of books from the 19th century that no one considers classics. Some people consider books that are taught in school or college to be the classics. And there is some merit to that, but literary works that get taught are also subject to the whims of pop culture, and English departments.

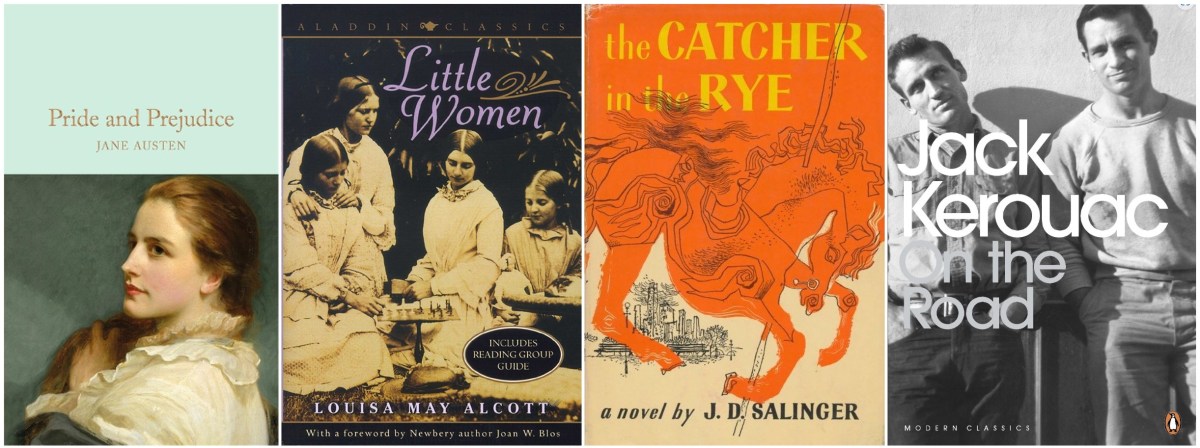

I mention all this, because I read “8 Overrated Literary Classics and 8 Books to Read Instead” by Jeffrey Davies, especially since it throws four of my favorites under the bus: On the Road by Jack Kerouac, Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen, The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger, and Little Women by Louisa May Alcott.

Of course, this is clickbait, but I’ve seen this kind of essay before. A couple other examples are “13 Overrated Literary Classics, and What to Read Instead” by J. W. McCormack and “9 Overrated Classics — And What to Read Instead” by Zoraida Córdova.

I understand why young people rebel and want to overthrow the reading lists of the past, especially a past dominated by white male writers. And sure, sometimes these articles are just giving suggestions as to something different to read. But other times, I do feel the writers just hate the classics they are demoting. I often see On the Road and The Catcher in the Rye listed in these literary rebellions. (A hilarious generational attack on The Catcher in the Rye is the novel King Dork by Frank Portman)

What I would like to propose are rules for this game. If you want to oust a literary classic, you need to provide a proper substitute. All too often, these writers offer alternatives that are just their personal favorites, and usually something from recent decades. Classics have specific qualities that any substitute should have too. They include:

- A snapshot of history – time, place, and subculture

- Innovation in writing style and techniques

- A philosophical or psychological insight

In other words, classic novels offer a view of everyday life in the past, even if it’s inaccurate, slanted, or distorted. That’s why I’m against publishers cleaning up aspects of older novels to make them politically correct for modern woke minds. We need to know both the good and bad about how we were. No censoring or whitewashing the past by substituting novels that agree with your moral and ethical sensibilities.

Classic novels supplement history books to build mental models of the past in our heads. Removing any one of them takes pieces of the puzzle away from the collective images we’re building of our cultural heritage and history.

If you’re serious about offering replacements because you feel an existing classic work doesn’t do the job well enough, then suggest a novel that offers a better view of the same time and setting. One that is more insightful.

The trouble is, doing just this is extremely hard. Readers have spent decades and centuries winnowing out the best novels. You might dislike novels for the views they show, but finding good replacements takes a lot of work and reading.

I would suggest, instead of trying to replace specific classic novels, you offer supplements instead that expand or enhance the classics. For example, The Catcher in the Rye (1951) and On the Road (1957) are about alienated youth in America before the youth rebellion of the 1960s. We need more novels about kids growing up in America in the 1940s and 1950s to expand on the views those two famous classics give. I would suggest Horseman, Pass By and The Last Picture Show by Larry McMurtry and The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath, among others.

The challenge would be to find novels written near the time and setting covered, ones that have been forgotten but are worth resurrecting and remembering. There is something more authentic about novels written by people who lived in the time of the novels as opposed to later novels that are historical fiction.

Few novels are truly contemporary. On the Road was set in the 1940s, but was written in the early 1950s, and published in 1957. It takes a certain number of years to get the perspective and write things down. Breakfast at Tiffany’s was published in 1958, but about 1943. And it’s not the early sixties we see in the film, and neither is the plot or characters. Holly Golightly is a lot closer to Neal Cassidy than most people realize. She is another alienated youth from the 1940s, and another supplement for The Catcher in the Rye.

I understand why young readers dislike older novels. I can understand why they want to promote their favorite stories as classics. But I don’t think it’s an ethical idea to suggest they should replace the older classics, especially with newer novels.

They need to decide which novels from the eras in which they lived paint a worthwhile picture of those times and places, and then promote them as the classics that represent those settings and characters.

If these essay writers need a hook to promote the books they love, please don’t throw the books under the bus that other people love. I’d suggest being straight forward and creating titles like: “The Best Books about Miami in the 1980s.” Or “Novels About People Who Lived Down the Street from Jane Austen.” Or “Characters Who Lived While Jack and Neal Were On the Road.” Or “Novels That Louise May Alcott Read That We Should Read Too.”

JWH

Great article, Jim. Full of wisdom and very good ideas.

I am very interested in bilbiotherapy, but haven’t yet developed the points about its value that I would like to be able to articulate. Reading novels should help us develop our skills of empathy and self understanding as an individual and as a member of the society we are living in.

People get out of a novel what they bring to it, and that is why reading a novel at different points on one’s life cycle engenders new and different perspectives and understandings. So the idea about what “classics” are recommended reading and why might be the idea of when in their age and life situation should they read them?

I have other ideas about this topic as well, but commenting upon your article is not the time and place to share them. However, great essay which as got me thinking.

I didn’t know there was such a thing as bibliotherapy, but it sounds like a great idea. How does it work?

Does it involve opposites? Like if you have a student who is a bully give them a book by a character being bullied? An empathic remedy.

Or would you give them a book with a bully POV character. A homeopathic remedy.

An extension would be to offer students the option to substitute a book the consider of value for a classic. Of course they would have to defent their choice.

I would replace “Moby Dick” with “Gravity’s Rainbow”

I’ve always wanted to read Gravity’s Rainbow but it’s size has scared me off. I have read Moby Dick. I still might get to GR someday.

I am not up to date on what books are covered in schools. I do agree they should not be removed because someone thinks they are not what people want to read. It should not be based on personal taste. There needs to be developed (and maybe there is already), a guideline or chart of attributes a novel should have to be include in school studies. I understand it would be difficult to do because of all the factors to consider, but if students are not interested, they will not get anything out of what they read and may possibly turned off of reading novels altogether. For example, a couple of years ago, I read The Betrothed by Alessandro Manzoni. It was set in the 17th century but published in the 19th century. It is a historical novel during the time of the Black plague in Europe. It was fascinating to me. I drew so many comparisons as we were going through the covid pandemic when I read it. My opinion would be it should be included as recommended reading (maybe it is), but greater minds than mine need to evaluate if it should be included.

Well, you make me want to read The Betrothed. I’d also like to read how Manzoni did his research on the 17th century.

I recommend it.

I agree, Jim. Also, I feel that many of these articles exhorting us not to read this book but read that one instead are just as authoritarian and overbearing as the literary norms they’re supposedly rebelling against. I’d rather check out these various works for myself and see what looks interesting.

considering i’ve yet to make it through MOBY DICK (i’ve tried several times), take my opinion with however many grains of salt you wish, and found more to relate to in the later work of jack kerouac (DOCTOR SAX or BIG SUR) and with the exception of GRAPES OF WRATH and THE LAST PICTURE SHOW have never gone back to any assigned reading for a more mature shot, i can only wonder what they’re pushing as required reading for fourteen to eighteen year olds these days.(hopefully, i can ask my sisters grandkids if i cross paths with them this thanksgiving.) meantime, i’d be interested in hearing who your correspondents have listed in their personal academy of the overrated. ernest hemingway? james joyce? harper lee? richard brautigan? charles dickens? and that’s just literature….

in the interest of full disclosure, i reread THE GREAT GATSBY (which i still think is overrated; better than hemingway,not as intriguing as faulkner) back in 2020. my interest was kindled (no pun intended) after reading UNDER THE RED,WHITE AND BLUE by greil marcus. it’s essentially a one hundred fifty-four page essay on scott fitzgeralds vision of this country, its promise and shortcomings. required reading for every patriotic american.

I’ve read Greil Marcus books on rock, especially Dylan, but not on literary guys. I might read his book on Fitzgerald.

I’ve dabbled in Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and Faulkner. My mother grew up near Faulkner, and I’ve been to his house. I like them all equally. I guess Faulkner is more real to me because my mother’s generation all knew about him and talked about him. People in Mississippi would say they liked his brother John better, who was also a writer.